This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

The shortage of substitute school nurses grew worse this year after the Philadelphia School District outsourced the service as a way to improve its historically low fill-rate for absences, according to data provided by the District.

Nurses say the situation was avoidable, likening it to the chaotic days in 2015-16 when the District first outsourced substitute teachers. They say the District learned little from that fiasco, when it hired Source4Teachers, a Cherry Hill-based firm that submitted the lowest bid but could not provide sufficient substitutes.

The District abandoned that contract and hired Kelly Educational Staffing, which was able to meet the terms of the contract and fill most of the vacancies.

After that success, it gave Kelly the substitute nurse contract in August. But the company has had a much harder time fulfilling that responsibility, leading the District to hire two additional firms whose focus is on health care rather than generic staffing.

“It will take some time for Kelly Services to recruit and build their nurse substitute pool, which is a priority focus,” said District spokesman Lee Whack.

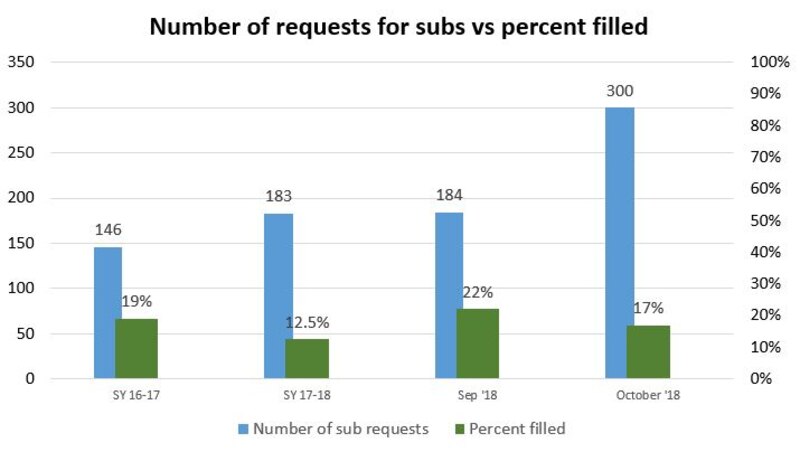

He said the number of substitute nurses placed each month has increased. But that has been outpaced by more requests for substitutes since the outsourcing. Overall, however, less than one in five absences is covered.

The nurses who are critical of the policy change say that the initial choice of provider was not the only misstep. The entire process was too last-minute, they said. The August start date for the contract left little time for the unionized substitutes to get the proper clearances and be hired by Kelly in time for the beginning of the school year.

“It’s a disgrace what they did,” said Peg Devine, who has been a school nurse since 1992 and is now on sabbatical from Lincoln High School. “It was very poor timing. It should have been done in June if they wanted to do this.”

Devine said the abrupt decision exacerbated the situation by reducing the number of former nurse substitutes who wanted to work under the new system at all.

Initial wages increased

As with the substitute teachers, the firms that were hired initially paid low hourly wages, only to increase them – and cut into the projected cost savings – as it became clear that the supply under those conditions would not meet the demand.

As of last week, Kelly has only been able to hire eight substitute nurses, many coming from the old unionized system. Others chose to retire due to the lower pay initially offered.

These substitutes were hired after the District agreed to increase the pay from roughly $25 to $34 an hour – comparable to substitute teachers. But that pay was only for the retired nurses who had worked as subs under the old system. One retired nurse substitute, who did not wish to give her name, said the increased pay changed her mind. She took the job.

Devine said the eight nurses hired under the new contract with Kelly are “certainly not enough,” estimating that at least 30 would be necessary to provide adequate coverage. Many school nurses’ jobs were eliminated in the draconian budget cuts made under former Republican Gov. Tom Corbett starting in 2011. Replenishing the supply has been an ongoing process since then.

“Once they increased the wage, they got some nurses hired, but they still said any new hires would get $25 an hour,” Devine said, calling the wage “absolutely not competitive” based on average wages for nurses in Philadelphia.

“We were told at the [Philadelphia Federation of Teachers] committee meeting that it would be upped to $34 an hour for everyone,” Devine said. “The next day, the woman from Kelly Services who works at 440 said she knew nothing about that, and it was still $25 an hour for new hires.”

School nurse Eileen Duffey said that $25 an hour is what she made working her first nursing job in the student health center at the University of Pennsylvania – and that was in 1994.

After nearly three months of difficulties, the District increased the wages for all substitute nurses on Monday, Nov. 5, although rates will differ depending on the agency they work for.

Substitutes hired by Kelly Services will now earn between $40 and $45 an hour, depending on experience and certifications. Those hired by the new firms will earn between $30 and $36 an hour.

Whack said the new wages are “more competitive” and should help with recruitment.

The three state contractors already providing substitute nurse services in Philadelphia to various state-run facilities pay between $34 and $47 an hour for weekday shifts. Bayada, one of the new contractors, will establish a new floor of $30 for substitute school nurses.

“Kelly Services is filling more jobs month over month this year than [the District] filled over the past two years,” Whack said. “Kelly is more equipped to recruit and manage a substitute workforce. They have three offices in Philadelphia dedicated to recruiting for [the District] with over 17 staff members and management.”

Access to medical records an issue

The contract has caused other conflicts with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. Originally, the substitute nurses did not have access to student medical records. The union’s committee that represents school nurses pushed back on the issue with the District, to no avail. So they decided to get the union’s lawyers involved, according to Devine.

Then, in October, Superintendent William Hite announced that this policy would be reversed at a Board of Education meeting, where several nurses, including Devine, were signed up to testify against the policy.

Devine is glad to have some of the outstanding issues resolved, but frustrated with the entire situation, which she called both “predictable” and “avoidable.”

An important District policy change last spring made the need for filling nurse vacancies even more critical.

The Nurse Practice Act mandates that school nurses distribute daily doses of medication to students. The District, like many others, was not strictly following that portion of the act. Devine said it used to be common for school principals to take written instructions from the nurse and distribute students’ daily dose of medication when the nurse was out.

Now the District is strictly following the act and no longer allows this, a move that Devine applauded. But she said that made the need for more substitutes this school year entirely predictable, raising questions about the District’s decision to enforce the medication policy and outsource substitute services at the same time.

“This absolutely caused an increased need for nurse coverages,” Devine said. “Even if nothing had changed, to do this at such a late time in the summer was totally irresponsible.”

Duffey agreed.

“Starting this September, they knew they would expect us to tighten our ship and follow the act,” Duffey said. “That should have told them that they needed a ton of extra nurses for substitutes.”

Building on an informal “buddy” system that the nurses devised themselves, the District created cohorts of five or six schools that are close together. A nurse at one of the schools could be called upon to go to one of the other schools to administer medication for an absent colleague. The system is necessary because most school nurse absences still go uncovered by a substitute.

Duffey would prefer the District build a larger in-house unit of substitute nurses.

“Back in the day, it used to be that way, and it always worked,” Duffey said. “Even if they had to pull you to another school, they never yanked you and expected you to be in two schools in one day’s time.”

The two firms hired by the District to supplement Kelly in providing substitute nurses are Bayada Home Health and Maxim Healthcare Services.

Bayada got its first contract in Pennsylvania in 2009 to provide per diem nurses to the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs. The company has also contracted for Cheyney University to help staff student health centers. Those contracts have since expired.

Both are part of a massive $1 million annual contract for multiple companies, renewed every five years, to provide substitute nursing services to all state agencies that provide nurses. That includes state hospitals, the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Human Services – responsible for Youth Development Centers.

School nurses reached for this story said they understood the bind that the School District was in, but didn’t feel that the new system is a real solution to the problems, but rather just another way to save money.

“Here’s the problem. I don’t know the solution,” Duffey said. “Those eight substitute nurses, they can work for whoever they want. They don’t sign on and have to work any difficult assignments. They choose.”

Whack said the District is aware of this, but “we coordinate with Kelly Services to provide incentives to pick up jobs in hard-to-fill or critical situations.”

“This cash-strapped system is always going to be fighting how much it will cost to do this,” Duffey said. “But always having a nurse in the building really matters.”