This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

For some students, school doesn’t come easily. They don’t revel in Shakespeare, nor do they thrive in the confines of the classroom. Instead, their brains whir with the goings-on of the street, their main concern protecting their vulnerable bodies.

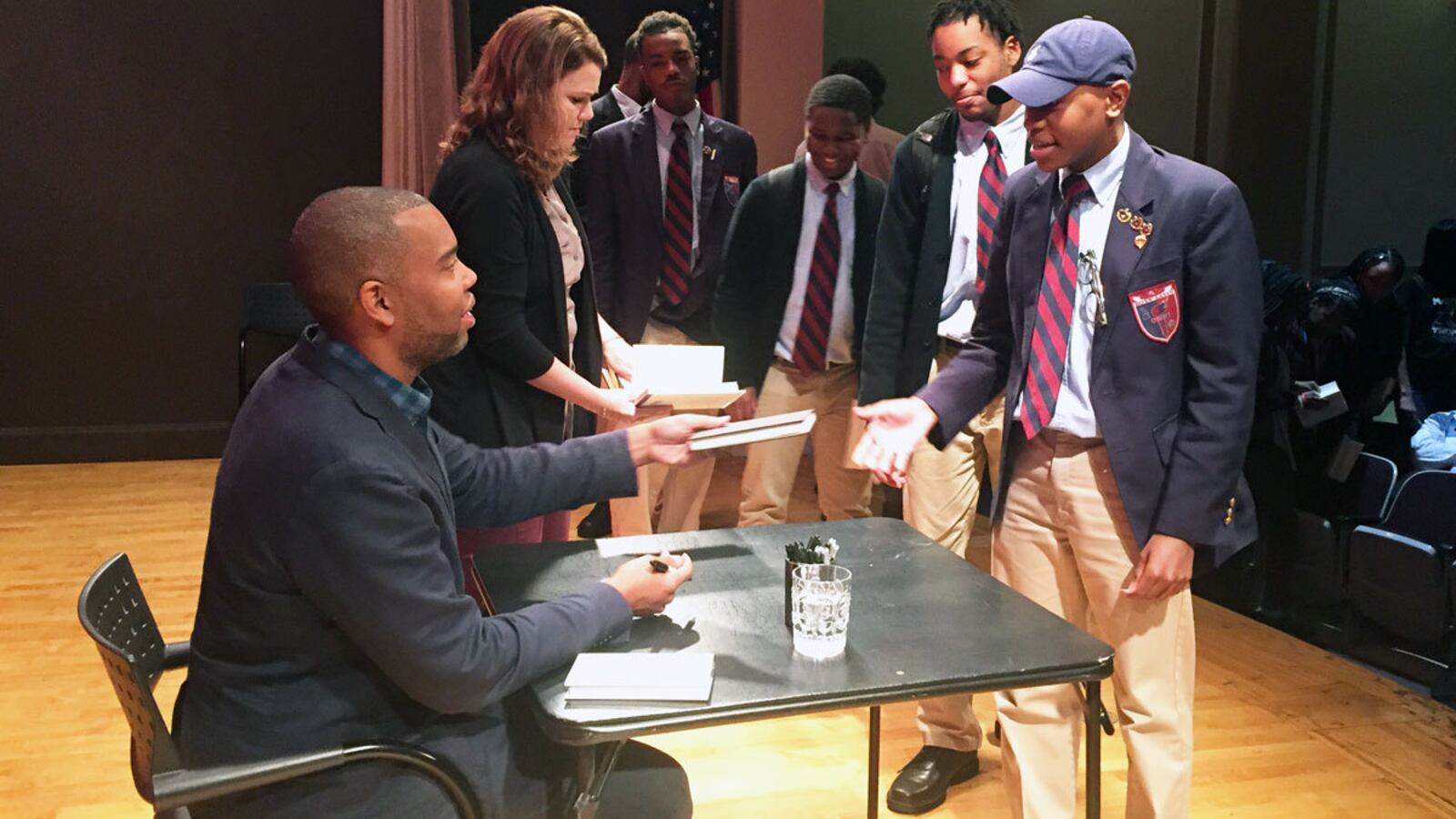

High school students across Philadelphia identified with this idea as they gathered at the Free Library on Friday to hear Ta-Nehisi Coates read from his latest book, Between the World and Me.

“This book was written for you. It is directed at my 15-year-old son, and he is in so many ways a stand-in for you,” said Coates, addressing the audience of 500 teens, students from 13 District and charter high schools. “My dad was born and raised in North Philadelphia, so my story in many ways begins here,” he added.

Coates’ book explores the reality of growing up Black in the United States, living in perpetual fear of violence under the pressure of an unattainable dream. The act of going to school is a risk; the very act of living in your body while Black is a gamble. The deaths of Michael Brown Jr., 18, Tamir Rice, 12, and Sandra Bland, 28, he says, are verifications of this predicament.

“The events that are taking place right now, the racial injustice impacts me,” said Fatme Chaloub, 16, a Girls’ High student who attended. Chaloub aspires to be a cardiologist. “I feel like once they find out you’re Black, they make assumptions,” she said.

Students at the event all received a copy of the book through the Free Library’s Teen Author Series and have worked their way through the text in extracurricular book clubs and English classes.

“This one has truly impacted the kids,” said Kathleen DiTanna, who read the book this month with students in her AP Language and Composition course at Girls’ High. “They are painfully aware of what’s been happening. [Each time someone died at the hands of the police,] they took it like it was their brother. It’s like some of them have PTSD.”

In Philadelphia, movements such as “Philadelphia is Baltimore” connected the city to the case of Freddie Gray, who died after suffering a spinal injury in a Baltimore police van. The group brought attention to Philadelphia’s own Brandon Tate-Brown, who was shot and killed by Philadelphia police in December 2014.

District Attorney Seth Williams declined to charge the officers.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s 2015 report, "An Assessment of Deadly Force in the Philadelphia Police Department," revealed that Philadelphia, with a majority White male police force, averaged 49 officer-involved shootings a year from 2007 to 2014. Blacks, who make up almost half the city’s population, accounted for 81 percent of the suspects shot.

Coates recounted these facts plainly for the young audience.

“There was some decision made long ago in the deep, deep past [in which] folks decided that some group of people who looked like me would have to get up in the morning every day and worry about their safety. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the people who lived in the country, who looked very different, would not have to worry about that,” he said.

Students anxiously searched the pages of the text for solutions or for some literary catharsis. During the question-and-answer session, a student from Bodine High School asked, “In your book, there was a lack of hope in the future for Black people in terms of safety and cultural revitalization. So was that a conscious choice of yours to not pander toward an idealized future, or was it something that came along while you were contemplating?”

This was Coates’ response:

What I wanted to do in the book was decouple two notions: the notion of hope and the notion of responsibility to resist. What I wanted to get to my son is, even if we feel like there’s no hope, even if we feel nothing will change in our lifetime, you have a responsibility to resist. You have a responsibility to struggle. That is your hope right there. Your only hope is the right to struggle. And that’s not a small thing. Hope is the right to live and die honorably. That’s what struggle gives you. I can’t control what the world does. Should the world end one day, should the world go over the cliff, when the calculus is made, I want to be known as one of the people trying to prevent the world from going over the cliff, not one of the people trying to push the world over the cliff. And if I can do that, that’s a good life. That’s the hope I have to offer.

Students have already been working around this feeling of hopelessness. Increasingly, in Philadelphia, they are resisting, through activism and by recording their own thoughts on and experiences with social injustice.

“Reading this book and being here today to hear him speak is a follow-up to the Black Lives Matter movement for me,” said Anaiia McLean, an 11th grader at YESPhilly charter school. “I’ve done work at the Attic Youth Center and I’m looking for other ways to get involved.”

In response to Coates’ work, McLean has written poems about what it’s like to live in a Black body and grow up in South Philadelphia.

In their English class with teacher Joshua Block, juniors at Science Leadership Academy reflected on Between the World and Me with letters to Coates. Kayla Cassumba connected the book with the purpose of schooling. Aissatou Bah explained her everyday fear as a Black teen in Philadelphia, while Felix Schafroth Doty checked his White male privilege. Matthew Willson expressed astonishment at what his Black peers have endured.

Some questioned whether they can ever be free of the burden of race. Others offered meaningful critiques of Coates’ rejection of the American dream.

For Eva Karlen, the book is a lesson in agency.

“Between the World and Me has helped to show me the importance of ownership of one’s reality.”