The issue of charter schools is one of the biggest ongoing debates in Philadelphia and the education landscape nationwide.

On the rise across the U.S. since the 1990s, charters have added fuel to the question of how to allocate school funding and whether parents should have more options for where to send their children.

The influx of charters, which now constitute about a quarter of schools managed by the School District of Philadelphia, has complicated the decision-making process for parents choosing between the public neighborhood schools nearby, magnet public schools with citywide admissions, and tuition-based private schools.

Local policymakers have long sparred over how many charter schools should operate in the district, how oversight of their administration should work, and how they should be funded relative to public schools. The Philadelphia Board of Education has not approved a new charter since 2018, the year it regained authority over the district from the state, which had temporarily taken control of Philly schools.

In partnership with The Logan Center for Urban Investigative Reporting and Chalkbeat Philadelphia, Billy Penn is launching a series examining how charter schools are impacting educational disparities in Philadelphia. We’ll explore how charters are managed, how they stack up against the city’s public schools, how equitable their admissions are, the politics behind their funding, and what the experience of teaching at a charter is like, among other topics.

To kick off, we’ll address 10 key questions about charters and how they differ from other school models.

What are charter schools?

Charter schools are best understood as a hybrid between public and private schools. They receive a good amount of government funding and are held to some of the same operational standards as public schools, but are managed privately. In Pennsylvania, they’re managed by nonprofits.

While exempt from a lot of the Pennsylvania School Code, charters must maintain the same employee criminal history checks, open meetings, health and safety regulations, special education programs, civil rights, and open records as public schools do. Charter schools also have to follow the same statewide assessment system, including administering the PSSAs and the Keystone exams.

Charters must offer core courses (think math, science, and English) that are aligned with state and federal standards, but can design their own curriculums. Charters are also allowed to offer their own electives and academic programs or “tracks,” such as Spanish immersion programs or programming around the arts or sciences.

Of the Philly School District’s nearly 200,000 students for the 2022-23 academic year, about 58% were enrolled in public schools, 33% in charters, 7% in cyber charter schools, and the remainder in alternative schools.

How are charter schools funded?

Charter schools are different from private schools, which receive no public funding and charge each student tuition.

In Pennsylvania, local school districts follow a state formula to send charters a per-student payment from their taxpayer-funded budget. Exactly how much depends on each district’s per-student expense, so it varies widely across the commonwealth.

For non-special education students, the per-student amount allocated to charters in the 2023-24 academic year ranged from about $8,600 in Luzerne County to over $26,500 in Bucks County. Philadelphia falls on the lower side of the scale at about $11,500 per non-special ed student.

The special education expenditure is much higher, usually at least double the per-student amount. In Philadelphia, the district sends charters more than $36,000 per special education student enrolled.

How do charters get started?

To open in Pennsylvania, a nonprofit must first apply to and obtain a charter from its local school board that outlines a set of requirements and standards for the school to operate. (Cyber charter schools obtain their charters directly from the state.) The board must hold at least one public hearing on the application.

If a charter school is rejected during the process, the nonprofit behind it can revise and resubmit the application locally or appeal the decision to a state board composed of the Pennsylvania secretary of education and six members appointed by the governor.

Charters must be renewed by the school district at least once every five years. The local school board can choose to renew the charter for just one year if it has questions about the school’s performance, with the idea that it will use the additional year of academic data to determine whether to renew the charter for longer.

What are the arguments in favor of charters?

Since their inception in Minnesota in 1991 and their arrival in Philadelphia in 1997, charter schools have been a hotly debated topic.

Proponents argue that they improve student success in the long term. They often believe the public school system in place doesn’t serve all students well for various reasons, ranging from systemic inefficiencies to intrinsic biases. Those in favor of charters say their existence creates needed competition between schools, increasing the overall quality of education by forcing schools to innovate in curriculum and approach.

Some charter schools perform exceptionally well; some do not. In 2023, 21 of U.S. News and World Report’s top 100 high schools were charters (none is in Pennsylvania). The list ranks schools based on performance on standardized tests, college preparation, and graduation rates, among other factors.

What are the arguments against?

Opponents of charters believe they harm public schools by funneling money away from an already underfunded public school system to privately administered institutions with less oversight than the district at large.

Past charter school CEOs and other administrators in Philadelphia and elsewhere have been accused of mismanaging or even embezzling millions of dollars in funding.

Opponents also argue that charter admissions can be inequitable due to bias or bad management, or too selective based on the sensitive information an applicant may have to give when applying. For example, in 2012, Philadelphia’s overseer of charters found 18 schools imposed “significant barriers to entry,” with one school requesting a typed book report and proof of citizenship.

A significant proportion of charter schools don’t survive. Nationwide, more than 25% of charters close within five years, and 40% close within 10 years of opening, according to a 2020 analysis by public school advocacy group the Network for Public Education.

Between 2013 and 2020, Philadelphia saw 16 charter schools close, according to the school district. The district currently has 87 charters in operation, versus 217 district-run public schools.

How do charter schools perform versus public schools?

On average across the country, there were “no measurable differences” found between reading or math scores at either the fourth grade or eigth grade level, according to a 2017 U.S. Dept. of Education report.

In Philadelphia recently, there were minimal differences between the lowest state test scores for charters and public schools. In science, about 33% of charter school students scored “below basic” compared to 34% in public schools, according to an analysis of 2022 PSSA data for schools in the district.

In English, about 25% of charter school students scored below basic versus 30% for traditional public schools. Math scores were similar, with roughly 65% of students in both charter and traditional public schools scoring below basic.

Philly charter schools had an average 85% four-year graduation rate in 2021, while traditional public schools had a 75% average graduation rate, according to an analysis of district data.

How do students get into charters?

Charter schools, like all other schools, are legally not allowed to discriminate against race, religion, gender, and other forms of identity. But while any student can enroll in a charter, if more students apply than the school can teach, students are put into a lottery system.

These charter school lotteries are not overseen by the district and have at times faced criticism of discrimination.

Last spring, for example, a top administrator at Philadelphia’s top-rated Franklin Towne Charter School alleged that the lottery was manipulated to keep certain students from being enrolled and that most of the students denied were from predominantly Black ZIP codes. The school district investigated and found enough evidence to recommend the charter be revoked. The Philadelphia School Board voted in August to send Franklin Towne official notice of this, kicking off a process that could take years to resolve.

Who teaches in charter schools?

Pennsylvania law says at least 75% of charter school professional staff must hold appropriate licenses and certification.

Principals, vice principals, or assistant principals at charters must hold administrative certificates. Special education teachers, school nurses, school psychologists, speech and language pathologists, and any positions defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, must also hold appropriate and valid certifications.

Unlike at public schools in Philadelphia, regular teachers at charter schools are not required to be certified.

Charter school teachers can be a part of a union. The Alliance for Charter School Employees in Philly, organized by the PA-AFT, allows individual employees of charter schools to join its union even if other members of the school choose not to.

What are Philadelphia Renaissance Schools?

Back in 2010, Philadelphia School Superintendent Arlene Ackerman launched a “Renaissance Schools Initiative” aimed at improving the lowest-performing public schools by turning them over to charter nonprofits.

These schools became charter schools with one difference: Instead of open enrollment, they are required to continue to serve students in their “catchment areas,” or neighborhoods.

At first, seven district schools were turned over to charter providers, and more were converted under Superintendent William Hite. But since their inception, four of these schools have either closed or been returned to the district as public schools. In the 2023-24 academic year, there were 18 Renaissance charters in operation.

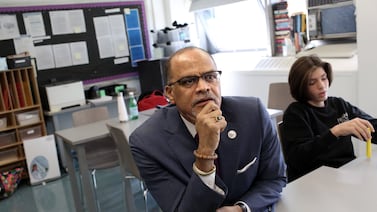

Where does Cherelle Parker stand on charters?

Cherelle Parker, the Democratic nominee for Philadelphia mayor who is heavily favored to win the race to succeed Jim Kenney in November, has been guarded in her comments on the district’s current charter school system. (Philly mayors do not have direct oversight over schools, but do appoint school board members.)

Parker has said she supports “good seats” no matter what kind of school they’re in, “but we can’t get there if there is a battle between charters and traditional public schools,” she told Chalkbeat last spring.

To reduce the criticism that charters suck funding out of the public school system, Parker said she would advocate for state reimbursement to districts for any student that switches from public to charter. This used to exist, but was rolled back in 2011.

“Reinstating this will grow the pot of funds and allow for more opportunity for Philadelphia’s students no matter what type of school they attend,” Parker said.