This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

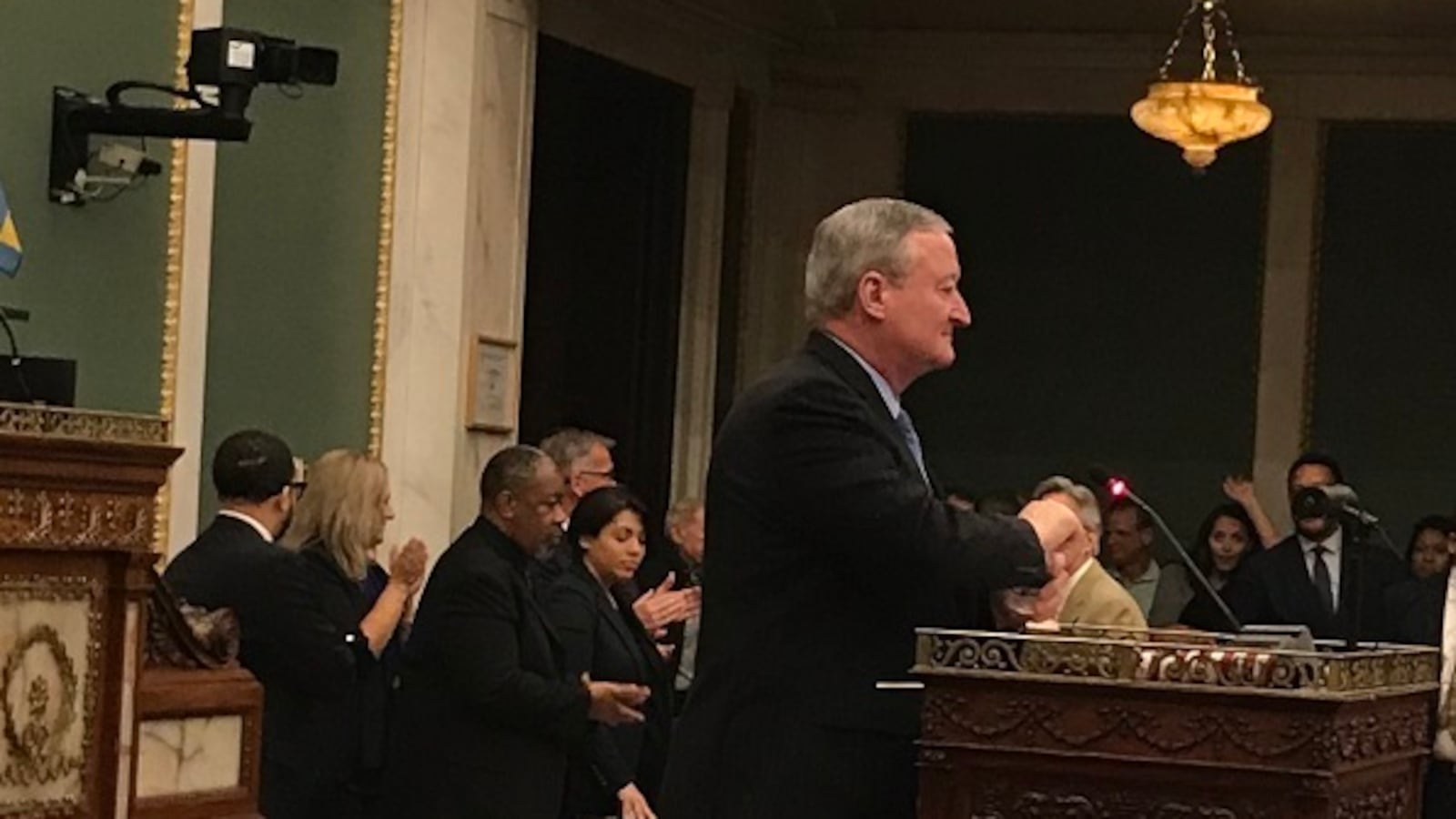

In a fervent speech to City Council on Thursday morning, Mayor Kenney declared that Philadelphia must take back control of its schools – and boost its investment in education – so that the city can break the cycle of poverty and shape its future.

The SRC was formed in December 2001 as part of a deal between city and state officials. City officials needed more money for the beleaguered school system. State officials wanted greater say in how the system operated.

Kenney made the case that there is no benefit to keeping the School Reform Commission in power any longer, saying that additional financial help from a politically divided and tax-averse General Assembly is “highly unlikely.”

“No matter how anyone may feel about it, that’s the reality,” he told a packed Council chamber, dotted with former SRC members as well as activists who have repeatedly demanded the end of a commission that they consider unrepresentative and unresponsive. “To say otherwise, we would only push off the responsibility we all say we want with local control.”

Kenney did not propose any new local revenue sources for the District, although he listed several sources that he said would not do the trick: improving collection of delinquent taxes ($600 million in new money is already budgeted), getting “payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTS)” from huge nonprofit institutions such as universities and hospitals, and increased money from recent cigarette and sales tax boosts designated for the District.

Kenney never mentioned the word tax. The closest he came: “The final plan we will propose to meet the District’s needs will be difficult, and it will require everyone to pitch in – but the alternative is far worse. … We must choose this moment and become the masters of our own destiny. If we pair local control with increased investments, we can finally confront our city’s most persistent challenge.”

The next six months of this transition of power are likely to be filled with battles over new taxes and over who will be on the new nine-member Board of Education that would take over governance of the School District on July 1.

Activists who had pushed for the SRC’s dissolution were pleased with Kenney’s action, but some called for an elected board, not an appointed one.

“We applaud the mayor for the great thing he’s doing, taking ownership and accountability of our schools,” said Sheila Armstrong, an organizer with POWER, an interfaith organization that belongs to the coalition Our City, Our Schools. “But we want to also ensure that the people’s voice is being heard.”

Kenney outlined the process for naming a 13-member nominating committee that will give him three names for each of the nine seats.

City Council introduced a resolution Thursday to amend the city charter so that the mayor’s nominees will need approval from Council. After hearings on that resolution, Council is likely to pass it before the end of the year. The School Reform Commission will vote at its next meeting, Nov. 16, on a resolution to dissolve itself. The resolution is expected to pass; at least three of its five members have said they favor it.

“Strong public education is the most significant factor in the welfare of our city and the future of our children,” said SRC Chair Joyce Wilkerson in a statement. “It is time for Philadelphia to take ownership of that future.”

As far as new city revenues, reaction from City Council members indicated that it will not be an easy sell to, say, raise property taxes, which are the largest source of local dollars for the District.

“You must be new here,” Council President Darrell Clarke said to a reporter who asked him whether he was open to raising taxes to fund the schools. “I never answer a question about taxes until I have to vote. There is a process.”

That process, he said, involved putting together a budget first and then deciding how to pay for it. Still, Clarke said, “This is a very significant day.”

Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sanchez said that Kenney “is committed to education and he stuck his whole political equity behind it. And now we look forward to his financial plan.”

Sanchez emphasized something that the mayor downplayed: the state’s constitutional responsibility to assure adequate funding and equitable distribution of its education dollars. Pennsylvania is one of the stingiest states in the country in paying its share of total education costs; it pays around 35 percent, and the national average is close to 50 percent. That puts more burden on local taxpayers and exacerbates inequities due to districts’ wealth.

In September, the state Supreme Court agreed to hear the merits of a school funding case brought by several parents and school districts.

“There’s a whole process that’s going on through the courts around designing a funding formula that really does hold the state to its responsibility,” Sanchez said in an interview.

She also stressed the need for the School District to be more transparent about its spending, mentioning legal fees as one area that Council wants to learn more about.

Still, she said, “everything has to be on the table” in the search for more revenue for schools.

“We’ve done commercial lien sales, PILOTS, everything has to be on the table,” she said, including “performance-based budgeting” and other areas to find savings.

“We know there’s going to be a $1 billion deficit. You need a plan for that,” she said. “But before we can tell people we’re going to dig into their pocket, we have to show them that we are being transparent and accountable.”

Although the District has been running a small fund balance for the last three years, it forecasts a shortfall of more than $900 million by 2022. The city has stepped up its local contribution over the last several years as state increases to District coffers have stagnated.

Last year, Harrisburg came up with a funding formula based on actual enrollment and District needs, but then decided to apply it only to a tiny portion of education aid. If the formula were applied to all education aid, Philadelphia would reap an additional $300 million a year – enough to close the budget gap.

Kenney said that his goal is to have high-quality schools in every neighborhood.

“Without them, the people who have helped to reverse the city’s decades of population loss will not stay; the children whose families cannot afford to leave will be unprepared to compete in the 21st-century economy; businesses will not come to Philadelphia, and those that are here won’t have the local talent pool to grow; and the city’s poverty and crime rates will remain stagnant or worsen,” he said.

The mayor warned: “If we do not provide our children the resources they need, the cycle of budget cuts and instability which have hindered our students’ success for decades will continue. And Philadelphia will slowly, but surely, fail. That’s a dark prediction, but it’s an accurate one.”

One person who was visibly hailing the development was Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

“This has been a long time coming. We’re very happy the mayor is taking a positive route to local control. State takeovers have no history of working anywhere in this country,” Jordan said.

As far as raising local taxes, he said: “The mayor said raising taxes is on the table. I take that as him being honest, as opposed to it being a given.”

PFT members went five years without a contract due to a stalemate between the SRC and the union, finally reaching an agreement last year.

Kenney indicated that he is pleased with the District’s current leader, Superintendent William Hite, hailing both stability and accomplishments under his tenure. Those he cited included improvements in early literacy, a slight uptick in test scores, additional reading coaches and classroom libraries in grades K-3, higher graduation rates, modernized career and technical education programs, free SAT and PSAT administrations that allow more students to take the college-entrance tests, and the hiring of more bilingual counseling assistants. Other notable statistics are the reduction of school-based arrests by 70 percent and the elimination of any school being listed as “persistently dangerous.”

Increased coordination with city agencies can also lead to better transportation, career readiness, job placement, and social services, Kenney said.

That process is likely to prove contentious as different groups vie for representation.

Clarke said that he wants Board of Education members to be representative of the city demographically, but he opposes electing the members, fearing that “special interests will dominate.”

But some activists say that is not a reason to avoid a democratic process.

“I don’t think the answer to having problems with the electoral system and outside money is to not hold elections,” said Lisa Haver, a retired teacher who is a co-founder of Alliance for Philadelphia Public Schools. “Should we appoint every member of City Council, too? The same argument could apply. How far are we going with this?

“The answer to that is: Let’s look at the campaign finance laws and do something about stopping dark money, but the answer is not taking away your right to vote or saying we’re not going to give you the right to vote at all.”

Other activists reiterated concern about who gets to be on the board, regardless of how they are chosen.

“I’d like to see the board made up of stakeholders that have skin in the game, and that is actual Philadelphians who send their kids to school here,” said Tonya Bah, a parent activist with two children in city schools. “I’m nervous in the pit of my stomach. I want to believe that this process could be done with fidelity. And if they are appointed, I want to see true stakeholders like parents from the community and not people tied to elected politicians.”

Another issue is how the charter school community is represented; about one-third of the children in publicly funded Philadelphia schools attend charter schools.

“I’m glad he said it will be painful,” said Sharif El-Mekki of the mayor. El-Mekki is principal of Mastery Charter School at Shoemaker and a former District teacher and principal. “Because some people think it’s going to be a panacea. Oh, as long as the SRC is gone, all the problems are fixed.”

But he asked: “How were black and brown kids faring before the SRC was implemented?”

El-Mekki said he appreciated Kenney’s assumption of responsibility.

“Folks always demand more money. People don’t always demand personal responsibility to educate black and brown children. So let’s put our money where our mouth is.”

Kenney went off-script at the end of his speech to say what he foresees for children entering the Philadelphia schools now.

“I have a vision of a child that is leaving a quality pre-K in June and entering kindergarten in September who is prepared to progress through 8th grade and do well, and then make a choice to go to a regular high school, an accelerated high school, CTE school, and do well there. And then have the opportunity to go to college or to graduate school.

“And that if companies like Amazon or others come into our city – and it doesn’t have just be Amazon, it could be any of the companies we attract – if that child, if that young man or woman, now graduating from college or from graduate school, can accept a job for $75, $80, $100,000 and be able to raise a family if they choose, to buy a home in our neighborhoods, to make our neighborhoods stable, and to make sure, to ensure, that their children, their children’s children, for generations, will not be facing poverty and opioid addiction and gun violence and crime, but will be able to do the things that our parents all wanted us to do and have a better life than we have. We owe it to those kids, and we will do this together.”

WHYY News reporter Avi-Wolfman Arent and Notebook freelance reporter Greg Windle contributed to this article.