Sign up for Chalkbeat Philadelphia’s free newsletter to keep up with the city’s public school system.

A plan to put in place Mayor Cherelle Parker’s promise to lengthen the school day and year — her signature education proposal — is taking shape.

But what that will look like in practice is still very much in flux.

Last week, Superintendent Tony Watlington told the City Council during an education budget hearing that a “beefed up” extended-day program will start in September in an unspecified number of schools, mostly consisting of “fun and engaging” after-school activities. In the 2025-26 school year, the district plans to offer a year-round schedule in up to 20 pilot schools, he said.

The first step of implementing Parker’s vision is adding programs and offerings this summer. But changing school districts’ traditional calendars to fully adopt year-round school is a different animal. It has typically meant shortening summer vacation and adding four week-long breaks during the school year. That shift, if it ever occurs, will not begin for well over a year, based on Watlington’s timeline.

It is very rare for year-round school to actually add instructional days. And the strategic plan adopted by the district last year cast doubt on the power of reallocating school days to improve academic achievement.

Putting in place an extended schedule — as opposed to offering more robust summer options — will need buy-in from the district’s unions, parents and other stakeholders, including agencies that now provide after-school and summer programming.

Cost has also not been discussed, though Watlington said he is seeking philanthropic help. And there are practical considerations linked to expanding programming at any particular school, such as whether it’s air-conditioned. Most city schools are not. (Eagles quarterback Jalen Hurts just donated $200,000 to install air conditioners in 10 schools.)

“We have to create a demand and build partnerships,” Watlington told the council.

Watlington has mentioned the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York City as one model he’s studied. Its Promise Academy charter schools’ schedules run from September through July, with week-long breaks in October, December, April, and June. The schools don’t have a longer day, but do have extensive after-school activities, and they also offer after-school and summer enrichment programs for students in New York City district-run schools within the zone.

During her campaign, when she discussed her reasons for supporting year-round school, Parker emphasized the benefits and flexibility it would provide to parents more than the potential academic benefits for students. But she didn’t clarify exactly what she had in mind.

Since taking office in January, she has changed how she talks about the issue. She now describes her vision as giving more educational opportunities to the city’s children outside regular school hours while keeping them safe.

“School is the safest place they’ll be … Ward and June Cleaver, the Cosbys, is not the reality our children are living in,” Parker said last month at an education conference, referring to the bygone popular television shows “Leave it to Beaver” and “The Cosby Show,” which presented ideals of American family life.

Philadelphia has previously tried one model of year-round school — albeit on a very small scale. In 2000, Grover Washington Middle School in Kensington operated on a shorter summer vacation with longer breaks during the year.

The goal was to reverse the effects of “summer slide,” or the decline in students’ achievement levels after the long summer break. But just four years later, the district’s then-CEO Paul Vallas ended the program, saying that its negligible academic benefits didn’t justify continuing it.

Here’s what to know about Parker’s push for year-round schooling and how it compares to other cities’ initiatives:

What’s new — and returning — for students this summer?

Both the city and the district already have extensive summer programming.

But the Summer Achievers program, which will be new this summer, could be especially significant. That’s because the 20 schools that could eventually participate in the 2025-26 pilot for year-round school will likely be drawn from the 62 schools where Summer Achievers programs will take place.

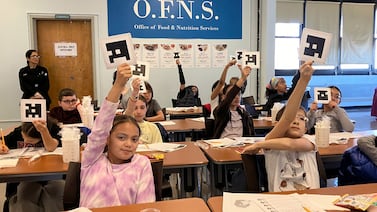

In Summer Achievers, in the mornings, students will receive instruction from district teachers in English Language Arts and math, while the afternoons and Friday will include camp-like activities and field trips. The program will also feature music, art, and sports, as well as social-emotional learning. The district is calling it a “school meets camp” experience.

This idea isn’t entirely new. A version of such a program was offered by the district starting in the summer of 2021, as schools began reopening after COVID.

Summer Achievers will be held between June 25 and Aug. 2. (For the program’s final week, the camp activities will take up full days and there will be no academic instruction.) While children in Summer Achievers will receive breakfast and lunch, families will be responsible for transportation.

The list of providers include the Greater Philadelphia YMCA, the University of Pennsylvania, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, and Sunrise Philadelphia. Summer Achievers is based on pilot programs held over the past three summers, funded in part by the William Penn Foundation. (Chalkbeat receives funding from the William Penn Foundation.)

A statement from the Office of Children and Families described Summer Achievers as “a model for what summer programming can look like … in a full-day, year-round program moving forward.”

Another new program for this summer is called “Young Entrepreneurs” and is for rising ninth graders. It will run from June 25 to July 25, and will focus on developing business skills as well as providing instruction in English Language Arts and math.

The school district already offers a considerable array of summer programming for young people between the ages of 5 and 18. They range from a two-day-a-week virtual program for students entering kindergarten to month-long courses for high schoolers to make up credits for courses they failed.

Several emphasize particular skills and interests, including music – there’s an option to join a summer orchestra and a summer drumline.

Others are focused on particular populations, including a longstanding “extended school year” program for students with disabilities to shore up their skills and a “newcomer academy” for English learners.

The city recreation department runs camps around the city, and the Office of Children and Families oversees nearly 100 programs run by Boys’ and Girls’ clubs and other organizations called “It’s a Summer Thing!”

In addition, Deputy Mayor for Children and Families Vanessa Garrett-Hartley said the city is planning to provide up to 8,000 summer employment opportunities and career exploration activities for young people ages 12 and up.

It’s “work based learning, internships, job shadowing,” Garrett-Hartley said.

What will year-round school mean for teachers?

Teachers remain wary of what officials might ultimately come up with, a sentiment rooted in last year’s mayoral race.

Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, said in an interview that Parker never discussed her proposal for year-round school with the union before making it a centerpiece of her campaign.

Without having more details, he said, his members have expressed concerns about how it may affect their jobs and schedules.

Some are also parents, he noted, “and if they have to work during the summer, this will totally impact their families and they don’t want to do that.”

In Philadelphia, the Belmont charter school network has its own extended-year program. Teachers in the network who sign up to teach over the summer get a few weeks off between the end of the regular academic year and the start of summer programming. They also get two weeks off before going back to Belmont in the fall.

But if parents have children in different schools on different schedules, year-round school could present more of a problem than a help.

All teacher participation in summer programs are voluntary; it is unclear what will happen if school schedules are changed. In the meantime, Jordan is praising the addition of enrichment activities and field trips to students over the summer, because many city children never have the opportunity to visit attractions like the Franklin Institute or the Constitution Center.

“All of this is going on around them and they are just not aware of it, and parents don’t have the funds to take them to museums, they can be costly for one child much less for three or four,” Jordan said.

What are the next steps for year-round school?

The logistics are daunting and the cost considerable. But one city councilmember said that after asking Watlington about it during budget hearings, she thinks the district is moving too slowly on the initiative.

“It wasn’t as well thought out as I thought it would be,” said Cindy Bass, who represents the 8th District in Northwest Philadelphia.”It’s hopeful, aspirational, not concrete.”

“This is the mayor’s directive. I was expecting more substantive detail,” Bass added.

Parker has separately proposed giving the school district a larger share of the city property tax, increasing its share from 55% to 56%, which she said would raise $129 million over five years. Bass said that money should be used for year-round schooling.

The school district already spends $42 million on summer and after-school programming, although COVID aid that helped pay for it is about to expire

Sharon Ward, the deputy chief education officer, said city, district, and other officials are meeting to hash out the details for this summer and for the future.

Echoing Parker’s comments from last year’s mayoral campaign, she noted that parents want more safety and enriching programs for their kids that are “more aligned with their work hours.”

Ward also said that “additional academic enrichment” will be a part of whatever’s developed, and that the city will learn from the activities already available to students.

“We’re working on it. We’re not starting from scratch,” Ward said.

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in Philadelphia. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.