This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

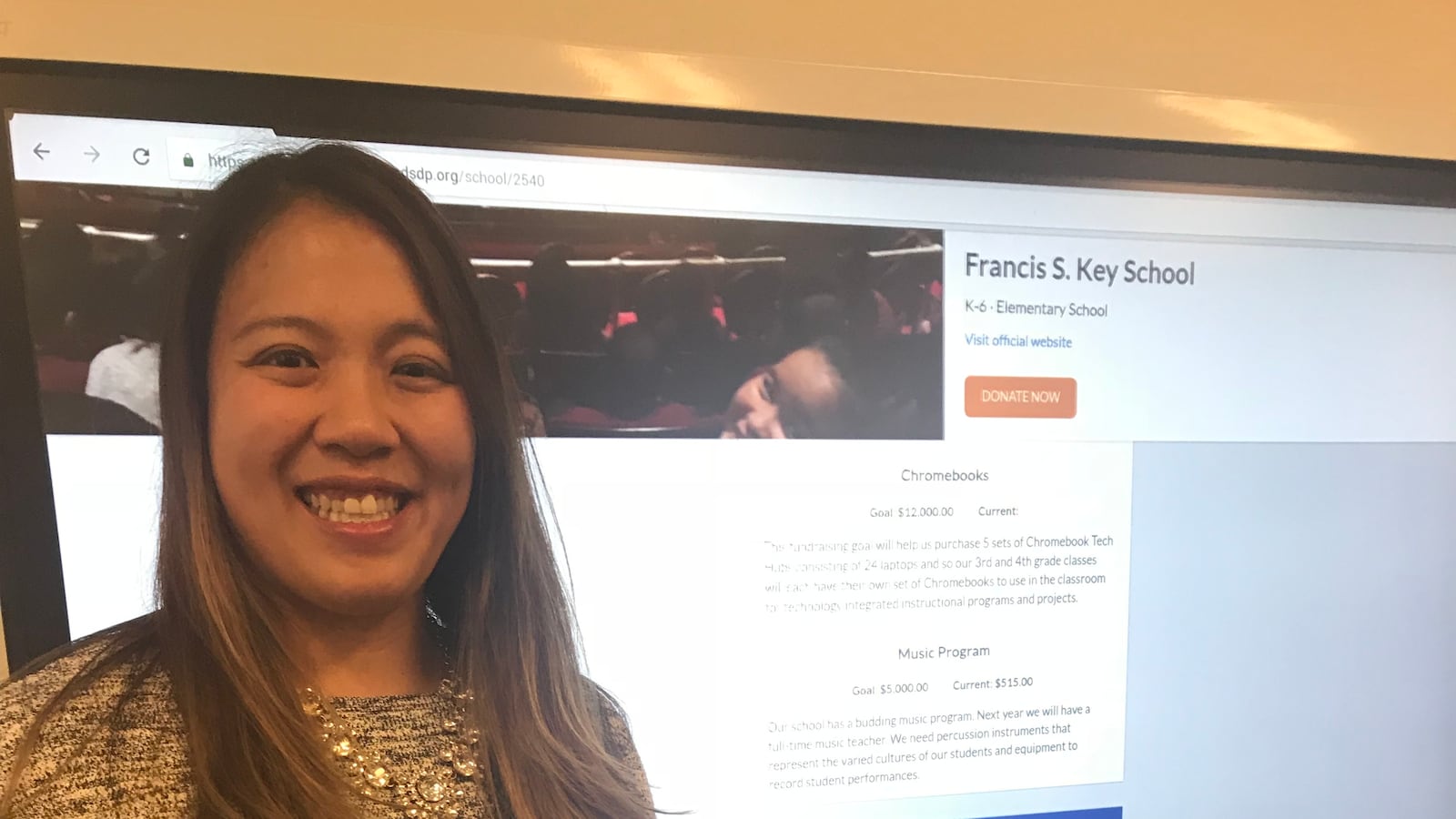

Pauline Cheung is principal of Francis Scott Key Elementary School in South Philadelphia, which is housed in a building that dates to the presidency of Chester Arthur (1881-1885). But it still reverberates daily with the sound of 500 K-6 students, many of whom come from families from such places as Nepal and Burma and Mexico. Collectively, the students speak more than 20 languages, and half are still learning English. Her heart’s desire is a library with children’s books from her students’ countries and cultures – not just written in their home languages, but also telling stories "that reflect their experiences and journeys," as she put it. "Some grew up in refugee camps," she said. She is seeking $15,000 for this project. Chueng was one of several principals attending the kickoff of a new initiative of the Fund for the School District of Philadelphia called Philly FUNDamentals, which allows potential donors to find a school and a project that appeals to them so they can contribute to it directly. "Our future depends on a highly educated workforce," said Mayor Kenney at the event launching the new site. "It is important to be as resourceful and creative as possible to make sure we are supporting every single student and every single school. Philly FUNDamentals is an ingenious tool." Talking later to reporters, Kenney seemed to give a small preview of what he will say in a major speech scheduled for tomorrow on education policy. "The most important thing we can do as a city is educate our children," he said. Education is "the most important service that government provides. And we talk about crime and we talk about lots of things; if we fix education, all those other miseries that we deal with subside." Donna Frisby-Greenwood, president and CEO of the District’s fundraising arm, said that in two years of consulting the community through focus groups and other means, "what we heard over and over … is that [people] wanted a way to help schools directly. They had heard that schools needed small things and they wanted a direct way to do it. But they didn’t know how to get in touch with schools." The idea was born to build an online platform that maps all the schools in the city. Users can filter the schools in a variety of ways – by neighborhood, by school level, by type of school – for instance, if it is a community school or undergoing a redesign or a turnaround. Or, the potential donor can just go straight to the school itself. Each page has the name and a picture of the principal and a list of one to three projects and their costs. Although there is no total of all the projects, 220 schools are participating and some donations have already been made. The Development Workshop, a group that includes economists and architects as well as developers interested in promoting economic growth in the city, has chosen five projects in five different schools and is in the process of raising $25,000 to fund them. They include an attendance incentive program at J.B. Kelly Elementary in Germantown and a divider in the James R. Lowell Elementary multipurpose room to separate the cafeteria from the gym area. David W. Feldman, president of Right-Sized Homes, which is part of the Development Workshop, said the group sought out schools in neighborhoods "where not a lot of development was happening" and schools that didn’t already have visible partnerships with local organizations. "Our members are aware of those neighborhoods, which are not where they’re working," he said. "We understand that those neighborhoods have needs." Cheung, the Key principal, has two other items on her wish list besides the multilingual library: new Chromebooks and money for percussion instruments for the school’s rebuilt music program. For several years, the school went without a music program. "Many of our computers are 2008 Apple desktops," she said. The laptops are also outdated and teachers must move them from classroom to classroom on carts in the vintage building with no elevators. "We need more laptops," she said. "It’s tough with those carts." Gina Hubbard, principal of Greenberg School, was at the event to highlight what she would like for her school, which is in a relatively affluent section of the Far Northeast. Greenberg was not insulated from the District’s overall money woes, and Hubbard said the school still faces important needs for a rapidly changing student body. "We have kids from all backgrounds," said Hubbard, who has led the school for 13 years. "Everything changes. We have a lot of needs." Greenberg, which stages plays and musicals, would like $10,000 to replace ancient drapes on its stage, and eventually to replace the floor on the stage. Like most buildings in the District, it has issues relating to a facilities budget that doesn’t always allow for necessary updates and repairs. "We have to make sure our students and teachers have a safe environment," she said. Kenney is expected Thursday to launch an effort to return the District to local control. He noted in his brief remarks that the District had been forced to slash personnel and resources over several years after state budget cuts. Many schools were left without nurses, counselors, music and art teachers, or even basic supplies. "We are on the cusp of a new era in Philadelphia education," Kenney said. "We are never going back to the cutting days again. Ever." He blamed inadequate education for the unending cycle of intergenerational poverty and vowed to break it. "We are not going to subject another generation to poverty," he said. Philadelphia has the highest poverty rate –26 percent – among the country’s 10 largest cities. After the event, he told reporters that Philly FUNDamentals connects more people and communities to needs of the schools, and not just those in their own neighborhoods, which is crucial. Affluent communities, like those on the Main Line, he said, can raise money themselves, but "we have schools that are in very poor neighborhoods, and parents struggle with resources. When you’re living in a struggling neighborhood with high unemployment, it’s hard to get the resources from the school family." Although the School District is in a period of fiscal stability and running a small surplus, it is forecasting a shortfall in excess of $900 million by 2022. Kenney, however, vowed that "we’re not going back to the bad old days of making that poor guy, Dr. Hite, have to cut and cut and cut."