This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

As he enters his eighth year as Philadelphia schools’ superintendent – he is the longest-serving District leader since Constance Clayton (1982-93) – William Hite is emphasizing a story of steady progress and consistent focus on crucial goals.

To be sure, he acknowledges, city schools still face daunting obstacles of concentrated poverty and financial struggles abetted by a broken state funding system.

“The things that school districts don’t do well is maintain a focus on things they’ve set out to accomplish,” Hite said in a back-to-school interview on Tuesday. “They start a lot of things, add a lot of things, and it feels like a lot of activity and energy. One thing that is important here in Philadelphia, we’re focused on the same things as last year.”

Among the most important: improving early literacy and getting more students to graduate with “the skills and ability to pursue their aspirations and dreams.” Other areas of focus include recruiting and retaining talented teachers and stepping up facilities repairs and upgrades.

News coverage of unsafe conditions in school buildings helped the District get additional resources to deal with problems such as lead contamination and asbestos, although he said the District was working before within its limited means to address them.

“It drew attention and resources to help us solve the problem,” he said of the coverage. “It drew attention to areas in which we were patching stuff that needed more than a patch.”

Over the summer, he said, lead stabilization was completed in 18 schools and the District installed 150 new air conditioners in six schools, spending $24 million in school renovations above and beyond normal maintenance. “We have made a significant investment in that space,” Hite said.

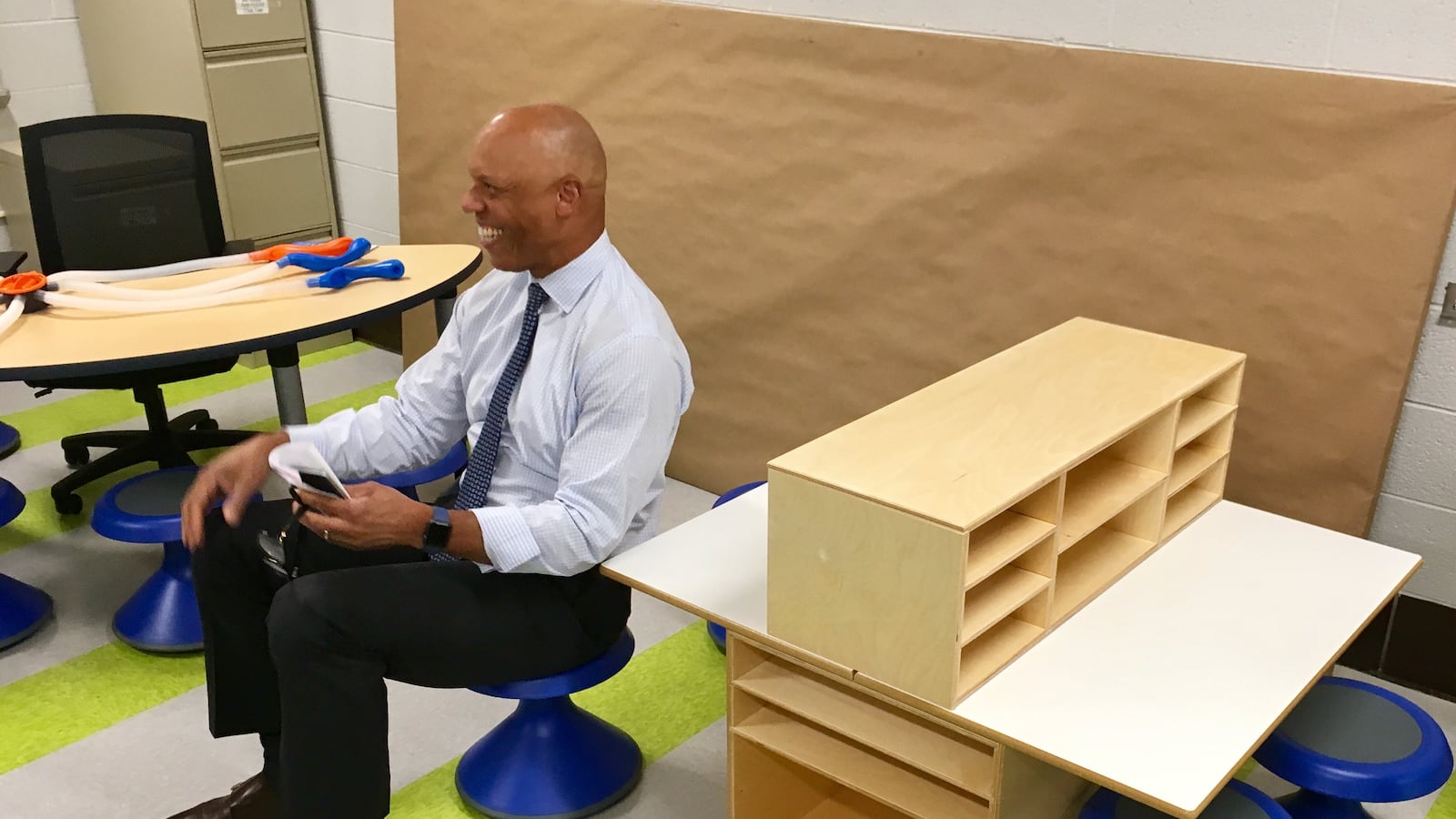

In addition, “We continue to modernize classrooms.” he said. An additional 132 K-3 classrooms were modernized this summer, bringing the total to 363, meaning that they received new lights, new ceilings, new floors, and new technology and educational materials.

“There are lots of movable objects for children to bound on and move around on,” he said. All K-3 teachers have also been trained to use new “leveled libraries” that include books at color-coded reading levels that students can use to advance their skills.

Being able to read proficiently by 3rd grade is a crucial benchmark for future success, and the District has made significant progress in that area, although more than half of students still read below grade level.

He will open the school year on Sept. 3 at Robert Morris Elementary in North Philadelphia, one of the schools whose classrooms for early grades have been modernized. Hite wants to build excitement for the opening through #ringthebellPHL, encouraging families to post on social media ringing a bell – any bell – in anticipation of the new school year.

Over the last two years, the District has spent $422 million in capital and operating funds for classroom improvements. A District assessment in 2017 found that it would take nearly $5 billion to fully make safe and modernize all the District’s facilities.

Resources remain spare relative to the needs, but the District is not in crisis mode the way it was in earlier years of Hite’s tenure, when dozens of schools were closed, thousands of teachers laid off, and there was uncertainty over whether the District could even open on time.

The District hired nearly 700 new teachers and counselors to start the year, and Hite said that as of Tuesday there were just 62 unfilled positions. Keeping the District adequately staffed is always a struggle, but he says that it is far better than several years ago.

“We have a 99 percent fill rate. I challenge you to find another urban school district that has that type of a fill rate. That’s not to say 100 people may not resign between now and first day of school. But we are working hard to fill the vacancies, and we are trying to communicate a broader story. Instead of Philly has a terrible problem, we’re saying we want you to come here, start your family here, and bring your children to our schools.”

Data show that teacher attrition is still high – more than half of new teachers leave before the five-year mark – but that is a national problem as well.

Hite acknowledged the stark disparities in conditions between teaching in the city and in some neighboring suburban districts, where salaries are higher and conditions less stressful.

“Over in Lower Merion or Abington, that’s night and day … so dramatically different,” he said. He recalled how hard it was to recruit in years when “I don’t know if we can open [schools] if we don’t get $50 million now, and teachers get a letter around the holidays saying maybe this is your last paycheck. … That is not recruiting material. It is survival material.”

But survival is often the story of urban U.S. schools, which, as a matter of policy, generally receive fewer resources to educate the neediest students. Although Philadelphia is not in crisis mode at the moment, not much progress has been made since Hite arrived in making Pennsylvania’s system for funding schools adequate and equitable. The Commonwealth has some of the largest gaps in spending in the nation between wealthy and poor districts.

Struggle for funding equity

Although the legislature adopted a new funding system that distributes state aid in a way that takes into account the actual needs of districts, accounting for poverty rates, the concentration of poverty, local taxing capacity, and other factors, that system applies only to new money. That’s less than 10 percent now. A “hold harmless” clause ensures that no district gets less than it did the year before even if it has lost enrollment, which tends to put larger urban districts at a disadvantage. The General Assembly has balked at making changes because it would result in many shrinking – and in many cases poor – districts seeing a dip in aid.

But if all the funds were distributed through the formula, Philadelphia would get more than $300 million in additional money each year.

“While we are happy that new dollars are coming through the formula that way, by and large it’s still inherently a system that’s not based on fundamental adequacy or fairness,” Hite said. In May, Hite joined other urban superintendents to protest in Harrisburg.

Gov. Wolf, a Democrat, campaigned on funneling significant new money into education and had grand ambitions to overhaul the tax system, including a state income tax increase, to pay for it. But those plans, made early in his first term, faced stiff opposition from Republican lawmakers and were never realized. Wolf soon settled for incremental increases each year and no significant formula changes for either basic education or charter schools. Pennsylvania’s charter funding system exacerbates the resource gap, because money that goes to charters comes from districts’ state allotments.

But Harrisburg has been at a stalemate regarding that as well. Last week, Wolf announced his intention to make some changes in policy involving charter schools through executive order, including some that the governor said would require them to adhere to the same standards as traditional district schools. Hite sees this as a move that “may make people be more motivated to do something. Anything there would be beneficial, as long as monies are distributed in a fairer way and based on the needs of young people.”

Still, Hite calls the continuing tension between District and charter schools as they spar over scarce resources in Philadelphia “a fake conversation … simply because the formula is so messed up. It doesn’t allow dollars to follow the children, and it punishes one group to fund another group.” The charter law and its method for funding schools have not been significantly amended since the law was first enacted in 1997. And half the state’s charters are in Philadelphia, so the city is dramatically affected.

When he arrived from Prince George’s County, Maryland, Hite got a swift lesson on Harrisburg’s attitude toward Philadelphia, and not much progress has been made on that score during his time here. The easing of the District’s immediate financial crisis has been due largely to a significantly larger investment in the schools from the city, he said.

Since he arrived, the city was able to regain control of the District from the state, which took it over in 2001, citing academic and financial distress. But under the 17-year reign of the School Reform Commission, the state did little, especially under Republican governors, to ease the perennial financial crisis and made more and more demands on the system. In some ways, it made it worse.

“I won’t opine on what Harrisburg is doing,” Hite said, “or why they’re doing it. We need a system that is fairer in terms of funding monies for facilities and educating children who, by and large, are coming from circumstances of poverty in higher percentages than in other places. That’s what we need. Somebody else has to ask the question of why we can’t get help for that.”

Comprehensive facilities planning

The District announced in May that it is embarking this year on a Comprehensive Planning Review that will take a look at its facilities in all city neighborhoods, making an effort to plan for the future as some neighborhoods may need more schools while the needs in others shrink. One goal is to create as many K-8 schools as possible instead of having a hodgepodge of grade configurations, and to expand preschool, Hite said.

Beyond that, Hite wouldn’t say much about what values underlie the planning amid signs that schools in some neighborhoods are becoming more popular with parents who traditionally haven’t used the public system in large numbers – i.e., the white middle class.

Values such as prioritizing school desegregation, for instance, would come out of the process instead of being predetermined, he said.

But equity is one value that Hite has embraced. He made a decision, controversial in some quarters, to move Science Leadership Academy, a selective admission school, into the same building as Benjamin Franklin High School, which is marked by high poverty and low achievement. He said that some good has already come from that move.

“The two student bodies have been working together to create a sense of community and involve their voice in this project,” he said. “The two communities are learning from each other. We’re looking to see students from different backgrounds having experiences together through either extracurricular activities or athletic programs.”

Equity initiative

One of the more interesting new initiatives being undertaken by the District this year is one that puts the focus squarely on race and equity by having people in the schools and central administration talk more openly about it.

The equity initiative includes staff training that seeks to get teachers and others to recognize and confront their implicit biases. At its last meeting, the Board of Education approved a $170,000 contract to hire the Equity Lab, a consulting firm, to work with top administrative staff so they “have the tools and mindset needed to be successful,” according to the resolution. The firm proposed “a robust engagement that will establish a common understanding of race, equity, diversity and inclusion principles.” It includes four days of development sessions, as well as individual coaching.

And at new-teacher orientation, the District launched a process to engage them in “equity circles” in their schools, in which they get together periodically to discuss and confront these issues and their own attitudes.

“It’s all about understanding the cultural context of how they’re working and how they will begin to develop relationships with young people and families to ensure that the child gets what the child needs in order to be successful,” he said.

“There are underlying tensions in many conversations about race, and we want, as a district, to talk a lot more about it and how it impacts our own understanding about our biases in issues associated with race, class, and to some extent, demographics,” he said. “We’re trying to get better at it as a district.”