At his final press conference in Philadelphia Thursday morning, Superintendent William Hite was characteristically reserved and businesslike. He explained how the district is honoring LGTBQIA+ staff and students for Pride Month and spelled out how young people can access meals when schools are closed this summer.

Then he turned the focus to a few star graduating seniors who are headed off to college and the military or starting their first jobs. One of them, Sarah Church, who is graduating from West Philadelphia High School and is off to Kutztown University to study criminal justice, took a moment to thank him. She noted that when Hite took over as superintendent in 2012, she was attending Thomas G. Moore Elementary school.

“During his decade of leadership, he has worked tirelessly to provide everyone with where resources are necessary to continue our growth beyond our time here in Philadelphia. As I leave the district, I know my fellow students are set up for success because of this,” she said.

Not everyone viewed him with the same rosy glow. While he always presented an unflappable front, in 2020, the Board of Education gave him a “needs improvement” rating for academic progress and systems leadership. Another low point of his time in office was the botched relocation of Science Leadership Academy into Benjamin Franklin High School, where construction problems delayed the opening of both schools for a semester.

Hite also came in for relentless criticism over charter schools, which educate more than 80,000 students, compared to about 110,000 in the district. While he long declared himself “agnostic” on the best type of school, few new charters were approved during his tenure. And he’s come to the conclusion that the charter movement has not fulfilled its mission of transforming public education.

On Thursday, Hite was asked what he would miss most when he leaves his post next week.

“What I’ll miss most are the children and the students, I’ll be missing these young people and seeing what they’ve achieved even though they have struggles,” Hite said. “That’s one reason I wanted to finish my press conferences with stories from young people.”

Tony Watlington, former superintendent of the Rowan-Salisbury school district in North Carolina, will be sworn in as Hite’s replacement on June 16.

Hite sat down Wednesday with Chalkbeat for an interview about his tenure at the district. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Why did you want to come to Philadelphia?

I wanted to come to Philadelphia simply because I saw inner city youth that needed something very different in terms of their education, and their conditions for their education. And also, there were (school reform) commissioners who were highly professional, who were focused on creating better conditions for the district, and who wanted to fundamentally change the trajectory of things like the financing, the budget, facilities, the work conditions, and so on.

Then I started talking to people in Philadelphia and to a person, everyone wanted to see something better for their children.

What do you think your main accomplishment has been?

More children are graduating from high school, we went from having over a billion-dollar deficit to having a balanced budget for the last four and a half years, and is projected to be balanced even beyond the expiration of the federal [pandemic relief] dollars. We have new systems for support for young people, like more counselors, nurses, and more music programs. We have structures that exist that help school-based staff with dealing with the social and emotional needs of children.

We had 16 “persistently dangerous” schools when I arrived. This is the sixth or seventh year where we have none. We have hydration stations now in all schools. We have a student information system.

We have more schools now that are air conditioned. We have more children in high performing schools. We have children who will graduate high school with an associate’s degree because of the new programs we’ve established.

So I think that it’s a body of work that becomes a set of accomplishments versus one thing. Last year, the most important thing for me was getting children back in school. And that still remains the most important thing, keeping them there.

Your biggest regret?

Cutting programs for students. I had to actually cut programs for students in 2013. I thought we could solve the budget shortfall by cutting people, counselors, bilingual counseling assistants, itinerant art teachers, we even started the year without extra-curricular activities.

The second biggest regret was not getting children back in school after more than a year out during the pandemic.

Looking back, is there anything you would have done differently in handling the COVID crisis?

We were forced to take children out of schools. The governor made that decision. In hindsight, now we know a lot more than we did then. If we were able to get masks faster, perhaps we could have had children back in school sooner. And you know, I think people did the best they could, especially our teachers.

But I would have tried to work to get students back sooner, much sooner, because they were struggling being out.

You were Philadelphia’s first permanent Black male superintendent. How do you think you did in terms of improving outcomes for students of color, especially Black males?

That’s the basis of our equity work. And that’s the work I’m also proud of, we have to know what the disproportionate data tells us about children – who are we suspending, who is in AP courses, who’s graduating, who’s reading on grade level. And then it’s also important to look at the policies and structures that we have in place.

When I got here, we had a “zero tolerance” policy around student behavior. Who do you think was put out of schools most often? Black males and Latino males. And so we eliminated that policy, in fact, we prohibited suspensions from kindergarten through third grade.

We have more children in these categories who are accessing opportunities, like [applying to selective schools] that didn’t have access to those opportunities before.

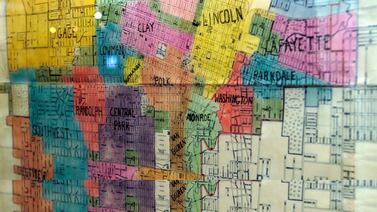

A recent report found that schools in this region are among the most segregated in the country in terms of race and class. Do you think that desegregation is even worth talking about and that more desegregation in schools would be beneficial? And how would we try to make it happen?

I think it is worth bringing up, but in the context of equity compensation. Because there’s certain populations that need something more and different in order to be successful. The issue becomes providing every single child with what they need in order to be successful, irrespective of where they are attending schools. The whole point is having good schools close to where children live.

Lifting kids out of their neighborhood and community in some cases doesn’t serve the purpose we would like to see it serve.

So what is the biggest obstacle to providing a great school for every kid regardless of where they live?

One obstacle has always been insufficient resources, another our fundamental beliefs about what our children can achieve. And I do think we have to have a different mindset about our children in the city of Philadelphia that allows them to access all types of opportunities. In some cases, facilities become an obstacle because there’s so much work that’s needed in and around [outdated] facilities. And I think gun violence is becoming an obstacle.

What role can schools play in trying to alleviate gun violence?

We just had a meeting with students yesterday who said the only place they feel safe is at school. And in the next breath they said we need to take out all metal detectors. We can provide safe spaces and teach them ways to resolve conflict differently.

Schools have to return to those sacred spaces where children don’t have to worry about being shot at or beat up or harassed or assaulted. You teach children how to talk about their emotions. You put young people in restorative circles so they can talk about their feelings. You do positive behavior interventions. You have youth courts where students actually do the adjudication of discipline. But when children are worried about coming to and from school, it’s going to impact what happens in schools.

Last year, we lost 30 children [to violence]. This year, we already have 22. That’s 52 children over not even two complete years. So that, to me, is at a crisis level. If a fourth grader saw someone shot in the street, the trauma services will go into that school for that day. But then the next day they’re called to the next school because there’s another traumatic event, but the fourth grader still needs that service.

We need to increase dramatically the services that are available to all children. And we have to sound the alarm that the district cannot do that alone.

Philadelphia, like the rest of the country, has experienced a teacher shortage. Why is that happening?

It’s happening because people have been talking down on the profession for the last two decades. Individuals are thinking, “I don’t want to be a teacher.” So we have to lift up the teaching profession for young people and think about teaching as leadership rather than just teaching [academic] content. These are people teaching young people social responsibility and social justice. I think we have to do a much better job of rebranding what teaching means today.

The answers to the teacher shortage are sitting in classrooms right now. We have to find ways to maybe do a Middle College type program for the development of teachers.

What have you been telling the next superintendent, Tony Watlington?

I’m telling him to learn as much as he can about the city and communities here. And oh, by the way, that’s going to take time. It’s him making sure he’s not frustrated because he’s not learning fast enough. He just has to remain patient, purposeful and intentional. To the public, I would say: People have to give him a chance.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.