This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

As City Council heard testimony Tuesday about Mayor Kenney’s proposal to generate nearly $800 million in additional funds over five years for schools in part by increasing property tax rates, a coalition of activists demanded measures that instead would raise revenue primarily from the wealthy and large nonprofits such as universities.

The Our City Our Schools Coalition was formed nearly a year ago by groups of activists, advocates, and labor unions who fought to bring an end to the School Reform Commission, which governs the District and is dominated by the state. Last fall, the mayor agreed that the District should return to local control and vowed to raise more city revenue to fund schools adequately and avoid constant cutbacks in programs and services.

But after Kenney announced his tax package in March, the coalition proposed raising funds in ways that don’t burden working and middle-class families. Primarily, it is calling for an end to the 10-year real estate tax abatement on new construction and want large tax-exempt institutions to make “payments in lieu of taxes” (PILOTs) to the city. Along with several other measures, the plan would raise over $250 million annually, the advocates say, more than the mayor’s package.

“We’re constantly told there’s no money for the schools our kids deserve — that there’s no funding to fix lead paint and mold,” said Antione Little, a Philadelphia parent and chair of the coalition. “But there’s plenty of money — it’s being hoarded by corporations, universities, and real estate developers. We’re calling on the mayor and City Council to force the wealthy of our city to truly pay up for our schools. Our schools can’t wait — and the working class of this city can’t afford yet another tax hike while the 1 percent remain protected by our elected officials.”

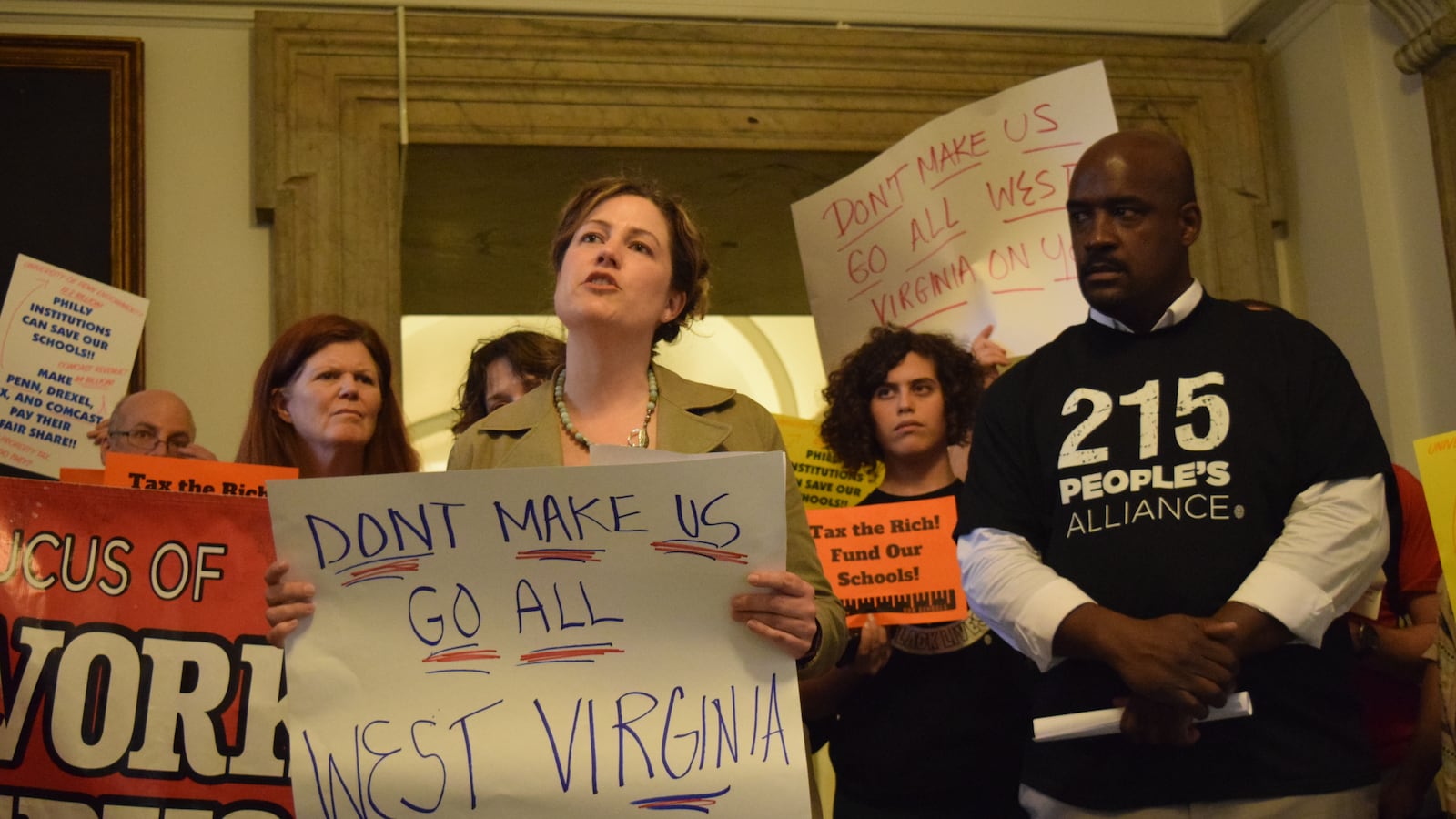

Red T-shirts dotted the crowd, worn by teachers with the Working Educators’ Caucus, which joined the coalition.

“Our schools are chronically underfunded and under-resourced, and there just aren’t enough staff to provide the support and guidance that our students deserve,” said Katrina Clark, a teacher at the Workshop School in Philadelphia. “At one school in my neighborhood, the kindergartners don’t have recess because there aren’t enough staff. We are sending our students to sit in rooms with active leaks, mold, rodents, and asbestos for seven hours a day. These schools are poisoning our children, and it’s time we do something about it.”

The thrust of the coalition’s ideas had support from former City Controller Alan Butkovitz, who testified during the hearing. Like the coalition, Butkovitz called out the new property tax increase and the existing tax abatement on new construction.

“In Philadelphia, consideration has been given to people who live in new construction to have 10-year tax abatements,” Butkovitz said. “And yet the people who live near new construction get hit with the burden of massive increases in [property] taxes.”

He was also “sickened” that Superintendent William Hite waited so long to ask the city for more money to repair facilities.

“When I was city controller – in conjunction with the teachers’ union – for 10 years, we pointed out the dangerous conditions of school buildings,” Butkovitz said. “At the time, we knew it would be a $7 billion rebuild.”

In an effort to make a start, his office and the union prioritized $50 million in emergency repairs and $1 million in “super emergency repairs” that required immediate attention, Butkovitz said.

“And we were met with the answer that they couldn’t find $1 million,” he said. “Now that we’re reading front-page articles about kids eating paint chips and losing the ability to do math in their head, now the School District says this is an emergency.”

Butkovitz called for the city controller to have the power to audit the School District, “just like they do with City Council.” The coalition is calling for an independent audit of District spending.

Earlier that day, Carla Pagan, executive director of the city’s Board of Revision of Taxes, mentioned that the District has begun appealing the property values of their buildings. These appeals assert that the current values of certain buildings are too low, indicating that the District intends to sell some property if the prices increase.

City Finance Director Rob Dubow outlined Kenney’s proposed changes to the city’s tax structure, which would raise $770 million over the next five fiscal years (2019-2023). This would cover the $660 million in additional funds the District needs over that time span to maintain current services and meet recurring obligations, while leaving an extra $110 million for new investments.

The money would be raised through an increase in the property tax, a cut in the rate at which the city is reducing the wage tax, and an increase in the tax on property sales.

“These new investments include expanding early literacy and providing more individualized student attention, putting greater resources in classrooms, and increasing resources for 21st-century high schools and [Career and Technical Education],” Dubow said. “While no one likes tax increases, the administration believes the investments in our future that this package would permit are worth the sacrifice.”

The coalition doesn’t oppose the entire tax package, but staunchly opposes the residential property tax increase, which Dubow said would generate nearly $200 million over five years. Instead, they said, their proposals would raise over $1 billion during the same time period.

The proposal would require massive nonprofits like universities and hospitals to make payments to the city in exchange for their tax-exempt status — something done by all Ivy League universities except the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia in New York City. It would also end the 10-year tax abatement on value generated through new construction or renovation, stop a coming decrease in the city’s business tax rate, and increase the Use and Occupancy Tax that applies to landlords of businesses.

It also calls for the creation of a public bank, which could provide an influx of cash to help with more than $4 billion in deferred maintenance costs across more than 200 District buildings.

“There are plenty of ways to fund our schools,” said Tonya Bah, a parent who was nominated for the nine-member Board of Education that will take over for the SRC in July, but not among the mayor’s final choices. She stood alongside fellow members of the coalition as she spoke. “We want City Council and the Mayor’s Office to know that it’s time for the rich to pay up, and we are done taxing working people.”

Shakeda Gaines, president of the Philadelphia Home & School Council and a member of the coalition, spoke about the stress of being a parent and the associated costs.

“Now imagine what it’s doing to our teachers who are paying for pencils and crayons,” she said, adding that the schools themselves are falling apart. “They expect them to teach under those conditions. … You expect our children to learn under those conditions and then wonder why they act like they act.”

Clark, the Workshop School teacher and member of the Working Educators’ Caucus, also spoke about those conditions.

“Imagine knowingly sending your child to sit in a room with active leaks, mold, rodents, and asbestos,” she said, adding that the temperature reaches 90 degrees on hot days and that there isn’t any money to replace the HVAC system in her building. “This means we have to wait for the money to have it replaced. When will this money come? When a child gets sick? When a child dies? When more students are chased out of the District into charter schools?

“What color should my students’ skin be in order to deserve a school free from leaks and mold? How much money should my students’ families make before they have a right not to breathe in air filled with roach feces?”

In the end, Clark’s message was simple: “Education costs money.”

“It’s past time to show our young people that they are our priority,” she said. “The only conscionable act is to fund our schools. Ethically. Equitably. Fully.”

Their message connected Philadelphia’s perennial shortfalls and Pennsylvania’s history of inadequate and inequitable school funding to statewide teacher strikes in states that, like Pennsylvania, have legislatures under Republican control. Many carried signs reading: #RedForEd.

“Our allies in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Colorado, Puerto Rico, and Arizona share the same feelings we have,” said Jessica Way, a core organizer with the Caucus and a teacher at Franklin Learning Center. “We have watched as our government starved our schools, then turned around and pointed out how deficient they were. I have also watched as my alma mater, the University of Pennsylvania, refuses to pay a dime for payment in lieu of taxes while turning around and asking if we would host their students as student teachers and nurses.

“Enough with the freebies and handouts. It is time for big business in Philadelphia to pay up, or it is time for us to force them to.”