This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Federation of Teachers contract is set to expire in August, and in the battle for leadership of the union, incumbents and challengers alike are firing the first salvos.

The PFT’s leadership elections have not been formally scheduled by the union’s executive board, but will take place sometime between January and April.

On Thursday, members of the Caucus of Working Educators will formally introduce a slate of candidates who seek to replace PFT’s veteran executive team and create “a different kind of union” – more vocal, more engaged, and more committed to racial equity and other progressive causes.

“The time is now,” said the Caucus’ candidate for president, Kathleen Melville, a teacher at the Workshop School, pledging to follow the examples of Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and Chicago. By closely aligning with other unions, advocates, and organizers, she said, the PFT can win better contracts and advance social justice at the same time.

“We’re hearing from a lot of [PFT members] who are tired of seeing stuff passing us by,” she said.

Kathleen Melville

Current PFT president Jerry Jordan and his team have countered by saying that with the end of the School Reform Commission’s 17-year reign, the PFT now has the freedom it needs to effectively negotiate. State laws restricting the union’s negotiations to wage-and-benefit issues are no longer in effect, Jordan said. PFT members can now expect a “higher level of member engagement” over contract negotiations, he said, complete with a bargaining posture that includes the threat of a strike.

“Of course it’s a possibility. We’re negotiating under new laws,” said Jordan, who was elected PFT president in 2008 and has been on its contract negotiating team since 1992.

“A lot of the [PFT] members have only worked under the SRC, so they don’t know what it means to not be under the SRC,” he said.

Both the Caucus and the current leadership of the PFT, which is part of the American Federation of Teachers, say they plan to use the contract negotiations to fight not just for improved wages and benefits, but also for better working conditions, including a broad array of social support services for students. Likewise, both promise to give PFT members a greater voice in the process – something they didn’t have in the last contract negotiation.

What distinguishes the Caucus is its emphasis on alliance with other groups and causes.

Jordan and his team believe that now that negotiations aren’t legally restricted to wage-and-benefit issues as they were under the SRC, they’ll have the freedom to fight for things like smaller classes and mandatory support staff. His team will also continue to speak out on related issues, said Jordan, such as ending the 10-year tax abatement on most new construction in the city, which costs the School District tens of millions of dollars in annual revenue.

“We have been very clear that [more] funding is desperately needed” for schools, he said.

Melville and the Caucus team promise a more active approach, expanding the coalition of allies to win greater concessions – an approach sometimes referred to as “Bargaining for the Common Good,” a strategy endorsed by the National Education Association, plus a handful of AFT chapters and several other public sector unions.

It is well past time for Philadelphia to join this movement, Melville said. “It’s about asking people to step up,” she said. “Quite a few of us have tried to be involved, but we come away feeling disappointed, shut out of the process. … Some of the other unions show us that it really is possible.”

The challenge

The WE Caucus is a self-described progressive group of PFT members, focused on what’s sometimes called “social justice unionism.” Its slate of nine includes candidates for president, several vice presidents, treasurer, and secretary.

The group aims to replicate the successes of teachers’ unions in cities such as Los Angeles and Chicago, where a recent 11-day strike secured several key wins for teachers and residents.

Among the Chicago Teachers’ Union’s victories were traditional wage-and-benefit wins, such as pay raises across the board, including a dramatic 40% boost for paraprofessionals.

But the strike also netted some broader benefits, including bigger funding commitments from Chicago’s City Hall; an expanded corps of counselors, nurses, and social workers (including some specializing in “restorative justice”) for schools; special supports for homeless students; sanctuary protections for those who are undocumented; and gender-neutral bathrooms.

The strikers failed to win some demands, such as affordable-housing provisions. But they and their allies successfully expanded the funding debate by aggressively challenging Chicago’s broader financial practices, including various allegedly “dirty deals” involving real estate developers and Wall Street financiers. Although the union was not able to stop any of those big-dollar projects, highlighting their controversial aspects appears to have helped the strikers gain leverage in the funding negotiations.

Said CTU’s president, Jesse Sharkey: “Did we accomplish every single little thing? No. But I can say that we moved the needle on educational justice in the city.”

Melville said the WE Caucus would like to see a similar approach in Philadelphia, with the PFT working closely with other groups on overall city priorities, not just education spending. Like the Chicago union, the Caucus plans to build public support for its agenda by aggressively challenging city revenue policies that, they say, let well-endowed major institutions off the hook. Its platform calls for “including Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOTs) from local universities” as well as an end to the controversial tax abatement.

Advancing such an agenda would require the PFT to more actively align its goals with other unions and advocacy groups, such as those pushing for a higher minimum wage or better job protections, Melville said.

But the first step has to be better participation within the PFT itself, she said.

“What our current union is not doing a great job on is engaging members,” said Melville. “People will say of certain things, that’s kind of off-limits, but [Chicago] won them because of really engaged membership.”

Jordan promises strong stance

The PFT’s Jordan bristled at the notion that the current PFT leadership is anything less than progressive, pointing to past wins on counselors and class sizes. But he also promised a more assertive stance now that the SRC and its legal constraints are gone.

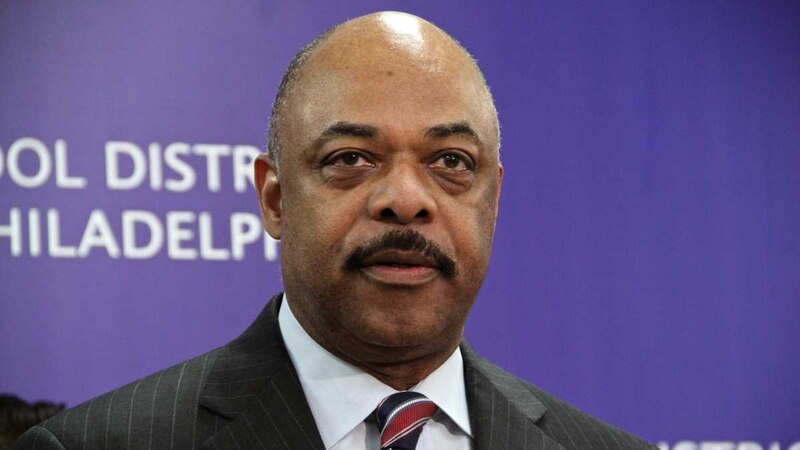

Jerry Jordan

Under his leadership, he said, the PFT will bring a broad set of contract demands to the table, seeking not only wage increases but also policy changes to address equity, safety, and working conditions.

“We have the right to bargain for more than wages and benefits,” said Jordan — which wasn’t the case under the state law that put the SRC in charge of the financially and academically floundering district in 2001.

He made the same point in a recent online chat with PFT members, stressing that unlike past years, “everything is on the table.”

In the chat, Jordan urged members to get involved and share their own proposals – a change from the last contract negotiation, he noted.

“Those of you who have been in the union for the past few contracts will notice a much higher level of member engagement activities in this negotiation process,” Jordan said.

During past negotiations, he said, there was little point in asking much from members, because of the SRC’s restrictions.

“We did not want to give the members the impression that we would be able to negotiate over something that the law said clearly we would not be able to negotiate over,” he told members.

But now, Jordan said, members should expect to play “an active role in shaping the provisions of our next contract,” he said.

This fall, Jordan’s team held six member meetings and conducted an online survey, seeking input on priorities for the next contract. In the online chat, Jordan promised members he would soon share some of those perspectives with the Board of Education; a PFT spokesperson said specific plans for that exchange have not yet been made.

In an interview, Jordan said he was hesitant to draw too many lessons from activism in Chicago and elsewhere, drawing a sharp contrast with the WE Caucus.

“Each city has its own culture and its own history,” he said.

But one of the strategies used in other cities that the PFT could embrace, Jordan said in the online chat, was that of allowing union members – not just leadership – to take an active part in negotiations.

“We have talked to our colleagues in Los Angeles and in Chicago who have talked about that strategy and how effective it was for them, so certainly it is something we will be looking at,” said Jordan.

The next steps

The WE Caucus has tried to win leadership positions before. Formed in 2014 to replicate the success of similar movements in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Milwaukee, it ran a slate in 2016 but was reportedly defeated by a 3-1 ratio. But Melville thinks the group’s steady, active presence in recent years will help put it over the top.

“We’ve done a tremendous amount of work since then,” said Melville.

She’s not entirely convinced by Jordan’s argument that state law that put the SRC in charge of the district, known as Act 46, is all that hindered the PFT from being more progressive. Jordan’s team was running the union “long before Act 46,” she said. But she sees the PFT’s plans to expand outreach and broaden demands as evidence that the national wave of teacher activism is already having an impact.

“The fact that they’re shifting in the direction that we’ve been going for five years says that it’s good to have these kinds of caucuses in place,” she said.

Jordan’s team, known as the Collective Bargaining Caucus, has not yet formally put forward a slate of candidates. But he said that he’s confident about his team’s record and its ability to build on past successes with issues such as class-size reduction and the expansion of counselors and nurses. Of his challengers, he said only: “They have a right to offer criticism.”

Melville is thrilled by the latest victories for common good-style candidates, including this week’s historic City Council victory by Kendra Brooks of the Working Families Party. She sees it as a sign that Philadelphia is ready for the kind of boundary-breaking activism in the education world that the WE Caucus bid represents.

Jordan is also pleased to see more potential allies in City Hall and elsewhere, but cautioned that contract talks will always be contentious – even with a mayor-appointed Board of Education that is presumably more friendly to the union than the state-imposed SRC ever was.

“It’s always a very difficult time,” he said. Regardless of who is running the District, he said, “It would be a mistake to assume that it will be easier.”