This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Updated 7/16/18: this article now uses per-pupil spending and revenue data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education, adjusted for local inflation and presented in 2018 dollars.

In the summer of 2012, Superintendent William Hite took charge of the Philadelphia School District. It was a year after Mayor Michael Nutter asked Superintendent Arlene Ackerman to resign after complaints about a lack of accountability over school violence and unethical contracting practices.

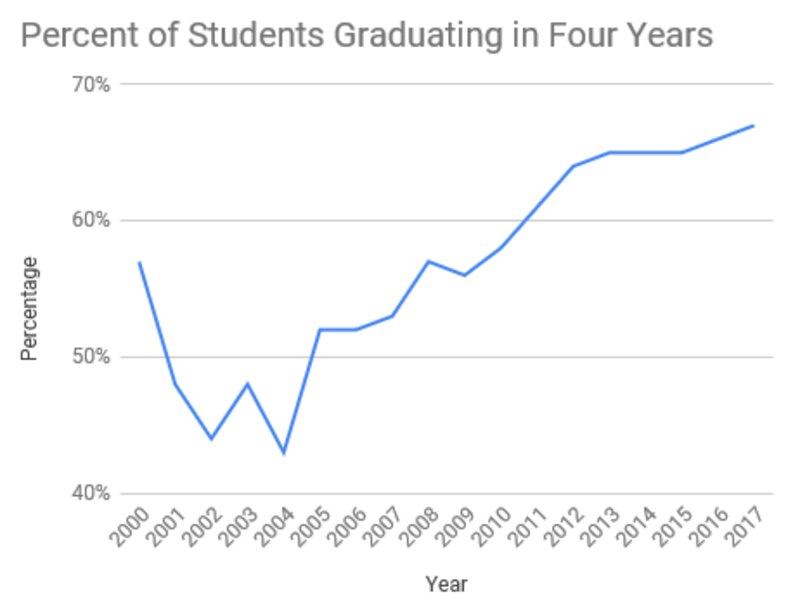

When Hite took over, he created Action Plans that set goals for the District. Action Plan 2.0, released in 2014, outlined a series of ambitious “anchor goals,” and in most areas, the District has made at least some progress: More high school students are graduating, more 8-year-olds are reading at grade level, and the District has balanced its budget.

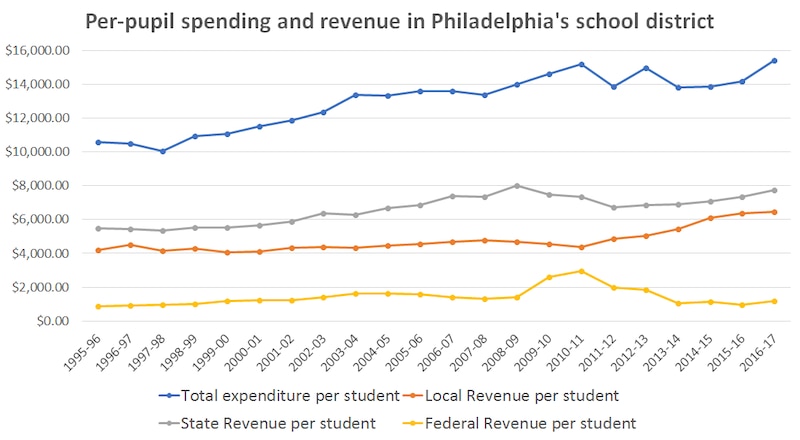

But this was at the tail end of the term of Republican Gov. Tom Corbett (2011-14), who cut roughly $1 billion in state funding for public schools, with hundreds of millions coming out of the District’s operating budget. So where did the District get the money it used to fund these goals and balance the budget?

Some came from the city, and when Gov. Wolf, a Democrat, was elected, he restored part of the state funding lost during the Corbett years. But it wasn’t until this year that Wolf even proposed enough additional education funding to restore the amount lost under Corbett.

Data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

While the District invested more in an effort to increase high school graduation and promote early childhood literacy, it was saving millions on labor costs in a contract stalemate with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers that resulted in its members getting no raises for five years. The District also saved money when it outsourced substitutes, although the original contract with the company Source4Teachers turned out to be a disaster that left schools far more in need of substitutes then under the old unionized system. The District has since hired another company, Kelly Services, which has improved the substitute fill-rate.

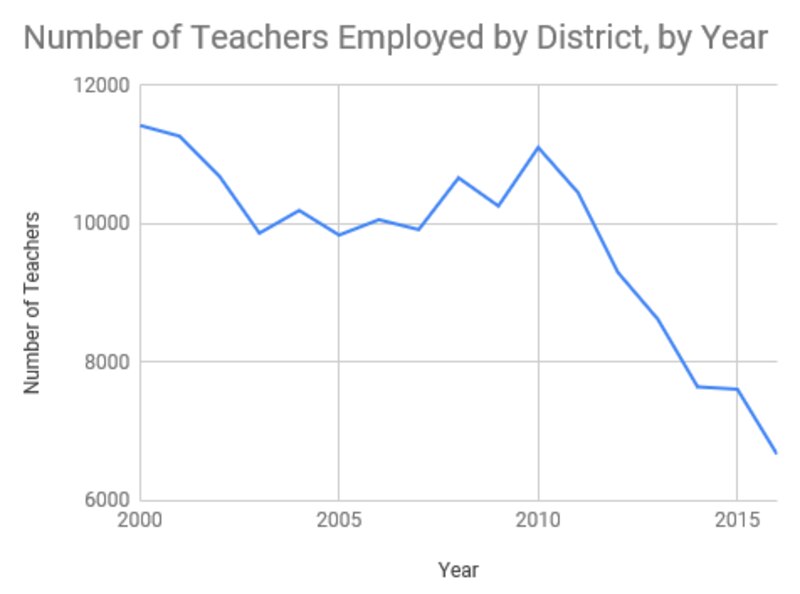

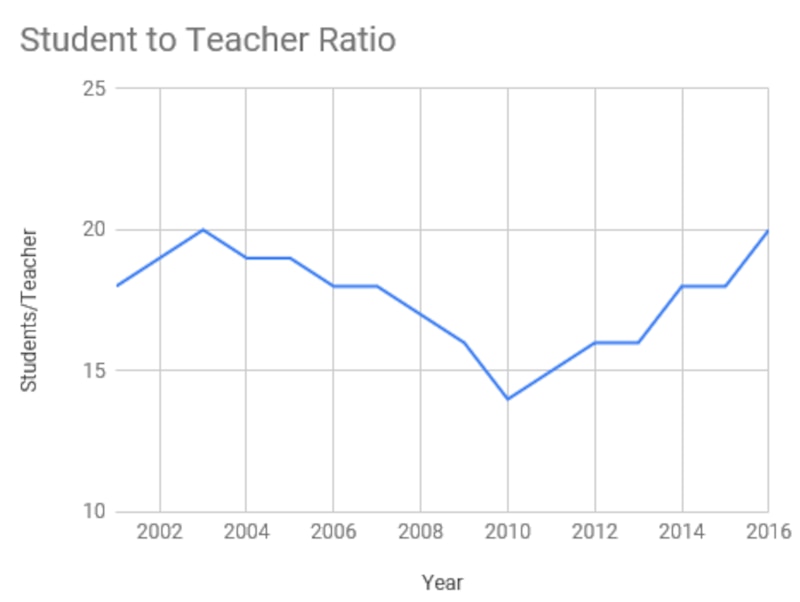

In the final year of the contract stalemate, the District said it had relatively few teacher vacancies. But the union pointed out that there were also 181 vacancies in support positions and conducted a survey finding that there were 613 classes with more students than the contractual limit, which depressed the actual teacher-vacancy count.

These practices made it hard, if not impossible, to reach another of the anchor goals: All schools having great principals and teachers. That’s not to disparage the teachers themselves, but working conditions depressed recruitment and affected the quality of instruction teachers could provide.

And these savings on labor costs came after the District closed a deficit in 2012, caused by Corbett’s state aid reductions. Nearly 5,000 positions were slashed, which was 25 percent of total staff positions at the time. This resulted in roughly 3,800 layoffs.

The same 2014 District document that outlines these layoffs, the Financial Supplement to Action Plan 2.0, describes saving money on labor costs as “paramount” to accomplishing the action plan’s goals. It took three years after that document was released for the teachers’ contract to be settled.

The goals related to labor, however subjective, do not seem to have been prioritized. Considering the lack of a teachers’ contract, it’s hard to imagine that the District was able to “improve recruitment and hiring practices to attract the highest quality candidates,” let alone “strengthen the principal and teacher pipelines.” The District did not “retain and promote high-performing staff,” because the lack of a contract made teachers unable to earn raises at all, let alone the promotions they were owed for earning higher credentials.

But Action Plan 2.0 had far more objectives than the ones labeled anchor goals. Most are vague and hard to quantify. But some can be measured objectively.

There are some that the District undoubtedly accomplished: improving student nutrition, reducing violent incidents in schools, promoting project-based learning and Career and Technical Education, creating and launching new school models, and implementing a new school evaluation measure in the form of School Progress Reports.

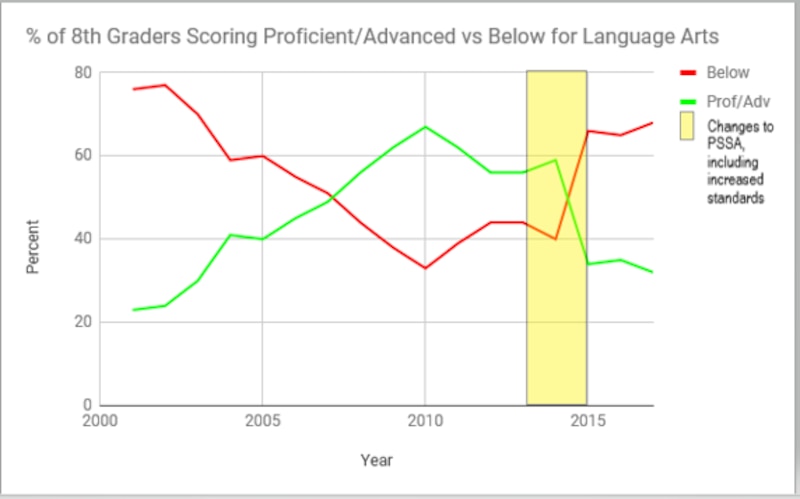

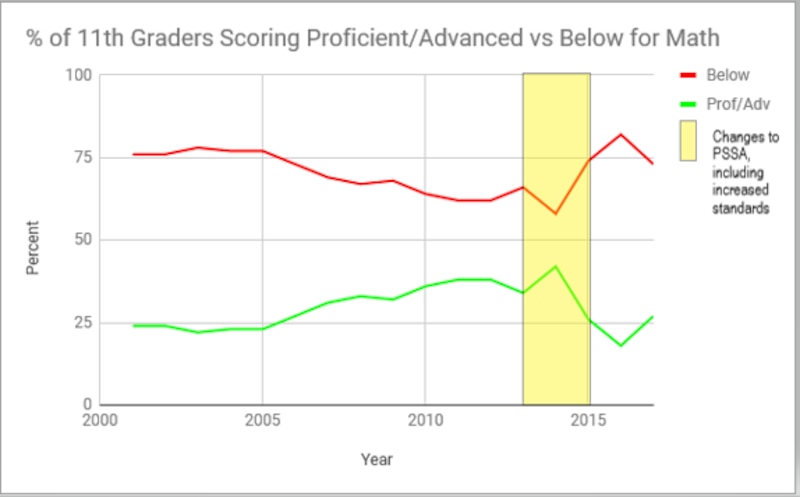

As the accompanying charts show, progress on standardized test scores increased under Gov. Ed Rendell (2002-10), roughly correlating with increases in state funding. These positive trends on the PSSAs reversed by 2012, roughly correlating to when Corbett began cutting state funding. The numbers seem to continue to decline, though some of this is because of the higher PSSA standards, implemented between 2013 and 2015, that made it more difficult to score proficient and easier to score below basic.

Since 2015, the year the standards were finalized and newly elected Gov. Wolf began restoring Philly’s education funding, PSSA scores either leveled off or improved slightly, depending on the grade and subject. Eleventh-grade reading and math scores improved the most.

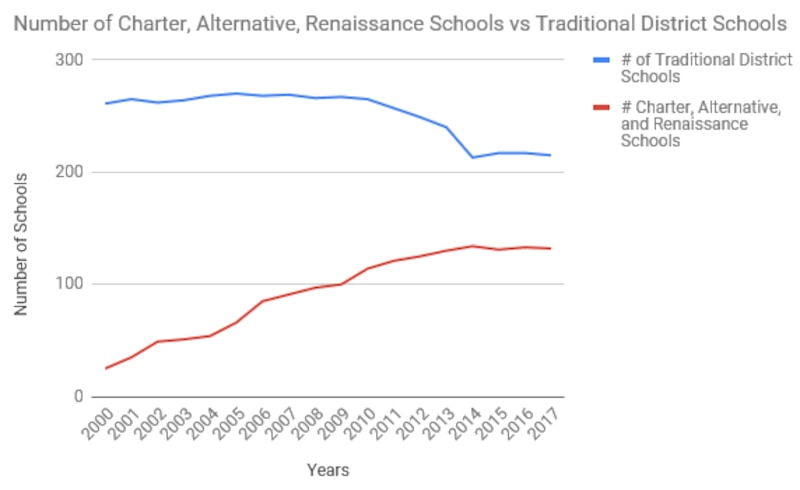

For a handful of goals, the District’s progress is debatable. One example is using the Renaissance school turnaround program to “make poor-performing schools better” by turning them over to charter operators while keeping their neighborhood catchment areas. The Renaissance program has not technically been abandoned, but it has been two years since the District used it.

Many of the Renaissance schools made initial gains, but then leveled off. In 2016, the SRC overruled Hite and awarded Wister Elementary in Germantown to Mastery Charter Schools, despite the fact that the school had made enough academic improvement that it did not qualify for turnaround. Wister’s School Progress Report rating under Mastery declined slightly the next year.

The SRC turned over 21 schools to charter operators through the Renaissance initiative, though since 2016 it has voted to close two of those schools due to questionable financial practices: Stetson and Olney, run by Aspira. The charter office also recommended the closure of Universal Vare, but the SRC last month renewed the school’s charter with conditions that include automatic charter surrender if it doesn’t meet stringent conditions after four years. Universal’s Audenried High School has also been recommended for non-renewal by the Charter Schools Office, but the SRC declined to take a vote.

Since 2016, the District has relied instead on internal turnaround models that don’t involve charter operators.

Another goal was to “ensure all charters are good school options.” Although the District has some high-performing charters, the SRC has lagged in pursuing closure recommendations from its charter office for any but the most egregiously poor-performing schools. A minority of Philadelphia’s charters received a passing academic score from the state, a point mentioned in the District’s Action Plan 2.0.

The explanation of that goal states the District will “actively seek the non-renewal and revocation of the lowest-performing charter schools.” The included financial document states that the District will “aggressively seek to close the lowest-performing charter schools.”

But the District has only closed a few charter schools in the years since. And dozens of charters are operating under expired contracts — a situation that would cause any other contractor receiving taxpayer dollars to cease operating.

These schools are allowed to continue collecting state funds as their dispute with the District over the terms of their operation remains unresolved. At its last meeting, the SRC only voted to close one charter school. Some others signed agreements after initially balking, but 25 continue to hold out.

In fact, another part of that goal was to “ensure all charter schools have signed charter agreements” – something that has clearly not been achieved.

Another goal was to “implement effective, aligned business processes.” But the District was recently sued by a bidder for arbitrarily awarding a contract to a favored company, and the District’s response to the lawsuit was to maintain that it has no obligation to follow city or state law or its own procurement procedures. The bidder has also filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education.

Another goal was to “provide a clean and comfortable building environment in all schools,” which would include “executing a more aggressive preventative maintenance plan.” The action plan cited research finding that students did better academically in buildings in “standard” rather than “poor” condition.

But since then, the District has found unsafe lead levels in at least one drinking water outlet at 53 percent of schools. After pushback from activists and community groups, the District arrived at a remediation process that involved faster testing, more thorough methodology, and the installation of filtered water fountains in every school. City Councilwoman Helen Gym’s office organized public hearings in Council on the issue and authored the legislation that Council ultimately passed.

The District also had mold outbreaks last summer, largely due to malfunctioning HVAC systems that caused excess humidity in school buildings, including Munoz-Marin and J.B. Kelly Elementary Schools.

All this prompted the Philly Healthy Schools Coalition, along with City Councilman Derek Green, to demand that the District publicly disclose its school-level environmental data on matters concerning public health.

Earlier this year, the District had to reboot a lead-paint stabilization project after the union’s environmental scientist found that workers were not fully cleaning up the dust left behind after sanding down the flaking paint. The project was started after a 6-year-old at Comly Elementary was found eating lead paint chips. The shoddy work wasn’t discovered until parents invited the union’s environmental scientist to inspect rooms at Jackson School. At that point, work was already underway in 16 other schools.

“Whether it’s lead paint or mold or asbestos, every month it feels like there’s another incident. Munoz-Marin in August, and then J.B. Kelly closes for a week, but those schools had problems for many years and the reaction was only triggered when some teacher posted something on Facebook,” said David Masur, director of Penn Environment that organizes the Health Schools Coalition. “Then you get Comly, and now Jackson. We shouldn’t be dealing with this like the Dutch boy putting his finger in the dam. We don’t have to live our lives this way.”

As a result, the District was called before City Council to explain how they would reform the process going forward to be more thorough in the scope of work and involve the community in advance as the project continues in the 46 schools needing stabilization.

A bill in City Council would require the District to make environmental test results publicly available and inform parents and community members in advance of such projects — the very thing that the Healthy Schools Coalition is demanding. It was introduced by Councilman Mark Squilla and is co-sponsored by Council members Derek Green, Helen Gym, Cindy Bass and Bobby Henon.

Wolf proposed that the state will split the cost of a $15 million emergency cleanup measure this summer that will remove asbestos, lead, mold, and other environmental hazards in 57 schools.

The District had a specific goal in skimping on maintenance. It ran up the deferred maintenance list to nearly $5 billion – though former City Controller Alan Butkovitz told City Council that his office found the real number to be $10 billion.

The District repairs its buildings by issuing bonds. But bond issues under Hite have been relatively austere, because one of the District’s highest priorities has been to earn a higher credit rating. It worked, saving the District money. The District did this by keeping annual debt service payments below 10 percent – in other words, by issuing fewer bonds each year to make repairs than were issued under previous administrations.

“We have to continue to balance the needs the District has for facilities investment with the need to not have our annual debt service cost eat up our annual operating [budget],” Uri Monson, chief financial officer for the District, told the Notebook last year.

Click for the full list of graphs and sources

Notebook interns Hannah Mellville, Sam Haut, and Alyssa Biederman compiled the data and graphs for this article.