This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Philadelphia’s traditional charter schools enroll a smaller share of the city’s most disadvantaged students – those from the most poverty-stricken families, those who have special needs, and English language learners – than District-run schools do, according to a new report from the Education Law Center.

The findings suggest that the 58 schools “are not sharing equitably in the responsibility of educating all students,” the report said. Roughly 30 percent have no English language learners at all, it said. More than half of these charters are “hyper-segregated,” ELC stated, which is when more than two-thirds of a school’s students are from one racial group and less than 1 percent of them are white. Just 9 percent of District schools are hyper-segregated, the report found.

The ELC report stated that traditional charter schools as a whole “disproportionately enroll more advantaged students” and that this demographic difference gives these charters a “significant edge” in presenting themselves as more successful than District schools in academics and sustainability.

It also noted that traditional charters are more likely to be more than 50 percent white (12 percent of charters meet this criterion) than District schools are (5 percent meet the criterion) and more likely to be located in predominantly white neighborhoods. Overall in the District, about 15 percent of students are white.

Although the simple requirement that students must apply to enroll in charters already guarantees a self-selected population, “systemic charter practices exacerbate the differences between district and charter populations, deepening the ‘double segregation’ of race and poverty for students who remain in district schools,” the report said.

Charter proponents pushed back on the report’s conclusions and data analysis.

“We share ELC’s concerns around segregation and equitable access to high-quality schools, but charter schools are part of the solution, not the problem,” wrote Stephen DeMaura, executive director of Excellent Schools PA, in an email.

The ELC report did not include in its analysis 25 so-called Renaissance charters, which are converted District schools that are required to accept all students from a given catchment area. It also excluded cyber charters and several traditional charters for which it didn’t have enough data.

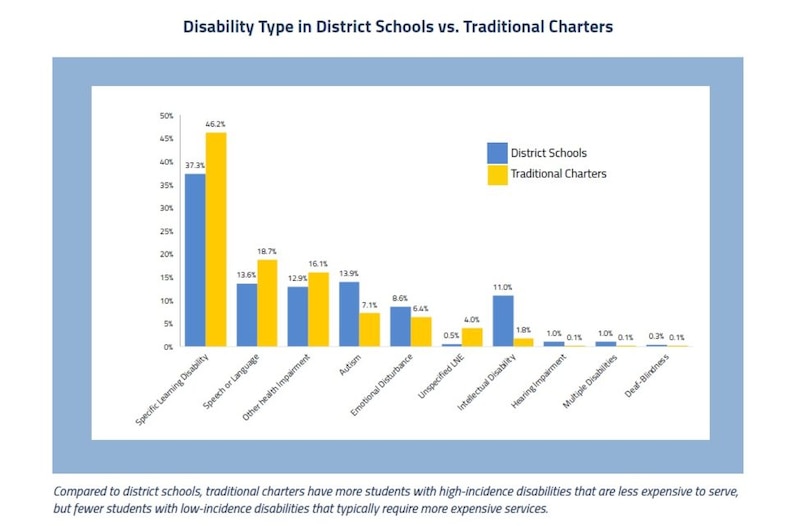

The state charter school law specifies that charter schools must not discriminate and must accept students by lottery, regardless of need or disability. ELC found that although overall, traditional charters and District-run schools serve a similar percentage of children with disabilities – 17 percent for District schools and 18 percent for charters – the charters serve comparatively few students with more severe and expensive learning needs.

For instance, nearly half the special education students who attend charters – 46 percent – have what is known as “specific learning disabilities” such as dyslexia and ADHD, which are more common and less costly for schools to meet their needs. In District schools, 37 percent of special education students meet that definition. At the same time, charters serve a lower percentage of students diagnosed with autism, serious emotional disturbances, intellectual impairment, and multiple disabilities – so-called “low incidence” diagnoses that are expensive and labor-intensive for schools.

The ELC report said that “roughly 40 percent of traditional charters failed to adhere to federal and state enrollment requirements designed to ensure that charters are truly accessible to all students in accordance with their mandate as public schools.”

ELC found that 22 of the 58 schools “were non-compliant with annual enrollment standards” specified by the charter law. These include asking for prohibited documents, such as a report card or transcript, medical records, parent/guardian identification documents, Social Security number, and a student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP), as well as asking parents to fill out a volunteer questionnaire.

Charters have “strikingly lower levels of economically disadvantaged students compared to district-run schools,” the report said. It stated that the poverty rate in District schools is 70 percent, compared to 56 percent in charters.

DeMaura, whose organization favors charters and school choice, fired back against ELC’s interpretation of the data.

“The segregation critique is especially confusing in light of the systemic segregation at play in the School District,” DeMaura said.

He said that 92 percent of about 20,000 students in the lowest-performing District schools – those with scores of 10 or less on the District’s own performance metric – are black or Latino. Parents want alternatives, he said, contending that these lowest-performing schools are more than half-empty, based on their building capacity.

David Hardy, founder of Boys’ Latin Charter School and now senior adviser to Excellent Schools PA, dismissed the analysis because, he said, people at ELC most likely don’t have to deal with failing schools in their own neighborhoods and so they don’t understand why poor families of color clamor for charter schools.

He said that the District as a whole is failing black boys in particular – the target population of his charter school, Boys’ Latin.

If charters are more socioeconomically diverse, with lower concentrations of poor children, as ELC says, Hardy contended, that is a good thing. Parents don’t want to send their children to schools where 100 percent of the students live in poverty, he said.

“If you see schools with economic diversity, that’s a clue that those schools are working for people,” he said.

Charter proponents have long maintained that the District’s selective admissions schools, many of which were created to promote racial desegregation, are contributing more to unequal educational opportunity in Philadelphia than charters do.

Both DeMaura and Hardy cited a 2017 report from the Pew Research Center showing that qualified black and Latinx students are less likely to apply to, be accepted, and attend the District’s selective admissions schools.

“The real racial barriers are inside the District,” said Hardy.

In its recommendations, ELC said that the state should restore the charter reimbursement line item in its budget, which sends money to districts to help defray the costs of charter expansion. When that line item was eliminated, Philadelphia lost $100 million a year, and due to the state’s funding methods, charter expansion has come at the expense of District schools.

It also urged that the Board of Education – which rejected three charter applications at its meeting on Feb. 28 – should “explicitly evaluate” whether charters are complying with federal and state civil rights laws and maintain admissions, hiring and operational practices that are “designed to promote equity,” in part by increasing the capacity of the Charter Schools Office so it can “provide appropriate oversight.”

DeMaura said he doesn’t disagree with those recommendations, but would not limit them to charter schools. “While they propose the standard to apply just to charter schools, we believe that all public schools should be held to those same standards,” he said. “It should be about access and results.”