Although Philadelphia schools have a budget surplus that tops half a billion dollars, that rosy picture could turn very dark over the next several years, the district’s top financial official told board of education members Thursday.

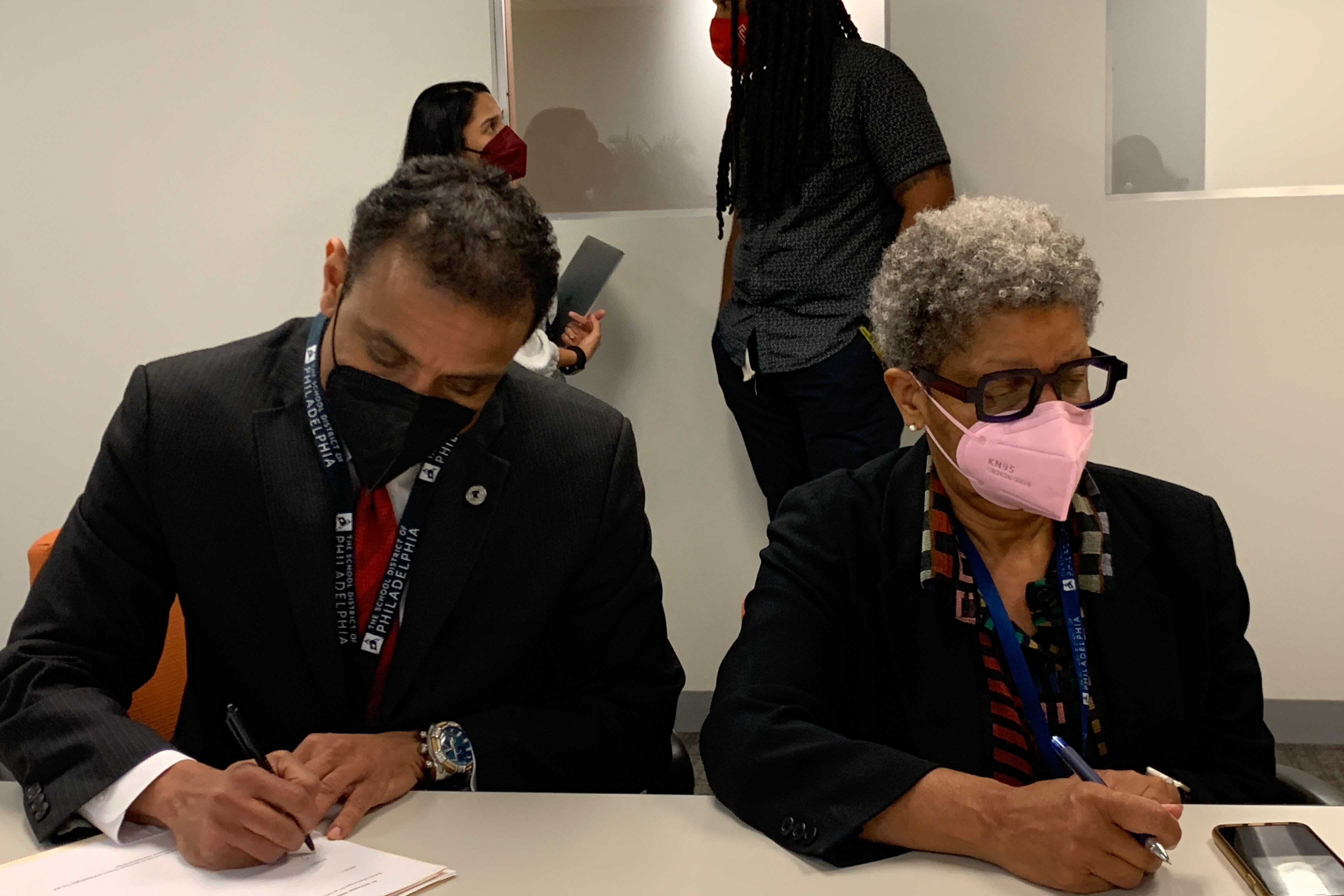

The district is slated to have a $515 million fund balance in its nearly $4 billion budget at the end of this fiscal year, Chief Financial Officer Uri Monson said. But he added that, based on current conditions, he forecasts that the district will be in the red by fiscal 2027 and have a shortfall of $484 million that year.

The growth in the district’s costs are projected to outpace revenue growth over the next several years, Monson said, due to the end of federal pandemic aid coupled with current state and local tax policies and funding mechanisms.

If that sort of shortfall occurs, the district will ultimately face tough choices and may have to cut a variety of staff positions and programs, including those focused on countering COVID’s effects. That could mean reductions in mental health services, after-school activities, bilingual counseling assistants, and support for students who have been traumatized by gun violence. And while Philadelphia is putting federal pandemic education funding to a variety of uses, the district will eventually use up that money.

“If we want to keep those things, we have to identify additional sources of revenue,” he said. “If they are left in, we’ll be showing massive deficits very quickly.”

Monson noted that the district has no power to alter parts of its budget like payments to charter schools, which are dictated by the state, and debt service. He acknowledged that the district can’t claim desperation given its current surplus, but stressed that it will still “need help” down the road.

Philadelphia’s school board is the only one in Pennsylvania that cannot raise its own taxes, and is entirely dependent on the city and state for its revenue.

Earlier this month, Gov. Tom Wolf signed a state budget for the upcoming year that increased state school aid for districts for basic and special education by $850 million. About $177 million of that increase will come to Philadelphia next year, Monson said.

Board of Education President Joyce Wilkerson expressed appreciation Thursday for that additional funding, although Wolf had asked the General Assembly for an increase of $1.8 billion in education spending. Previously, Monson projected that Wolf’s budget request would have provided $204 million more to the city’s public schools than the enacted budget.

District officials are especially concerned about the long-term impact of charter funding on the district’s fiscal health. Wolf had asked state lawmakers for significant changes in how charter and cyber charter schools are funded in ways that would have benefited school districts’ budgets. But the legislature approved none of Wolf’s proposed charter revisions.

Monson said that Philadelphia’s charter payments for special education students “have grown exponentially and unrelated to the actual services provided.” Monson’s new five-year plan shows that charter costs for the district are projected to increase by 10.4% from fiscal 2023 to fiscal 2027, while expenditures in district-run schools are projected to decrease by 1.9%.

“I don’t believe any other state awards dollars to charter schools the way Pennsylvania does, and I don’t think the current formula creates a sustainable environment for districts like Philadelphia with such a large charter sector,” said board member Chau Wing Lam, who has a background in government finance and whose daughter goes to a city charter school.

Despite the current surplus, some board members were very blunt Thursday about where things stand. Funding policies need “systemic change,” said board member Mallory Fix Lopez. Another board member, Reginald Streater, said the district is in a “perpetual state of robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

Dale Mezzacappa is a senior writer for Chalkbeat Philadelphia, where she covers K-12 schools and early childhood education in the city. She is a former president of the Education Writers Association. Contact Dale at dmezzacappa@chalkbeat.org.