The Philadelphia Board of Education approved a nearly $4.5 billion preliminary budget on Thursday that officials said isn’t enough to properly fund the district. They also got an earful from frustrated students and teachers.

At a board meeting that lasted more than six hours, members reviewed district presentations and heard from more than two dozen student and community speakers about a variety of problems and concerns. These include over 3,000 student dropouts, rapidly decaying facilities, an inadequate funding formula, and — perhaps most damning of all — a growing number of students who say they don’t feel heard or cared for by district leaders.

“Will you continue to be the detriment of Philadelphia’s students? Or will this be the wake-up call where you pay attention to their wants and needs, their thoughts, feelings, and emotions?” Jeron Williams II, a Central High School student, asked board members.

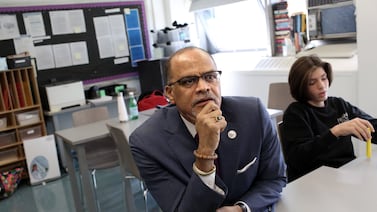

Amid the challenges outlined at Thursday’s meeting, Superintendent Tony Watlington and Chief Financial Officer Michael Herbstman presented a $4.45 billion preliminary budget and accompanying five-year outlook. The board approved the proposed budget 9-0.

That budget doesn’t include capital costs for renovating or rebuilding school facilities, Herbstman cautioned, and a more detailed final budget is scheduled for a vote on May 25.

Still, Watlington and several board members noted more money is needed to address the district’s most pressing concerns. The Education Law Center and Public Interest Law Center estimate “fair funding” in Philadelphia would require an additional $4,976 per student. That would mean an additional $1.1 billion and $318 million annually from the state and city, respectively.

With that kind of money, Watlington said, the district could “update aging facilities” and address asbestos and lead concerns, raise teacher salaries and provide “comprehensive professional learning” opportunities, among other changes.

Watlington and Board of Education President Reginald Streater said the next step will be to aggressively lobby city and state government officials for more funding. They said the school district only controls some 10% of their budget. The remaining 90%, including salary and benefit costs, is in the hands of negotiated contracts and city and state leaders.

Streater said the board and Watlington are having to “rebuild a district that was pulled apart piece by piece,” following decades of funding cuts.

“That’s important for the public to understand the scope,” Streater said. “We’re doing the best we can with what we have.”

Herbstman’s financial outlook for the district in fiscal 2024, which begins July 1, projects a 6.1% increase in revenue, but expenses are projected to increase 6.9%. And after September 2024, Herbstman said, federal COVID relief aid for schools will run out and the district will be facing “a significant deficit.”

“Absent major changes each subsequent year the annual deficit will continue to worsen,” Herbstman said.

Another long-term issue is the state of school infrastructure, which has been the subject of clashes between the district and city officials recently. Oz Hill, the district’s deputy chief operating officer, said that while the district has received 91 nominations for needed facility renovations, “the truth of the matter is we probably can only fund … a fraction of those projects.”

That kind of backlog did not sit well with board Vice President Mallory Fix-Lopez.

“I will be long gone from this earth and our students will still not have libraries, they still will have asbestos in their schools, teachers will still be working in 100 year old buildings … if we don’t get our young people the $1.1 billion they’re constitutionally owed from this state and $318 million from the city level,” she said.

Though the centerpiece of the board’s Thursday agenda was the budget, board members altered the schedule to accommodate a frustrated and rancorous crowd. They demanded board action on issues with the lottery admission system, charter school reform, asbestos in buildings, and what they called poor communication from district leadership.

“You’re killing us,” Kristin Luebbert, a teacher at The U School, told the board Thursday, referring to the unsafe physical condition of schools. “Our building issues have been decades in the making, but now is the time to make a plan to fix them.”

According to a district presentation Thursday, 3,373 students have dropped out of the public school system as of February — on par with last year’s count. The most recent district data shows there are about 197,300 students enrolled in Philadelphia public schools.

That prompted Sophia Roach, the school board’s sitting student representative, to ask what — if anything — the district is doing to bring the dropout rate down.

In response, Watlington did not offer details, but said “we are putting in place supports and processes to better address this issue.” He said he would have to do “a deeper dive” to look into what individual schools are doing to retain and support students.

Carly Sitrin is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Philadelphia. Contact Carly at csitrin@chalkbeat.org.