This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Parents and students joined advocates in City Council on Monday to call for a new “community connector” staff position in every public school and funds to make $170 million in emergency building repairs identified by the teachers’ union.

They also demanded additional counselors and double the number of school air conditioners.

“The health of our schools is paramount,” said community organizer Kendra Brooks. “Not only the physical health of our schools, but the mental and emotional health of our students. Our children face trauma at an alarming rate.”

Brooks, who has children at Steele Elementary and Science Leadership Academy @ Beeber, said the community connector position was crucial to “build a bridge. … The ultimate goal is to improve the success of the students, and the best way to do that is by supporting the entire family.”

The hearing was called by Council member Helen Gym to highlight urgent school needs, many of which were brought on by state budget cuts during the administration of Gov. Tom Corbett. She was joined for most of the hearing by Council members Jannie Blackwell and Blondell Reynolds Brown.

Speakers at the meeting said that with the return of the School District to local control last year after nearly two decades under state control, it was time for City Council to step up.

“Now, in this election season, we are entering the first budget cycle with the new local board in place, and we have an opportunity to make good on the promise of that moment,” said Andrea Moselle, co-chair of the education team at the interfaith coalition POWER and a former District parent.

School board members Mallory Fix-Lopez, Angela McIver, and Julia Danzy watched from the audience.

Saying the city is “at a crossroads,” Moselle called for more community participation in the District’s decision-making. “Those closest to the pain must be leaders in the solutions.”

POWER, which includes members from more than 50 congregations, was a leader in the successful campaign to replace the state-dominated School Reform Commission with a local board. Now the group is campaigning to end the city’s 10-year tax abatement for new construction that costs the School District $61 million in potential revenue each year.

Moselle demanded funding for the emergency building repairs identified by the union.

“That investment would be a critical step towards keeping children safe,” she said. “But we cannot stop there. POWER also supports calls for stronger parent and community engagement, smaller caseloads for counselors who support students, and a strong focus on safe schoolyards.”

Gym, calling Council’s chambers “the People’s House,” spoke at the beginning of the hearing, applauding the grassroots work that has helped to restore so much lost from schools after the Corbett cuts, including all counselors and nurses. But she said there is much more work to be done.

Philadelphia City Council member Helen Gym presides over a hearing in Council chambers about the School District’s budget. (Photo: Greg Windle)

District officials will appear before Council next week for a budget hearing. They are forecasting small surpluses for the next two budget cycles, but expect funding shortfalls to begin again in 2021.

“The School District is in a position to invest,” she said. “We balanced budgets over the next several years. … Our conversation needs to be about priorities.”

Students from the Philadelphia Student Union, Asian Americans United, and Vietlead spoke about how their schools needed more funds and asked Council to support Gym’s call for the community connector position, as well as more counselors and social workers.

And they emphasized the need for heightened investment in building repairs.

“Coming from a different school environment in Indonesia barely a year ago, I was shocked at the conditions of the Furness [High School] building,” said Jason Woo, an organizer with Vietlead. He described “nasty” mold, chipping paint, cold classrooms in the winter, and hot classrooms in the summer.

“Sadly, I know that Furness is not the only school that experiences these toxic conditions,” Woo said. “I demand that every single student in Philly have a healthier and better environment.”

Minghui Wu, a graduate of Furness and an organizer with Asian Americans United, added complaints from students at Academy at Palumbo, which suffered water damage from a collapsed ceiling, and Northeast High School, where enrollment is 3,000 students and many classrooms lack air conditioning. When Wu was a high school student, his mother did not speak English and she worked seven days a week.

“She has no time to come to parent meetings,” Wu said. “But she does want that information. She wants to be a part of my education, but has too many barriers in the way.”

Now a student at Community College of Philadelphia, Wu described struggling to get information about financial aid forms and college applications from his school counselor.

“It wasn’t because he wasn’t dedicated – it was that he had way too many students and not enough time,” Wu said. “This struggle with the college process isn’t just for immigrant students, it is schoolwide.”

Jason Woo, a Furness High School student and an organizer with Vietlead, testifies before Council. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Jessica Way, a teacher at Franklin Learning Center, said she was shocked after four colleagues developed cancer over the last four years. They all teach on the same wing of the third floor, where the paint is flaking from frequent water damage.

“These women have children and one has grandchildren,” she said. “They are important members of our school community, and I am thankful that everyone so far can call themselves survivors.”

“It’s Teacher Appreciation Week, and I don’t want coffee or a mug,” Way said. “I would like the School District to get the money it needs to fix our schools, so we can have a cancer-free school year.”

Laurie Mazer, a parent at Jackson Elementary, testified on behalf of the Philadelphia Healthy Schools Initiative, which has joined with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers and advocacy groups to call attention to shoddy work to remediate toxins in schools.

The initiative now works with the District, having helped design new standards for work and communication with parents and staff.

“The $170 million sounds big in my world, but with the budget decisions you all have to make, it’s a small amount,” Mazer said to Council. “Mouse droppings, chipping lead paint, asbestos, and mold send the message that our kids don’t deserve anything better. We have to show them that we have a bare minimum duty to them to provide safe and clean learning environments.”

“I need the people in this room to start acting with urgency – as if it was your child who was poisoned by lead.”

Hillary Linardopolous, a lobbyist for the teachers’ union, called the city and District budgets “a reflection of priorities.” Of the 220 school buildings that the District studied in 2015, 155 can be classified as in “poor” or “critical” condition.

“Those schools represent more than 88,000 students who are learning in an environment each day that is quite literally poisoning them,” she said. “It represents thousands of educators experiencing the same.”

“For $170 million, we can abate the most pressing needs – including, but not limited to, water intrusion remediation, abatement of lead and asbestos, replacement of windows and ensuring that schools are online to be able to have air conditioning,” she said. “It would help address the rodent issue that roughly three-quarters of our schools face and invest in good paying cleaning jobs.

“It is not a panacea. It won’t bring our schools to equity. But it’s a critical start.”

The District itself has estimated it needs $5 billion to fully repair, remediate, and upgrade its aging stock of more than 300 school buildings.

A warning to Council

Public Citizens for Children & Youth (PCCY) executive director Donna Cooper cautioned Council against interpreting the balanced budget as a reason to avoid giving the District the additional funds it asked for, which is what happened last year.

“Just because the District is not in fiscal turmoil does not mean the District yet has the funds, infrastructure, or talent needed to deliver a world-class education,” Cooper said. “The new normal inflicted on us by the Corbett budget cuts – and we’re just now getting to balance – is something we must all resist considering acceptable.”

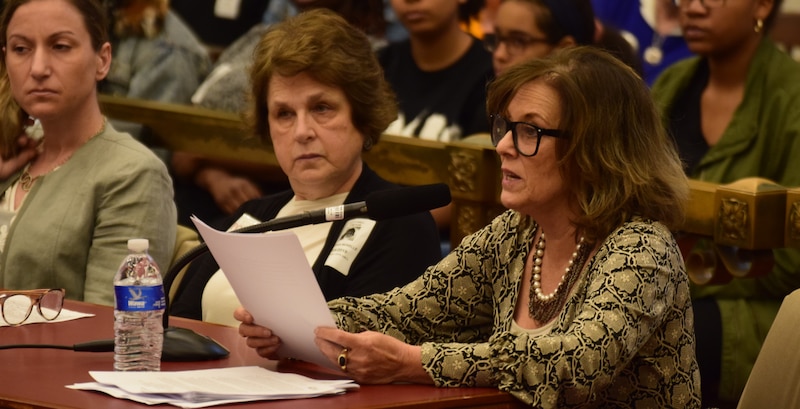

Donna Cooper of Public Citizens for Children & Youth testifies before City Council (Photo: Greg Windle)

The District’s proposed $3.4 billion budget represents a 7.4 percent increase over last year, but most of the increase is due to fixed costs, including higher charter school payments and built-in salary growth, not additional investments in schools and classrooms.

Cooper said the District’s fund balance this year $160 million resulted from reduced borrowing costs, due to “strong reserves.” The District was able to issue more bonds last year to fund school construction and renovation projects.

“But, given the urgent needs of our students, the District should expend at least half of the funds it has on hand in a responsible manner for urgent one-time facility upgrades that we know are needed to keep our children safe.”

She called for the increased capacity needed to install air conditioning in many schools as one example.

She also urged Council to consider spending on additional counselors and school-based support as an investment that can save money on other expenses.

The District has an average of one counselor for every 392 students, but the American School Counselor Association recommends one for every 250 students. Because of the way the counselors are allocated, in some schools, there may be just one for more than 900 students.

Cooper pointed out that the District spends more than $77 million on students in residential placements.

“The District could avoid a substantial portion of these costs if more counselors and school psychologists were hired to help students, because far too many of them suffer from heart-wrenching trauma,” Cooper said. “And we have to put the resources in place to heal and teach them, not incarcerate them.”

The need for more community liaisons

Brent Johnstone co-founded Fathers Read 365, which distributes books to low-income families and encourages fathers to read to their children every day. Since 2017, it has given away 15,000 books – 7,500 at public schools in North Philadelphia.

But Johnstone had to use personal connections to get meetings inside these schools. He was at the hearing to speak in favor of funding the community connector position, which would allow his nonprofit, and others like it, to get into more schools.

“For a parent trying to get involved and advocate for their child, it can be lonely and difficult,” Johnstone said. “Families trying to navigate their school system too often feel alone – but they don’t have to. … Some schools are anchored in their communities, and it shows.”

Brent Johnstone, co-founder of Fathers Read 365, asks City Council for more funding for city schools. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Johnstone works in one school where there was a shooting outside “that some children had seen, and it’s never addressed in school.”

“We need help, and we can help each other,” he said.

Johnstone wants community connectors to be “actively engaged” in seeking parent feedback and finding outside resources from nonprofits and the local business community.

“But we need the backing of Council — of the people who decide where our money goes.”

Under questioning from Gym, Linardopoulos said the District once had two part-time positions that were similar to community connectors. But those were among the positions eliminated after the state budget cuts.

Christina Jackson, parent of twins in kindergarten at Henry C. Lea Elementary, spoke with pride and joy about her children’s school. She lauded the work of its family and community engagement liaison, a similar position to the proposed community connectors. But most schools don’t have a liaison, and school climate staff are part-time.

“We know not all schools are as fortunate as Lea,” Jackson said. “For so many families, but particularly black, brown, and immigrant families, the weight of negative school experiences persists. Family engagement is linked to improved school climate and better academic outcomes for children, but it is not easy. Part-time positions will not accomplish the goal of building stronger community.”

Christina Jackson, a parent at Lea Elementary, testifies before City Council. (Photo: Greg Windle)

Maura McInerney, legal director of the Education Law Center of Philadelphia, called for the District to better meet the needs of pregnant students, who account for 30 percent of high school dropouts. The ELC’s four-year study found these students are out of school for four to six weeks after having a child.

“Typically, during that time, students have no ongoing connection to teachers and receive no academic instruction,” McInerney said. And they are not eligible to apply for instruction at home for six weeks. “Funding is needed to ensure that these students receive the academic support they need while out of school, transition support upon reentry to school to make informed decisions about school placement, and that they receive accommodations to breastfeed upon returning to school, as well as access to child care.

“Providing these critical interventions will change the lives of two generations of students.”

Now a mother and a student at Temple University, Alexis Hearst attended Lincoln High School, where she knew mothers who took advantage of the school’s day care. But most high schools don’t have that.

“It’s important to get students back into school and not let having a child deter them,” Hearst said. She added that students infer the priority that society places on them from the conditions in their schools.

“Why even bother when you go to your school and see you’re not being treated the same way and your school’s not adequate compared to the schools out in the suburbs?”

Alexis Hearst, a Temple University student, testifies before City Council. (Photo: Greg Windle)