This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Board of Education voted Thursday to revoke the charters of two long-embattled charter schools, while renewing the charter of a third on the condition that it entirely revamp its special education programming and enrollment.

The board also approved over a billion dollars in new financing, including what officials say was the largest new loan in over a decade, laying the groundwork for what it hopes will be three years of major infrastructure upgrades.

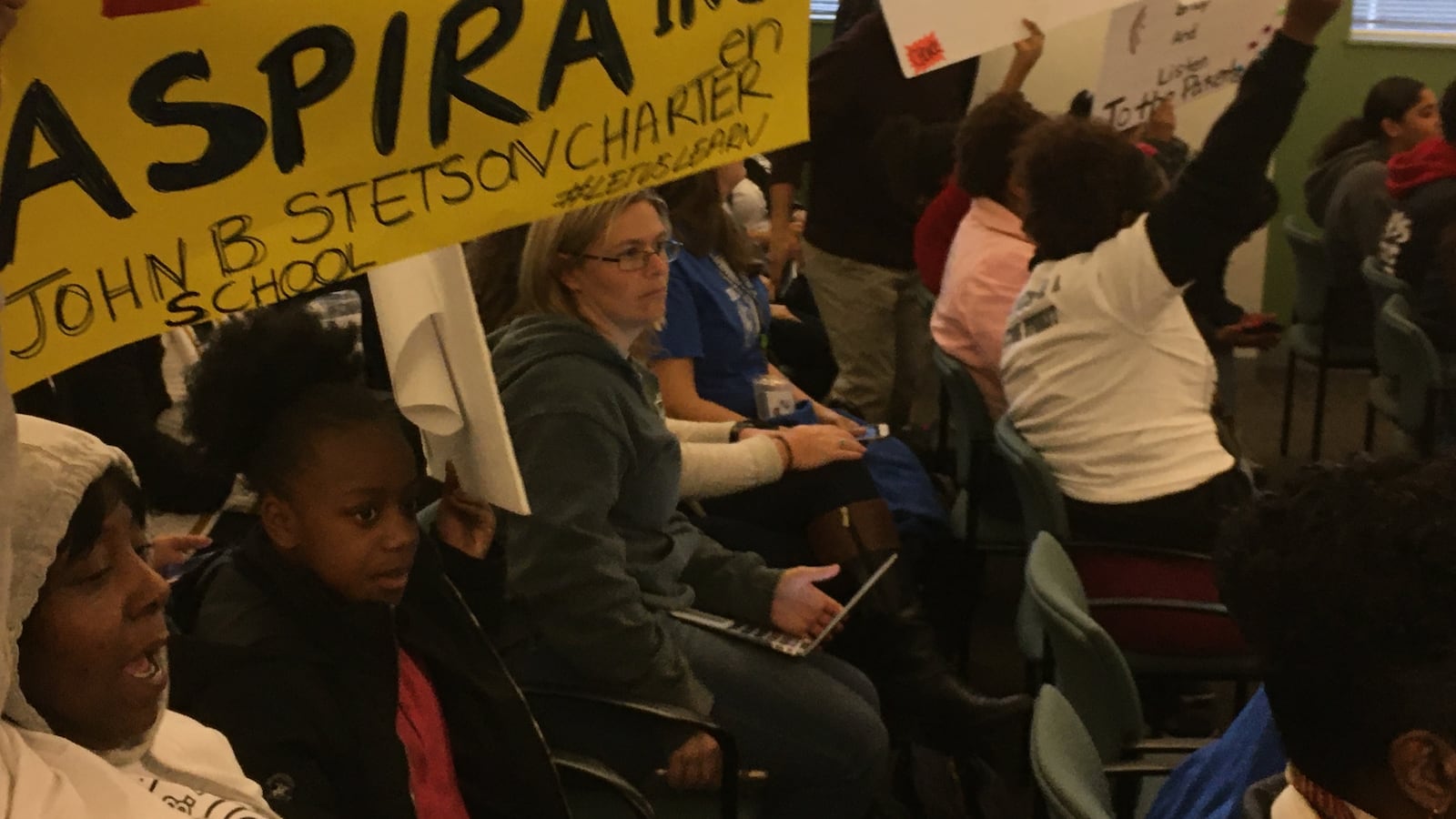

The board’s 8-1 votes to revoke the nonprofit ASPIRA’s charters for Olney High and Stetson Middle School followed a long session of passionate testimony from the schools’ parents, students, and staff.

“You can keep a great school open by giving us more time,” said Olney staffer Dan LaSalle. “Give us a chance.”

ASPIRA’s financial controller Xin Li told the board that the nonprofit’s books are in considerably better shape than in years past.

“I have witnessed striking improvements in internal controls,” he said. “The schools have turned around.”

And parent Doris Thayer warned that removing ASPIRA would bring back the bad old days of fights, truancy, and general disorder. “If you take them out, you’re going to regret it,” she said. “Olney is going to go back to the way it used to be.”

Several board members expressed great reluctance to close a program that has drawn praise for improving school climate and boosting enrollment.

“I’m extremely conflicted,” said Mallory Fix Lopez, the only board member to vote to leave the schools in ASPIRA’s control. “I keep going back to this idea of what is in the best interest of the kids. … Having taught in that area, before Stetson was a Renaissance school, I know exactly what is being talked about.”

Several other board members expressed similar reservations. But member Christopher McGinley responded with a stern warning: Leaving the schools open in the face of overwhelming evidence of poor performance, he said, would undermine the credibility of the entire charter oversight process.

“We approve the charter office, we approve their policies,” McGinley said, urging the board to accept the conclusions of the lengthy non-renewal hearings, which documented extensive academic and financial problems. “Two different teams three years apart came and said, ‘Don’t renew this charter. It’s not fiscally responsible.’ … If we ignore that, I don’t know how we’d say no to any charter in the future.”

Board President Joyce Wilkerson was more blunt: Climate improvements aren’t enough to offset consistently low test scores and dicey finances.

“This isn’t a hard decision for me. I value the cultural aspects of these schools … but without the academic achievement, I think we’re cheating our children moving forward,” Wilkerson said. “This school is not getting it done. … It’s time that we turn the corner on this.”

Added Board Vice President Wayne Walker: “When I see the [non-renewal hearing] officer’s report and the fiscal misconduct and the low academic scores, I have no choice.”

The vote to revoke the charters will likely trigger a lengthy appeal, which District officials say could last up to two years. In the meantime, Superintendent William Hite said, the District will launch a transition process of its own, with community meetings about programming and a recruitment push to keep existing staff.

Hite said he wouldn’t rule out a role for ASPIRA in the future of the school.

“If there are ways to continue to work with ASPIRA as a contracting group to provide some services, we would be looking particularly to continue things done around climate and ELL [English-language learning],” he said.

But staff members worry that the ongoing uncertainty about the schools’ fate will be disruptive no matter what the outcome.

“We’re losing teachers each year due to the renewal process,” said Stetson teacher Elizabeth Cesarini. “We’ll probably lose more after tonight.”

Special master for Math, Civics & Sciences charter

The board approved a new charter for a third school, Mathematics, Civics & Sciences Charter School (MCSCS), but added an unusual condition designed to address its persistently low rates of special education students and English-language learners.

The charter for MCSCS includes a call for a “special master” who will oversee a “complete overhaul” of the school’s special education programming, said Christina Grant, interim head of the Charter Schools Office. The special master will be chosen by the District, but paid by the school, Grant said.

If the school doesn’t follow the special master’s requirements, the terms of the new agreement allow the District to move quickly to revoke its charter, Grant said, instead of waiting for the end of its five-year term.

“Failure to follow that policy would allow the CSO to present to the board a case for non-renewal that’s outside the renewal process,” she said.

The school brought no staff or supporters to speak on its behalf. However, the board heard testimony from attorney Paige Joki of the Education Law Center, who filed a lawsuit Thursday on behalf of a parent who says her child was denied admission because of her special education status.

MCSCS has far fewer special education students than similar District and charter schools, said Joki – between 3 and 6 percent of its enrollment over the last three years, she said, compared to as much as 18 percent in comparable District schools.

“This difference is striking,” she said, adding that “during this time period, MCS has served no English-language learners.”

The new agreement includes 19 conditions for the charter, Grant said: five in academic areas and the remaining 14 in financial and organizational issues. She did not detail the nature of the conditions. Unlike the provision involving the special master, the only penalty for failing to meet the other requirements is a recommendation of non-renewal when MCSCS reaches the end of its five-year term.

Board President Wilkerson noted that such conditions have proven relatively toothless in the past.

“We, from time to time, have conditions, and five years later, they have not been met. … It renders the whole condition process essentially meaningless,” she said.

However, the addition of the special master was enough to secure a renewal from an otherwise uncertain board, by an 8-1 vote. Julia Danzy voted “yes … with ambivalence.” McGinley noted that his “yes” came “only because we have the clause about putting in a special master to ensure that students receive the services they’re entitled to.” Lee Huang echoed the point: “The inclusion of the special master was an important piece.”

New financing for capital upgrades

The board approved what officials say is about $1.1 billion of new financing, including what finance chief Uri Monson called the District’s largest loan “since the Paul Vallas years.”

The new finances are expected to help fund a three-year surge of infrastructure upgrades across the District, said Hite, including new roofs, electrical work, and lead and asbestos remediation. An issue of “green bonds” will support energy-efficiency projects.

The District will also use some of the funds to hire new project managers, including consultants and new District staff, in part to ensure that the District sees no repeats of the Ben Franklin High/Science Leadership Academy fiasco that displaced 1,000 students after construction work dislodged asbestos in the building.

About half of the new financing comes in the form of new bonds, along with savings from restructuring existing obligations. But the District also secured a loan of $500 million at “the lowest rate we’ve had in years,” said Monson, due in large part to the District’s rising credit rating.

“This is the first time we’ve been above junk bond status since 1977,” Monson said.

The move to borrow, said board member Huang, was driven by both need and opportunity. “The combination of our higher credit rating, low rates in the marketplace, and lots of projects that capital dollars could be used for,” encouraged the District to do “a significant amount of borrowing.”

The new dollars, a combination of loans and bond issues, “allows us to take an approach that other large municipalities have done,” said Hite, which is to seek “a firm to manage the projects. … We would also use a portion of this to expand our internal capacity.”

Funds from much of the new bond issue are required to be spent within three years, said Hite. He hopes to have a construction management firm in place by December, but notes that a lesson of the Ben Franklin/SLA incident is that building up his own administration’s capacity is “extremely important” as well.

Monson said that the fact that the new financing can be used to build staff capacity is critical; a burst of new projects will bring a host of new administrative demands, and 440 will have to be ready to handle them.

“The point is spending money wisely,” Monson said. “Unfortunately it’s become a bragging point how thin our administration is – but it’s too thin.”

School Planning Review

Hite provided a brief update on the District’s newly launched Comprehensive School Planning Review (CSPR), a strategic planning process designed to assess changing neighborhood demographics, and reorganize catchment boundaries, feeder patterns, and academic and capital investments.

“We want families in the city to want to attend their public schools, so we’re excited to begin this work,” said Hite.

The planning review will initially focus on parts of South, West and North Philadelphia, looking at school capacity and “how our population and communities are projected to change over time.”

“We want to look at our facilities and how they’re utilized,” said Hite. “We don’t just want to talk about [District] facilities, but about assets that are around the city … that could enhance programming at schools.”

The District has begun to create advisory committees of community members, said Hite, and seeks to open the doors as widely as possible. Principals are already recruiting members on their own, but anyone is welcome to take part, he said, adding that information on joining committees is available on the District website.

“We want as many people as possible to participate,” Hite said, adding that the recommendations of those committees and District staff will ultimately help the District direct capital dollars.

The multi-year process will take a close look at the facilities and capacity of District-run neighborhood schools, with an eye toward ensuring that every neighborhood has a solid K-12 feeder network, along with access to pre-K and an “equitable” share of resources and programs. The CSPR process won’t look closely at the capacity of magnet and special-admission schools, said Hite, because their enrollment isn’t catchment-driven.

It will, however, look at the enrollment patterns of particular communities to see which sorts of special-admission programs attract a given neighborhood’s students.

Hite’s team has sent conflicting messages about the role of magnets and special-admits in the CSPR process in recent weeks, and tonight’s statements were the first definitive answer on the subject. Board member Fix Lopez noted that this confusion should serve as a warning to Hite to make sure his communication practices stay up to the task.

“This is a question that’s been asked multiple times in multiple months,” she said. “There’s been misinformation around this, and that’s concerning.”