This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

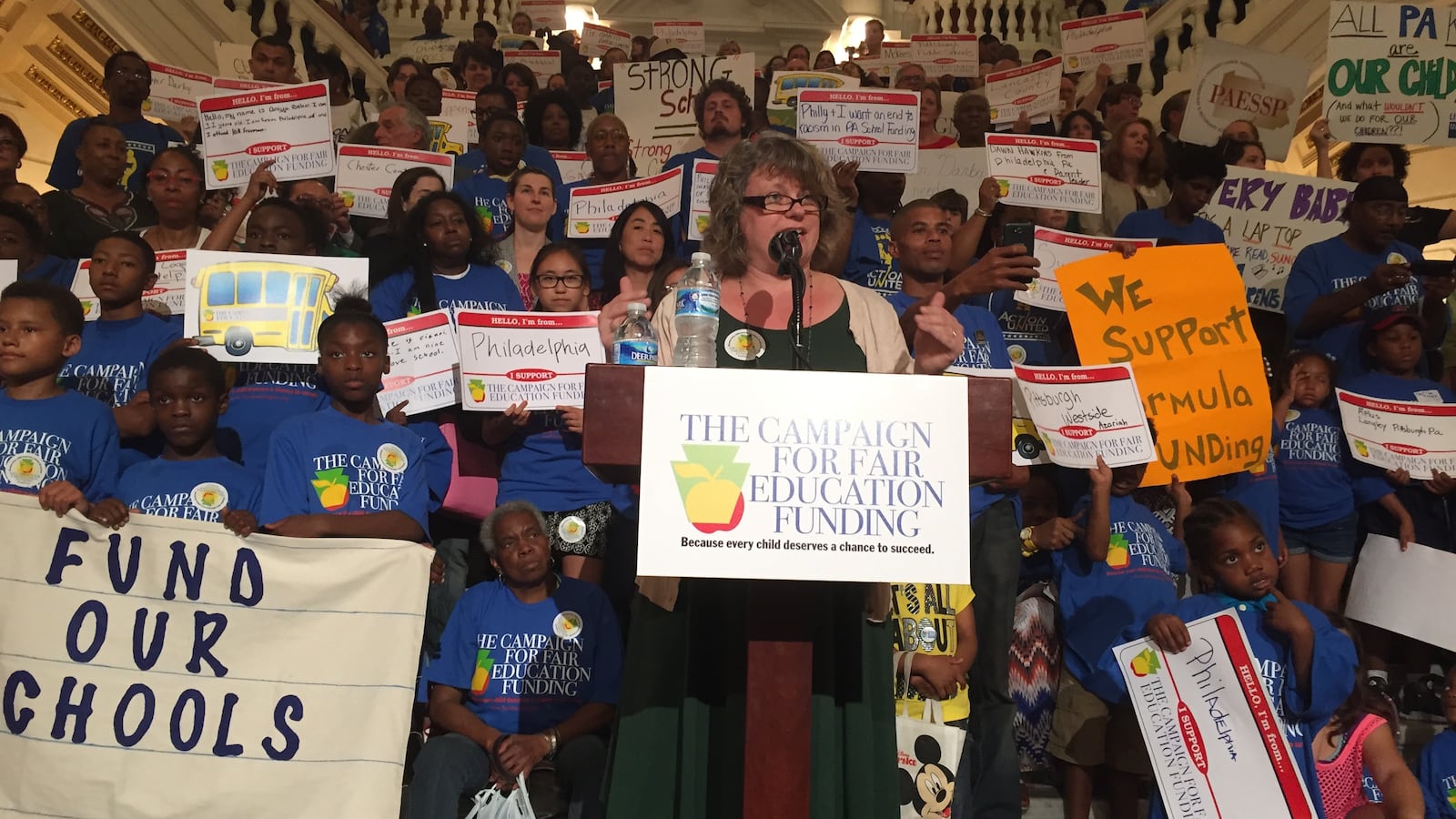

Hundreds of educators, leaders of faith-based groups, teachers, parents, and students convened Tuesday in the Rotunda of the Capitol to show their support for a fair funding formula for Pennsylvania’s schools. Supporters of all ages and from various school districts waved signs and chanted about the need to increase education funding.

The action was organized by the Campaign for Fair Education Funding, a coalition of advocacy groups from around the state. About 70 people traveled from Philadelphia with Public Citizens for Children & Youth (PCCY). Other groups came from as far away as Allegheny and Schuylkill Counties. About 400 protesters filled the Rotunda stairs.

The protest came after the long-awaited release of recommendations from the legislature’s Basic Education Funding Commission, which was charged with developing a formula to more equitably distribute state funding for schools. The committee’s proposal, which would “weight” aid to the 500 school districts based on demographic factors such as poverty, the number of English language learners, and the number of charters, has not yet been considered by the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

During the protests, members of the coalition also met with legislators to press for more education dollars and a fair distribution formula along the lines of the committee’s recommendations.

Beginning Saturday, members of the faith-based organization Philadelphians Organized to Witness, Empower and Rebuild (POWER), a part of the coalition, staged their own action, which they called a “Moral Takeover.” Members are occupying the steps of the Capitol and engaging in a 10-day fast to urge legislators to boost education spending beyond the $400 million increase that Gov. Wolf proposed in his budget.

The POWER activists spanned generations and locations. Sheila Armstrong was on the steps with five of her grandchildren, including 9-year-old Gianni Armstrong, who attends St. Rose of Lima Catholic School in Philadelphia. Three generations of the Armstrong family participated in the action.

“I’m here to represent the schools that are starving,” said Gianni.

The most senior Armstrong said that teachers’ being beholden to mandatory statewide testing was one of the most concerning parts of her children’s and grandchildren’s Philadelphia educations.

“But the nursing issue is something disturbing,” said Armstrong, referring to Philadelphia’s plans to outsource school nurses.

Her grandchildren have asthma, she said. Armstrong recalled how shaken she was by the death of Laporshia Massey, a Philadelphia 6th grader who died in 2013 after an asthma attack began in school when there was no nurse present.

POWER activists continued to occupy the front steps Tuesday; they also joined the coalition’s press conference.

“[Legislators] need to care more about the students and how they feel,” said Steel Valley High School sophomore Abbey Caspar. “Education is all about the students.” Steel Valley is in Allegheny County, near Pittsburgh.

Protesters were united across faiths, races, and hometowns. Opinions were echoed across advocacy groups.

“Now is the time to increase the state share of funding, so that all of our children, no matter where they come from, have the resources that they need and the resources they deserve to get a great start in life,” said Patrick Dowd, executive director of Allies for Children.

Jerry Oleksiak, vice president of the 180,000-member Pennsylvania State Education Association, said, “I know that Pennsylvanians like you are ready for a new direction — to put our schools back on track.

“But unfortunately not everyone in [the Capitol] is ready. There are elected officials in this building that think that years of cuts weren’t enough and they want to throw roadblocks up.”

According to the Education Law Center, Pennsylvania is one of three states that lack an established and predictable student-based education funding formula. The lack of a formula has led to economic disparities between wealthy and poor districts: The wealthiest schools receive 33 percent more funding than the poorest. Consequences of this inequitable funding are evident in districts like Philadelphia, where there are only 16 full-time librarians in a school district with 216 public schools.

“We need a fair funding formula so that students from any zip code in Pennsylvania have an equal opportunity to reach their full potential,” said Elizabeth Barr, an Altoona English teacher.

POWER is taking a more aggressive stance than the Campaign for Fair Education Funding as a whole: It is calling for $3.6 billion in additional funds to be budgeted for schools immediately, calling fair education funding a “moral issue.” The campaign supports Wolf’s plan to raise some taxes and increase education spending by $400 million, which restores severe cuts made to most districts since 2011 under former Gov. Tom Corbett. It wants to restore budget cuts and use a fair distribution formula, but it is calling for the increase to be phased in.

Principal Toni Damon of Dobbins Career & Technical Education High School in Philadelphia describes herself as a hands-on principal who gives her cell phone number out to her students. She says that she supports fair funding because it levels the playing field “for [her] children and other children across the state.”

“I’m sending my children to colleges in state and across the country,” she said. “I need them to feel comfortable with [new] technology. They can’t do that if [we’re] not given technology.”

She said career and technical education schools like Dobbins are operating with far too few resources and support staff, like nurses, given that their students are operating potentially dangerous tools like saws and other electrical equipment.

“Having machinery … should be some [kind of] consideration for having full-time nurses, with accidents that could take place.”

Funding as a moral issue

POWER is hoping to change legislative attitudes by casting education as a basic moral right and by using a tactic favored by religious leaders throughout history.

“[Fasting is] an ancient and sacred practice in many faith traditions. We’re in Ramadan and will have Muslims [fasting with us] on Friday. It calls attention to those who are in need because it tells you the experience of being in need,” said Margaret Ernst, communications coordinator for POWER.

“Without food in your belly, it takes twice as long to do what you need. For us, it’s a visceral reminder of what it’s like to educate kids with only half [or less] of the needed funding. We’re fasting because our schools are starving.”

Ernst said some legislators disagree about how morality should affect education funding.

Ernst said State Rep. Rick Saccone (R-Allegheny), who approached the group, said, “We can’t throw money at schools.”

Despite this disagreement, Saccone joined POWER in prayer.

“The moment was powerful. We were all praying to the same God, recognizing that moral leadership is necessary,” Ernst said.

POWER members have met with more than 50 legislators since March and have visited their offices daily during the fast. In April, they met with State Rep. Stephen Kinsey, who attended Germantown High School.

He said he doesn’t see funding as a moral issue either.

“Education is a constitutional right that every individual has the right to,” he said.

Kinsey applauded POWER’s tactics in drawing attention to their effort. But he said that he still thought that meeting with legislators was the best tactic for activists.

“The most effective way is to come and meet people," he said, "to put their faces [to who they are]. … Not to take anything away from POWER. When our government can tell a story about the importance of why we should support [a cause], we listen more intently. I can stand and say I’m a product of public education.”

While Kinsey spoke, members of POWER’s interfaith group remained on the steps. They sang and listened to speakers — one a Lutheran pastor from Lancaster who talked about how his own children went to well-off schools while his wife taught in a nearby district that is under-funded.

“Poverty is not exclusively found in urban places,” said the Rev. Matt Lenahan.

“In Lancaster County, we see a kind of microcosm of what’s happening around the whole state. This [funding] needs to happen in Lancaster, in Philadelphia, across the state.”

He spoke to a Baptist woman from Philadelphia who shared his frustration with inadequate school funding, as well as the unifying belief that faith was key for pushing for a fair budget.

“If we didn’t believe in [God], we certainly wouldn’t be able to continue. We believe in a God who provides manna in the wilderness,” said Lenahan.

Back inside the Capitol, State Rep. Harry Lewis of Chester County said that he (like Kinsey) was unaware of the protesters and didn’t want to comment on their action. He did say that he thought school superintendents play a big role in the funding issue, as they are the ones responsible for managing the money.

“We don’t want to keep putting money in and it goes to waste,” said Lewis, contending that physical education programs are especially to blame.

“Education is only about four basics, primary entities. First, the children. Second, the teachers. Third, the parents. These three components, with a couple of good leaders that help them manage, is what education is about. Everything else is fluff. All this stuff [school psychologists, counselors], we don’t need. It’s in [these three basics] where we’re really hurting,” Lewis said.

Samantha Weiss contributed reporting. Weiss and Michaela Ward are summer interns at the Notebook.