This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

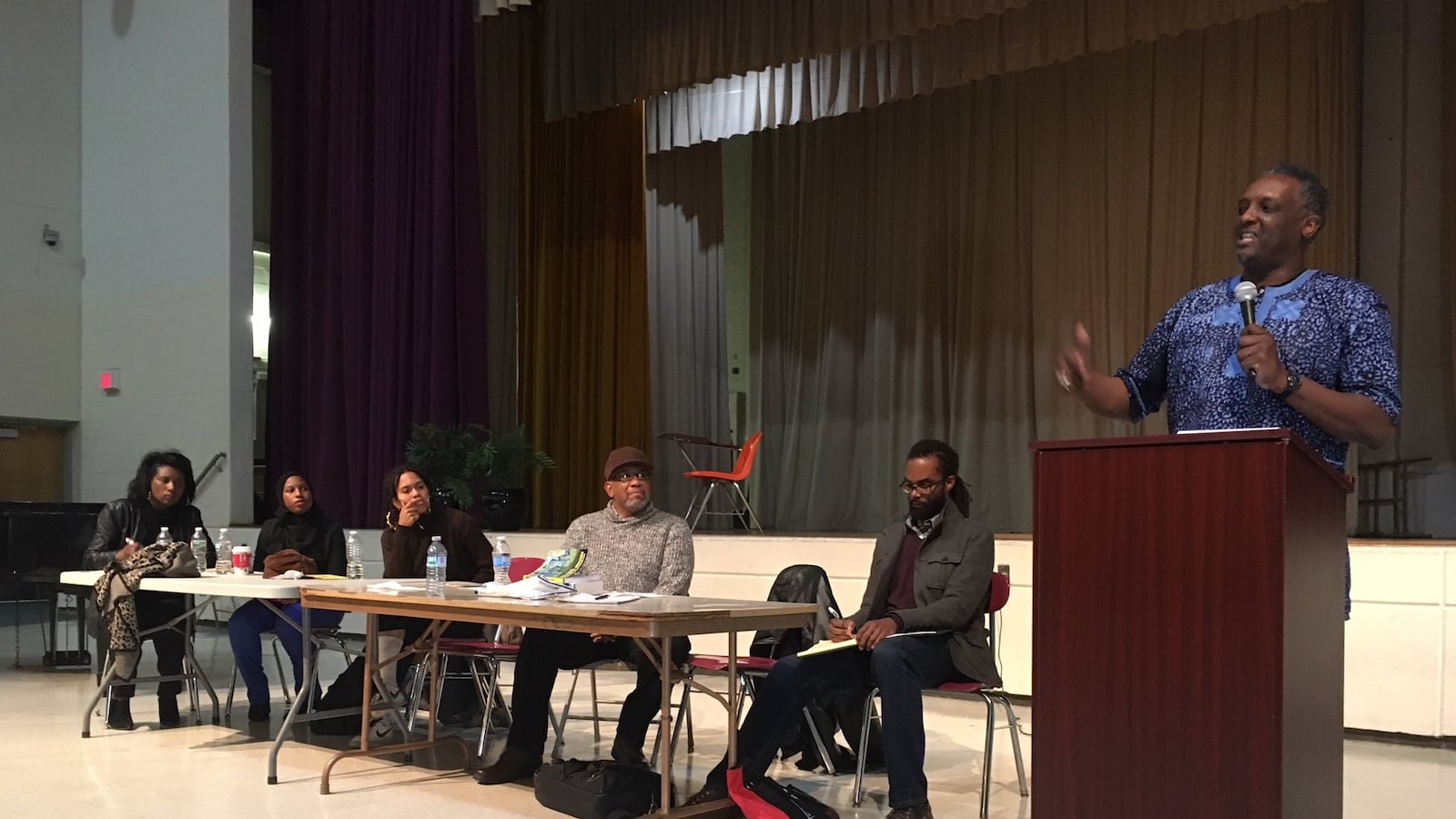

Notebook file photo

A three-day commemoration of the 50th anniversary of a student walkout brought together student activists of the past and those of the present, along with scholars and politicians, to learn from history and chart a course for the future in a school district still plagued by racial inequality.

The events started Thursday with a proclamation by City Council. They continued with a panel discussion Friday and concluded Saturday with a teach-in.

“There are moments in time when the past meets the present in incredibly powerful ways,” said City Councilwoman Helen Gym, who, with several of her colleagues, sponsored the proclamation and helped arrange a panel discussion on Friday night at the African American Museum of Philadelphia.

On Nov. 17, 1967, between 3,500 and 4,000 students walked out of their schools and converged on the Board of Education building at 21st Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway. They demanded more courses about African history and African American history in the curriculum, more black teachers and principals, more say in school governance, official recognition of black student groups, the right to wear dashikis and other African garb, and the right to refuse to salute the flag.

But while their leaders were meeting with Superintendent Mark Shedd and Board of Education President Richardson Dilworth, police in riot gear under the command of then-Commissioner Frank Rizzo arrived and started beating them up.

The walkout occurred during the height of the civil rights era and Black Power movement and three years after riots destroyed the heart of the commercial district in North Philadelphia.

“I like to say I grew up knowing I would tell this story,” said Matthew Countryman, associate professor of history at the University of Michigan, whose 2006 book on the civil rights struggle in Philadelphia, Up South, has a whole chapter on the incident. He delivered the keynote address at the Friday night discussion.

Countryman is the son of Joan Countryman, a longtime Philadelphia educator who was inside the Board of Education headquarters during the walkout. His grandfather was a counselor at Gratz High School who, in 1939, became the first African American ever appointed to a teaching job in a Philadelphia high school.

“Social movements are where people learn how the world really works and how they can change the world,” Countryman said. The walkout “was a culmination of 30 years of advocacy for teaching black history and 20 years of activism in Philadelphia.”

“The march was not spontaneous. It took months of planning,” he said. Groups like the Black People’s Unity Movement helped organize it.

The 50th-anniversary commemorative events started on the same day that the School Reform Commission voted to disband and return the School District to local control after 16 years of state dominance, a coincidence that drove home the need for continued activism.

“To think about the connection between those histories and this present is to really plead for us to tell our stories. … Storytelling plays an important role,” Countryman said.

Mary Seymour drove up from Atlanta to tell her story – of growing up near Broad Street and Columbia Avenue in North Philadelphia, attending public schools, and living through the 1964 riot, which decimated her community.

“There were no supermarkets, laundries, cleaners, drugstores. Nobody came back,” Seymour said. “It was ripe for a situation like Frank Rizzo.”

The Black Panthers, she said, organized in response to police misconduct, and they dispensed food and schoolbooks and helped with homework, in addition to telling young people they had the right to protect themselves from the police.

Portraying the Panthers as simply a violent organization “was the original fake news,” she said.

Seymour was a student at Community College of Philadelphia at the time of the walkout, but she had attended Gratz and helped organize the action. She was at the march herself.

It was peaceful, she said. Many of her friends were inside talking to District officials about their demands, when “all of a sudden there was Frank Rizzo. All these police officers in riot gear, wearing visors.”

She came face-to-face with Rizzo and his “storm troopers,” Seymour said. “I remember him saying, ‘Get their black asses.’” She ran for her life away from a policeman chasing her. His eyes had gone cold, she said.

She fell against a fence and a baton came down on her head, leaving a scar that still remains.

“I find students and teachers who are still struggling with some of the very same things we struggled with 50 years ago,” she said. She urged continued activism. “You shouldn’t think someone else will do it, you have to do it.”

During the panel discussion that brought together activists from 50 years ago and from now, Shania Morris of the Philadelphia Student Union said that she had started organizing at age 13. “I saw injustices inside my middle school, and knew something was wrong inside my school and neighborhood.”

The youth of today may have different ways or organizing and mobilizing youth than the elders, she said, “but we need support, not to be judged. We’re really into using art and helping young people to learn to express themselves. They feel they don’t have a voice.”

On Saturday, teacher activists sponsored a teach-in at Martin Luther King High School.

It was hosted by Kensington CAPA teacher Ismael Jimenez and moderated by Edward Onaci, an assistant professor of history at Ursinus College. Panelists included Muhammad Ahmad (formerly known as Max Stanford), a civil rights activist and co-founder of Revolutionary Action Movement; Greg Carr, associate professor of Africana Studies at Howard University; and Dana King, former African American curriculum specialist for the Philadelphia School District, who helped create the curriculum for the District’s African American studies course.

An audience of about 50 people was treated to a history lesson on Philadelphia’s civil rights activism and the importance of teaching African American studies, one of the biggest demands of the protest. For much of the discussion, Ahmad and the elders of the panel shared their journeys in activism during the 1960s.

“I think what 1967 says is that when young people decide that they’re going to leave their classrooms and go out and march against the District because of the education injustices,” said King, “we need to continue to instill this in our children in and outside of the classroom.”

Ahmad, a former professor at Temple University, worked with notable civil rights leaders such as Malcolm X, John Henrik Clarke, an African history scholar; Jesse Gray, a New York activist; and Amiri Baraka, a poet and scholar.

At the time, Ahmad was one of many activists surveilled by the Counterintelligence Program, a division of the FBI that tracked domestic organizations and leaders deemed to be a threat.

Now in his 70s, the activist and educator chronicled his time with groups such as the Black Panthers and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and talked about how they related to each other to illustrate that events like the 1967 student walkout were part of a greater movement for justice. Ahmad’s organization worked to educate and unite African American communities through local outreach, inspiring activism among black youth and instilling a sense of identity.

“A lot of what looks separated is not separated at all,” he said.

After the 1967 march, some schools and local organizations began to teach or incorporate African American history into their programming and curriculum, but no immediate results were seen districtwide. However, in the decades that followed, young activists took note and drew inspiration for their own movements.

Hiram Rivera, former executive director of Philadelphia Student Union, said a walkout in May 2013 that PSU helped organize was inspired by the 1967 walkout. To protest school closures and funding cuts, 3,000 students marched without incident from School District headquarters, on Broad Street, to City Hall.

“What the walkout did in 2013, just like it did in 1967, was it gave an opportunity for students who had never been involved before politically, who never been engaged in social justice work prior to that time, a moment to step in,” said Rivera.

“A moment to have their voice heard, to engage for the first time. They found their space and their voice for the first time. [It was] a moment to enact leadership and do so in a way that was going to capture the attention of the folks in power to let them know that you cannot continue to make decisions that do not include young people.”

It wasn’t until 2005 that African American studies became mandatory in the District for students to graduate, and that is revered as a milestone moment in Philadelphia’s black history. But there are still challenges to properly teaching the material. It isn’t a typical narrative that starts with slavery and ends with the civil rights movement, and some teachers simply don’t put in the effort needed for the course to be effective.

“I’ve seen that a lot of other teachers don’t care about African American history. [To them] it’s the easy course to teach,” said panelist Keziah Ridgeway, a history teacher at Northeast High School.

Some teachers who teach the class don’t bother to go beyond slavery, she said, which puts into children’s minds “that your history starts with being a slave and that’s all you’ll ever be.”