This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Ask Superintendent William Hite why the Philadelphia School District has started a massive planning process now – an endeavor that could reshape the landscape of schools in the city – and he presents a simple fact: Five years ago, Mayfair Elementary School had 1,200 students. Today it has 2,400.

Once District leaders absorbed the magnitude of the upheaval in this modest Northeast rowhouse community, they launched the construction of a 10-classroom addition. They are now in the process of building an entirely new school in the neighborhood. But, for the most part, the District found itself in reaction mode, unprepared for such a dramatic shift in so short a time.

“We saw how quickly the demographics changed,” Hite said.

The questions arose: Where else was this happening? And what should we do?

After more than a year of preparation, the District has launched its attempt at finding answers: the Comprehensive School Planning Review (CSPR). By combining community input and demographic data, the process aims to bring equity and efficiency to a sprawling system and balance anticipated population changes, neighborhood and school histories, and the wishes of students and families.

It sounds logical and promising, but the initiative comes at a time when trust in the administration is at a low point, fueled by what the District acknowledges has been an inadequate response to alarming reports of potentially dangerous flaking asbestos in some schools. The Hite administration hopes to restore faith in its intentions and competence through an inclusive process that compiles reliable data and provides meaningful opportunities for school communities to help design plans for their neighborhoods.

Exactly what the plan might produce is unclear. So far, District leaders have articulated some basic goals. One is increasing access to pre-K, and another is refining the hodgepodge of grade configurations and feeder patterns in schools to create “thoughtful transitions” and sensible K-12 pathways. They also want to maximize building utilization so they can “invest limited capital dollars where needed most.”

The District is prepared to consider multiple options to achieve these goals, including closures, consolidations, expansions, new construction, and catchment area changes – all of which have wider implications. Many in-demand schools have large enrollments from outside their regular catchment areas, and these liberal transfer policies that parents are used to are likely to be tightened.

But there are minefields and questions aplenty. Redrawing catchment areas can upend property values. Issues about race and gentrification loom large.

Other districts, including New York City and San Francisco, are stressing racial and socioeconomic desegregation as one path to better schools. The reality that schools are stratified by race and income, which continues to define most urban areas in America, has even drawn the attention of Democratic presidential contenders. In an effort to address it, several of them have come out with plans encompassing not just educational improvement, but also increased investment in housing discrimination issues.

But although desegregation has been raised by some parents, most of them white, District leadership doesn’t see it as a path to Hite’s bottom-line goal – equity for all students.

“Different resources are needed for those learning to speak English, those who are two to three years behind in reading, for those who tend not to attend school regularly or graduate,” Hite said. “The equity question for me is making sure we’re able to provide those resources regardless of where they attend school.”

Aiming for a more open process

District officials promise that whatever CSPR produces will be much different from the situation that greeted Hite when he came to Philadelphia: the severe, top-down reorganization plan produced by the Boston Consultant Group (BCG) at the request of the state-run School Reform Commission. BCG, hired before Hite arrived, worked in secret and called for dramatic changes. When details emerged after a bruising right-to-know battle, it was revealed that BCG had 88 schools on a closure list.

Hite initially recommended closing 37 schools, and the District eventually shuttered 23.

“I never used the BCG report,” he said. “We went back and did a deeper analysis.”

Regardless, the result was an unprecedented downsizing, from which some neighborhoods are still reeling.

This time, Hite said, school communities will help drive the process from the start.

Now that process has begun. November saw the first of a series of CSPR community meetings in South, North and West Philadelphia. Local lawmakers, advocates, and organizers are just starting to learn what may lie ahead. Likewise, parents and school communities are beginning to discuss what this might mean for them.

At Meredith Elementary in South Philadelphia, parent Eugene Desyatnik sees a chance to resolve years of “uncertainty and confusion.” The popular school has a number of enrollment and overcrowding issues, and its neighboring schools sometimes suffer spillover effects. The chance to take part in something like CSPR is welcome, Desyatnik said, and parents “eagerly await the findings … as well as the opportunity to engage in further dialogue.”

Other parents and activists are still distrustful, fearing that this will be just another example of the city’s poorest areas getting the short end of the stick.

“They are trying to be proactive and organizing around what they see as an attack on neighborhood schools,” said Akira Drake Rodriguez, a lecturer in planning and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania, who has taken an interest in the CSPR and has been talking to parents around the city about their concerns.

Many, she said, “are certain that it will result in schools closing” and are worried that they will have little or no say. Parents in South Philadelphia, where there is a large immigrant community, have already noted that the invitation for parents to apply for a seat on the study area’s planning committee was only in English, she said.

Hite and Vanessa Benton, the District’s new deputy chief of planning and space management, said they can’t rule out closings and other potentially unpopular decisions.

But they are adamant that CSPR’s community engagement will be substantive and significant – although how the process will play out is still up in the air.

“We’re building the plane while flying it,” said Benton.

First plans are expected in March

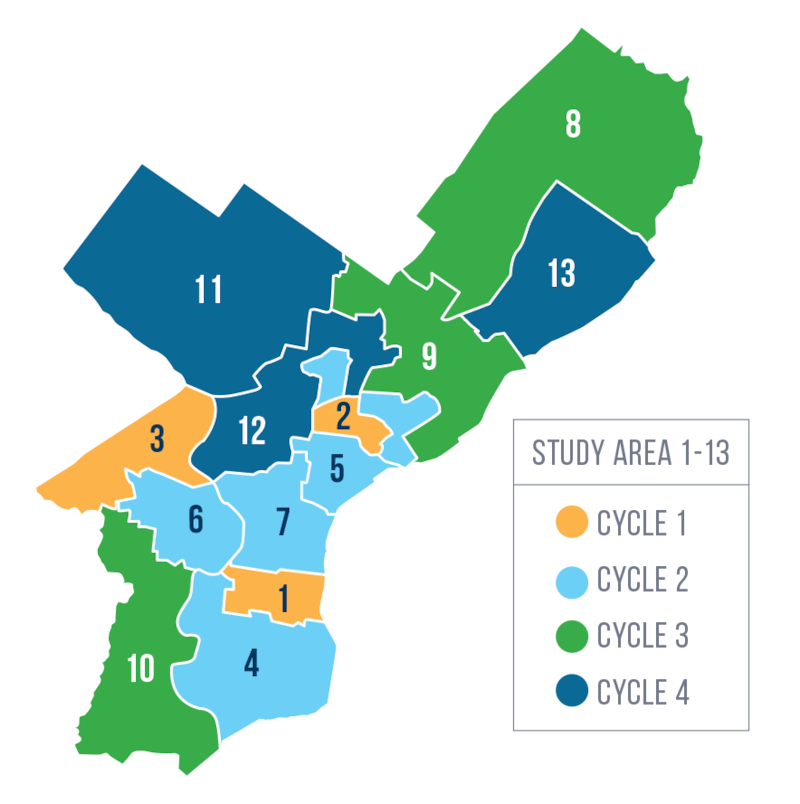

Map of the District’s Comprehensive School Planning Review cycle.

Unveiled by the District in the spring of 2019, the process is now underway in the first three of 13 study areas. Teachers, principals, parents, and community members are being invited to work with District staff to study data compiled by consultants, put their heads together, and come up with plans. The entire city will be covered in a five-year cycle, and then the process will start again.

However, the timeline is tight. The first three study areas will have just a few months to develop their basic plans.

Those in the first cycle – parts of South, West, and eastern North Philadelphia – are expected to develop a plan by March to present to the Board of Education in April. The board will hold public hearings and vote in June.

The South Philadelphia area includes 10 schools, some of which are overcrowded and some of which are not. But overall demand is up, and redrawn catchments and even a new school could be in play.

The North Philadelphia study group is east of Broad in one of the poorest sections of the city. It includes seven elementary schools, most with large Latino populations: Cramp, de Burgos, Elkin, Munoz-Marin, Potter-Thomas, Sheppard, and Willard. Here, underutilization, along with some particularly old school buildings, is at issue.

In West Philadelphia, just six schools are being studied, including two that were formerly District-run and are now operated by charter organizations. Here, too, the primary issue is underutilization. The schools – all of them elementaries – are Cassidy, Gompers, Lamberton, Mastery Mann, Overbrook Elementary, and Universal Bluford.

These first areas were chosen “because the needs there are most critical,” said Hite.

Selective admissions and transfers

As CSPR has taken its first steps, critics are voicing their first concerns. At recent Board of Education meetings, some parents – most of them white – have proposed controversial ideas such as ending selective admissions policies and, if schools must be closed, closing the magnets and putting their programming in neighborhood schools that are open to all.

The District plans to study migration to charters and selective schools to determine patterns. But the study process itself only involves neighborhood elementary schools, excluding high schools and schools with selective admissions.

“Is moving the special admissions programs into neighborhood school buildings … an option that is on the table?” asked parent and teacher Zoe Rooney at a meeting of the board’s Finance and Facilities Committee. “If closures are on the table, in terms of past history and equity, then perhaps those should be the physical schools that close this time around.”

Other parents have decried transfer practices that allow white parents to bypass their mostly black and low-income neighborhood school for a mostly white one nearby.

Stephanie King’s two children are among only a handful of white students at Kearny Elementary in Northern Liberties. She has testified several times before the Board of Education asking why the District allows some white students in the Kearny catchment to transfer to Adaire, a school in nearby Port Richmond that has been one of only two elementary schools in the city that are more than three-fourths white.

“Desegregation has to be addressed in the city,” King said. “It’s a foundational issue for educational equity and fairness, and I think that it’s such a driver for enrollment patterns that the District can’t keep its head in the sand.”

King believes that Philadelphia’s policies should be more forthright about confronting racial disparities.

“In New York City, they are willing to say segregation is the root of the problem,” King said. “In some areas, the city has changed enrollment policies with the idea of desegregating the schools. If you look at the catchment lines in Philadelphia, they could be redrawn to be more racially balanced.”

Such boundaries, she said, “don’t matter if you’re just going to let white people transfer wherever they want to.”

Board member Christopher McGinley said it is time to update the District’s transfer policy; known as Policy 206, it hasn’t been revised in 40 years. In many schools, out-of-catchment students make up more than half the enrollment. That begins to present a problem when a school becomes more popular within its neighborhood. One school where this is the case is Nebinger, in the South Philadelphia study group.

“I have raised this concern in public about having a method in place to monitor students transferring in from outside the community,” he said.

For many years, “principals have been allowed to let students in if [a school] is less than 90% full” without clear guidelines. Among other potential results of such an ad hoc transfer policy, McGinley said, “perpetuating segregation is a concern of mine.”

The District has a long history of allowing – in fact, encouraging – transfers to create more schools defined as desegregated. The practice was one response to a Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission anti-discrimination case against the District, which lasted 40 years. For decades, thousands of black students were bused to mostly Northeast schools to increase the proportion of black students to a 40% threshold.

A much smaller number of white students were bused away from their often all-black neighborhood schools to others that were very close to reaching a threshold of 25% white. Those parameters – at least 40% black, at least 25% white – satisfied the state’s court-ordered guidelines for desegregation.

But in Northern Liberties, the Kearny-Adaire transfers have the opposite result, noted King.

“I can’t get over the fact that I live in a neighborhood with a white school and a black school, and the District doesn’t do anything,” she said. “I think that schools that have a disproportionate number of white students should be prohibited from accepting white students from other catchments.”

In a school district that is 15% white, Adaire’s white population is 79%.

Inequity and racial segregation are inextricably linked, said Erica Frankenberg, a professor at Penn State University who has researched the subject for the Civil Rights Project, a national research and advocacy organization now based at UCLA.

Other cities are confronting this more directly. San Francisco, Frankenberg said, is undertaking a similar process and has been explicit that its equity goals include minimizing the number of schools that are predominantly poor and nonwhite. Although there are exceptions, these schools, regardless of which state they are in, are typically under-resourced and academically struggling, often with high staff turnover.

San Francisco and several other cities “are concerned about racial isolation and concentrated poverty, but those aren’t terms Philadelphia has mentioned,” Frankenberg said.

However, the African American leaders of the District – Hite and Board of Education President Joyce Wilkerson – do not necessarily agree that desegregation should be prioritized, although they certainly don’t oppose it if that’s what communities want.

“There are challenges, basic equity challenges, but you shouldn’t have to integrate a school to address those challenges,” said Wilkerson in an interview. “I’d rather educate kids where they are, with sufficient resources and high expectations.”

Desegregation by itself is no panacea, she maintains. A veteran herself of integrated schooling, she said that she and her family members experienced discrimination and low expectations in mostly white schools.

“Now that the state is collecting information of subgroups, I’m interested to see evidence on whether or not minority and poor kids get the benefits of being in an integrated community,” she said. At the same time, “We’ve got schools that are racially isolated where the kids really are achieving.”

However, she emphasized that this is her personal opinion and that the board as a whole might feel differently.

Mayfair neighborhood transformed

There are a number of reasons why Mayfair doubled its size in five years.

McGinley, who has family from the neighborhood, said the post-war neighborhood was heavily Catholic for decades. The Catholic school, St. Matthew’s, enrolled 1,500 students at its peak, while Mayfair had about 600 – half of what it had been built for. When the older residents moved or died, the area became popular with immigrants. The establishment of an International Baccalaureate curriculum at Mayfair accelerated the interest of many of the immigrant families, particularly Chinese Americans.

“This is a dense area where a lot of houses were converted to multifamily units,” said Hite. “One household became four households. It created a dynamic we had to look at.”

McGinley said that with the demise of Catholic schools, the growth of charter schools, and all the other moving parts, “Somebody is going to have to figure all this out.”

The person in charge of that effort is Benton.

She grew up in Philadelphia. She remembers going to schools that weren’t in her neighborhood, which was Logan. She attended Logan Elementary through grade 4, then was bused to Pennell for grades 5-6, followed by Wagner Middle School, and finally Frankford High School. Her assigned neighborhood schools would have been Jay Cooke and Gratz High School.

She doesn’t remember why she didn’t go to her neighborhood schools – “you’d have to ask my mother,” she said. Clearly, her mother faced a complex system even then.

Benton, who most recently worked for the Mastery Charter network, is the take-charge type. She’s no stranger to having fingers wagged at her by unhappy parents. This happened while she was the director of academic services in the Charlotte-Mecklenberg, N.C., school district during a reorganization process there. She is ready for whatever controversies may arise.

“I believe this is the right thing to do,” she said. “I’m not as concerned about me taking this personally as I am about making sure this process runs so at the end of the day, we have recommendations based on data and recommendations that are best for the students in the District.”