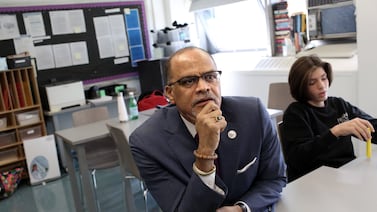

Superintendent William Hite announced Tuesday the launch of an equity coalition, a comprehensive initiative to end racist practices in the Philadelphia School District, with plans to confront issues ranging from selective admissions policies to educators’ implicit bias.

The coalition “is an organized effort to uproot systems of inequity,” Hite said in a briefing for reporters. The initiative will begin with committees made up of educators and other district employees, and it will eventually include parents, students, and community members.

“We are starting this effort with a laser focus on race and racism, because...it is the root to all systems of oppression,” said Sabriya Jubilee, the district’s director of planning who is helping to lead the initiative.

The equity coalition will focus on a wide array of problems, including the racial achievement gap, selective admissions policies, teacher diversity, and the underrepresentation of Black and Latino students in advanced courses. It also will look at issues related to special education students, immigrants and English language learners, gifted programs, and LGBTQ students.

Hite said that this will be a planning year for the coalition and that any policy changes — including in the admissions process for selective schools — will not take place until next school year.

District leaders also announced the creation of an office of equity within the central administration.

Estelle Acquah, the director of special projects, said the district also plans to offer professional development“with an anti-racism focus,” and will enhance curriculum “through the lens of cultural responsiveness.”

“Overall, the coalition will define what equity means within our district and develop a systemwide equity lens through which we will make policy changes,” said Acquah. It will also “evaluate equity as it relates to the district’s organizational structure.”

The district announced the formation and leaders of committees on logistics, developing partnerships, systems change and research, professional learning, and communications.

“Simply put, the lives of each and every child that are connected to the school district of Philadelphia depend on this work of the equity coalition,” said April Brown, principal of the Laura Waring Elementary School in Center City, who will head the professional learning group. .

The project will be complemented by the Equity Partners Fellowship, which includes a class of 20 “equity fellows,” described as a year-long experiential learning opportunity for school staff — including central office administrators, school-based teachers, principals and support staff, and high school students. The fellows, who will be named and begin work this year, will lead equity groups within their school or office and mentor future cohorts, Acquah said.

The goal of the fellowship is to “build an army of equity champions across our district,” she added.

The admissions policies for magnet schools have resulted in the underrepresentation of Black and Latino students at the city’s most selective high schools, Central and Masterman. Alumni of the schools have demanded changes.

At the same time, the process this year is likely to be different because the pandemic upended the traditional metrics used to assess student qualifications, Hite said. No standardized tests were administered last year and grading policies were thrown into turmoil after school buildings closed in March. Attendance also is harder to measure in a virtual environment. Figuring out what to do this year is a separate undertaking, he said.

Philadelphia, the poorest big city in America, is a mostly Black and Latino district surrounded by mostly white, affluent suburbs, an example of the systemic racism and segregation common to metropolitan areas.

“There is disparity in housing, access to resources, and nutrition and health care, there are significant concentrations of poverty in and around the city of Philadelphia,” he said. “Those are all things that we can lament,” he said. “But as a district, there are also things that we can do to ensure that at least when children are in schools or in this organization, they have every opportunity to achieve, and it’s not going to be based on who they are, or where they live.”