This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Update: Mayor Kenney has issued a “stay at home” order for all Philadelphians starting Monday.

The world has ground to a halt, and here at the A.W. Christy Recreation Center, Amar Cropper was ready for it to start up again.

“I would have never thought that I would want to go back to work. But I want to go back, and it’s only been four days. I want to go back to school, too,” said the lanky high school junior. “I must have the coronavirus, thinking like that.”

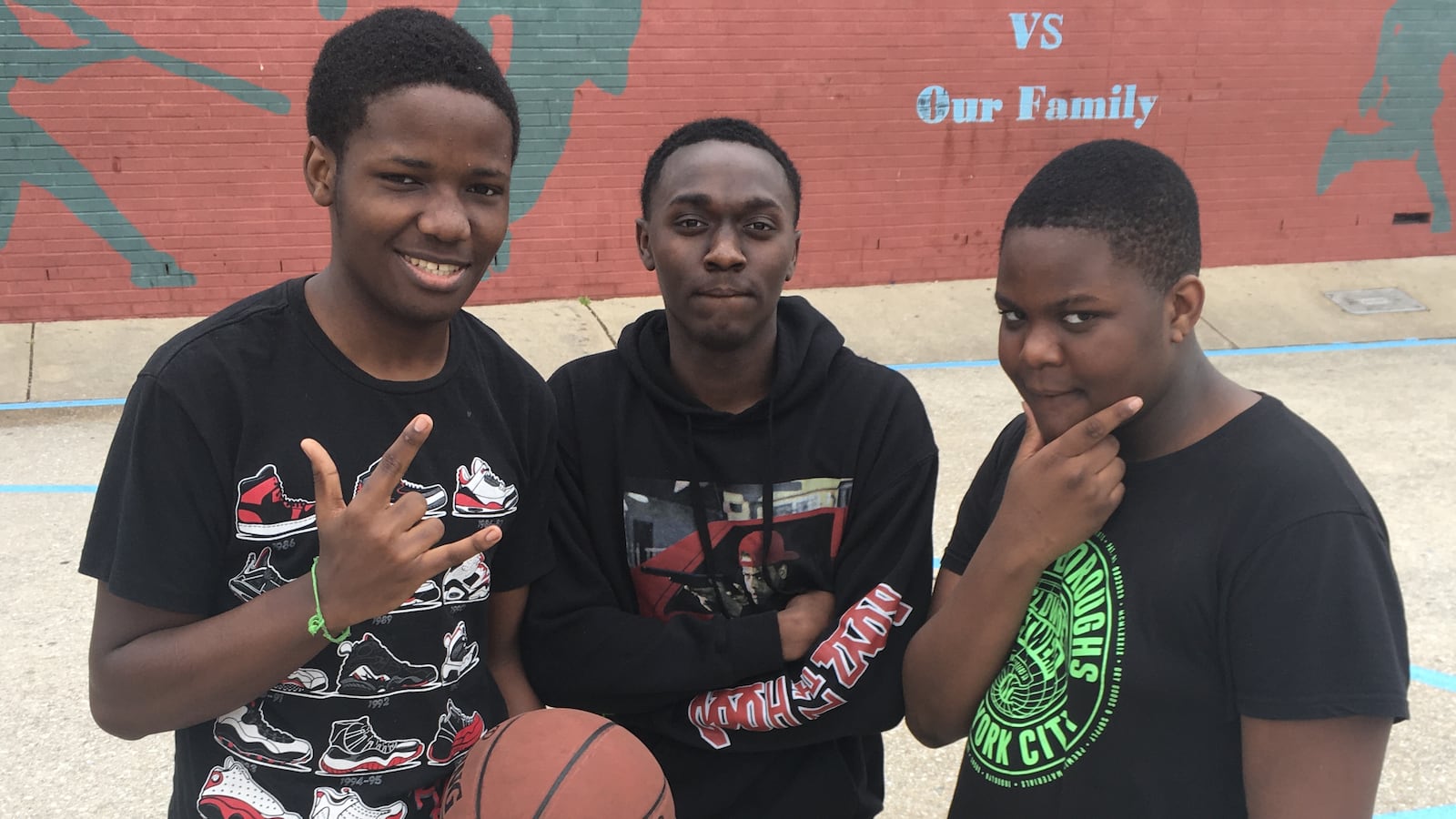

It was a breezy Thursday afternoon in Southwest Philadelphia, and Cropper and two friends were goofing around on the Christy basketball court. Around them, the streets of rowhomes were quiet. The playground behind them sat empty. By the next day, it would be closed, like others citywide, but on that day, the most visible sign of the coronavirus crisis was the table of free lunches laid out for students. Over the next hour, most sat untouched as city workers waited and chatted softly.

Most kids in this neighborhood are holed up at home with their families, these young men said. Their own after-school jobs are on hold – they work for a commercial cleaning company, but because of the shutdown, there’s “no work for two weeks,” Cropper said. There’s less and less for them to do every day, they say, and it’s not normal.

People aren’t meant to just hang around doing nothing, “like a cigarette with no lighter,” said Cropper, 16.

His friends agreed: Life without school is getting old fast.

“I got a lot of friends. I do kind of miss them,” said Alei Stephens, 13, an 8th grader. “I ain’t going to lie, I hate being out of school.”

Two of the friends, Cropper and Tirrell Blocker, 19, are high school students at cyber charters. Their schools are shut down for the moment, they say, with teachers unable to go to their offices to provide “live” instruction. Stephens is a student at KIPP West, a brick-and-mortar charter school, which is also closed, as are all other Pennsylvania schools.

The three were given some homework, and they planned to catch up on some missed assignments, but that’s the extent of their academic plans. For the most part, they’re on their own until classes start up again, and they have no idea when that will happen.

They know school is officially meant to re-start in a week, but when they watch the news reports, they see the crisis deepening, not improving. They see fewer and fewer people on the streets, and more and more wearing masks. Cropper concluded that he won’t be back in school anytime soon.

“Probably May,” he says, but he doesn’t know for sure. If anyone else does, whether in District headquarters, City Hall, Harrisburg or Washington, D.C., they won’t say.

‘Unprecedented’ lack of guidance

Since Pennsylvania’s public schools closed abruptly on March 16, no public official has said a word about how they can safely re-open. The federal government has provided no clear guidelines or directives. State and city officials have shared no official re-opening criteria of their own.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus crisis is worsening. Expert projections indicate that coronavirus infections may not peak until the summer. Cities and states are ramping up preparations to handle hundreds, perhaps thousands of life-threatening cases. Several states have already given up on the rest of the school year. Pennsylvania has cancelled all of its standardized testing, and the federal Department of Education has said all other states can do the same.

Amidst all this, the Philadelphia School District remains officially set to re-open on March 30.

If that seems impossible, no public official is ready to admit it. Advocates say such officials are in an “unprecedented” situation, forced to navigate a public health crisis without the kind of firm federal guidance that has been routinely provided in the past. In Philadelphia, city officials said they’ve been forced to look abroad and to other states for answers, not to Washington.

“Actions like those being taken in Philadelphia have never happened before anywhere. There are no best practices, no guidance, no advice,” said James Garrow, spokesperson for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

“We are intently watching what’s happening in other countries and states to learn from their situations and response actions,” Garrow said.

That leaves educators, students and families in the dark about when exactly school might return.

For the young men at Christy, all the coronavirus means right now is no school, no work, no answers, and a nearly deserted basketball court. The three friends didn’t yet know that City Hall was about to shut down rec centers completely, but they could see the writing on the wall.

“Usually when you come to the park it would be mad packed,” says Stephens. “But now there’s nobody here. Nobody coming.”

Around the nation, states, cities and school districts are coming to terms with the fact that the school year will be profoundly disrupted, or even cancelled.

“Basically, for all intents and purposes, school is over for the year,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of the School Superintendents Association in Washington.

In Philadelphia, Donna Cooper of the child advocate group Public Citizens for Children and Youth sees the same signs. The District should commit right away to a year that replaces most traditional schooling with creative alternatives, she said, solving equity and academic issues as best it can.

“I would say we should jettison the terms ‘instruction’ and ‘grading’, and assume the year is where it is,” Cooper said. “We need to be rapidly building the infrastructure for home instruction.”

Cooper is just one of many now asking big questions about “distance learning” and other techniques for engaging students through the crisis and beyond. But how much disruption school districts must plan for remains completely unknown. No federal guidelines exist to tell state and local officials when it’s safe for students and staff to return.

Instead, the White House and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have offered schools little beyond conflicting recommendations about public gatherings. The CDC has shared a set of vague “considerations” for school districts, which say that closing schools for two weeks won’t help reduce infections, but that closing them for eight weeks or longer might – or might not. A conference call scheduled for March 17 between the CDC and school superintendents was abruptly cancelled.

The leadership vacuum has left educators around the nation to make decisions on their own – an unprecedented situation, said Domenech. “At the national level, there’s been an abdication of any decision-making. They’re leaving it up to mayors and governors and superintendents.”

During past public health crises, such as the 2009 swine flu outbreak and the 2014 Ebola scare, states and school districts had firm federal guidance, he said.

Domenech said he’s been trying for days to get some clarity from the White House and CDC about what exactly constitutes an unsafe gathering, but “nobody is willing to give me an answer.”

Governors taking charge

Governors around the nation have responded by issuing a range of closure orders and recommendations of their own – orders that are being revised as the fast-moving crisis develops.

Since the coronavirus shutdown began in early March, Education Week estimates that more than half of the nation’s schools have been closed – some 91,000 public and private schools in all, serving about 42 million students. Large urban districts like Philadelphia’s held out for as long as possible, worried about the impact of closures on families that need to work and students who need to eat.

But many governors, including Pennsylvania’s Gov. Wolf, decided to override those concerns. Those decisions were driven in part by contagion models like that of the United Kingdom’s Imperial College, which predicted that the “modest mitigation” efforts like those underway in the United States could still lead to as many as 1.5 million deaths, many resulting from shortages in equipment and hospital beds.

Although most school closures were initially announced as temporary, lasting two to six weeks, educators and officials quickly began to consider the possibility of a much longer shutdown.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine staked out the most drastic position early in the crisis, saying that “it would not surprise me at all if schools did not open again this year.” Soon after, Kansas became the first state to cancel the remainder of the spring semester. California is considering the same move: “Few [schools] if any, will open before the summer break,” said Gov. Gavin Newsom.

As of this writing, numerous states are considering lengthening their shutdowns. New Jersey’s schools are already closed indefinitely. Delaware and North Carolina are considering closing beyond two weeks. Maine and Arizona will close schools until well into April. Alaska’s are closed until May. Texas could shut down for the year.

If Pennsylvania officials are considering any such changes, officials haven’t said so.

“We recognize that schools and their students and families have questions,” said Eric Levis, spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Education, but he could offer no answers about how the state will decide when schools are safe to re-open.

“As the department develops guidance,” he said, “we will share that information with school leaders and post it to the [PDE] website as soon as possible.”

District officials are likewise quiet. As of Friday, the red banner atop the District website no longer indicates that schools will re-open March 30. Instead it says simply that “the School District of Philadelphia remains closed,” with no indication of when classes will re-start.

The situation is “unprecedented,” said District spokesperson Monica Lewis. “A lot is unknown right now.”

How much school closures will help slow the spread of the virus remains unclear. As soon as closures began, some observers warned that they may create more problems than they solve by disrupting low-income families’ lives. The CDC’s “considerations” for school districts offered little clarity, saying that “other mitigation efforts” like hand-washing and social distancing may “have more impact” than school closures, and that “places who closed school (e.g., Hong Kong) have not had more success in reducing spread than those that did not (e.g., Singapore).”

And to complicate matters, experts say the disease is now deeply entrenched, and that “community spread” is inevitable. Some states have determined that it is now too late for containment strategies like South Korea’s that depend on testing and isolating those who carry the virus, and they’re shifting toward a strategy of prioritizing care for those suffering from its life-threatening symptoms.

What such rapid changes mean for school districts is unclear. Large scale testing to show community-wide infection rates is nowhere in sight, said Domenech, and that leaves school districts to try to fight the virus without knowing where it is.

“We don’t know who really has it,” said Domenech.

But what is clear at the moment is that the crisis is getting worse, not better. Since the coronavirus was first documented in Pennsylvania two weeks ago, the state has identified 371 confirmed infections and two deaths. Philadelphia now has 67 known cases.

Pennsylvania state officials say the crisis is just beginning. “We need everyone to take COVID-19 seriously,” said the state’s secretary of health, Dr. Rachel Levine, on Saturday.

“Pennsylvanians have a very important job right now: Stay calm, stay home and stay safe,” Levine said. “We have seen case counts continue to increase, and the best way to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is to stay home.”

Seeking refuge

Back at Christy, staying home for the next few months is not the friends’ favorite option. Four days of near-lockdown has been more than enough.

“I hate it. I hate it!” says Stephens. “It’s crazy because, now, I want to go to school. I hate staying in the house.”

Alei Stephens gets in one last shot at the Christy Rec Center last Thursday. All athletic courts are now closed.

Even as he spoke, the friends were about to lose their basketball court. That Thursday afternoon, city officials announced the closure Friday of all athletic fields and rec centers. The friends knew that was possible, and said it would be a blow to them and their neighbors.

“Most people around here are trying to do good. When you come to the playground, it’s like unity,” Cropper says. “People hanging, playing ball, people who had a beef work it out … its tranquility. It’s a safe space. You don’t have to worry about anything here.”

When kids and adults are cooped up together for too long, all sorts of trouble can break out, and people need somewhere to go to let off steam.

The rec center has been that place, the young men say.

“It’s like, where else we going to go? You don’t want to be in the house all day,” says Blocker. If school stays closed into May or June, Blocker said, “that’s crazy! We might get sick and tired of seeing each other’s faces.”

But the friends know that a lengthy shutdown seems likely. National leaders are coming to the same conclusion.

“We can all see from the exposure growth that in two or three weeks, the infection rate is going to be two or three times higher [than now]. And we’re going to reopen schools? No way,” said Domenech.

The problem is fundamental, Domenech said: Officials can’t re-open schools with confidence unless some combination of data and expert analysis tells them it’s reasonably safe to do so. Right now, that data doesn’t exist, and state and local officials are being left to decide for themselves which experts to trust, he said.

PCCY’s Cooper says legislators should “immediately” guarantee full funding for up to eight weeks of school this summer, if that is even possible. Meanwhile, educators need to figure out how to navigate the “equity” concerns and start supporting students remotely, distributing laptops and finding other ways to serve Philadelphia’s diverse community of students, she said.

“Kids could continue to learn. They could create portfolios of learning if we can support them with phone calls” and other distance-learning techniques, Cooper said.

For the young men shooting hoops at Christy, the main hope is simply to get through this and get things back to something like normal.

They say they’re confident that they can keep up with their studies while schools are closed, and they don’t want to get sick. “I don’t want this virus. I’ve got stuff to do,” says Cropper.

Nor do they want to see their families or neighbors get infected. But they also want to be studying again, working again, and hanging out with their friends again. And they know the risks that await young people if schools stay closed for weeks or months.

“When you’re in regular school, the teacher’s on you, do your work!” says Blocker. “But when you’re home by yourself, you can just do nothing.”