This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Your browser does not support the audio tag.

When he was 35, Quaris Carter arrived in North Philadelphia as a stranger to the East Coast, carrying two garbage bags of clothes and barely a dime.

After more than three decades in Texas, he was just grateful for the chance to redefine his life.

"I actually sort of saw myself change," he said. "I started feeling free, like, I’m going somewhere new. It’s a new start."

This was July 2010.

The story of how he got there and, within four years, graduated from Community College of Philadelphia is a tale of American reinvention, one that begins in Houston’s drug-riddled Fifth Ward neighborhood at the height of the 1980s crack epidemic.

The son of a devout Southern Baptist single mother, Carter says he was a good student for a while, but the pressures of the neighborhood overcame him.

"Everyone was telling me to get money. And I figured getting money was the only way out," he said.

"My mom never knew I sold crack until about a year ago. She never caught me, she never seen me with money. Well, the money she actually got off me when she searched me when I came home. I told her I was shooting dice. She was like, ‘Don’t be shootin’ dice, but as long as you’re not selling drugs …’"

At 12, already drinking and smoking weed, he made $500 a week dealing crack after school, often selling to adults who were more than twice his age.

"We had older guys, like five, six years older, who told us first off, ‘Don’t do it.’ Then they were like, ‘This is how you do it,’" he recalled. "So it wasn’t structured like we had a boss or an underboss or gang leader. It wasn’t like that. It was just like common respect. Be nice to the elderly. Don’t disrespect no moms or grandparents or anything like that."

In high school, though, Carter quit selling and convinced himself to focus on school. This sort of pivot has become a recurring theme in his life: Every time he bends toward the darkness, something inside pushes him to keep striving toward the light.

And so, for a while, he was a quintessential Texas high-schooler. The linebacker-sized teen joined the football team and earned cash by mowing lawns and washing cars.

But that phase, too, did not last.

Code of the street

Now, 20-some years later in Philadelphia, Carter, 38, lives in a $350-a-month rooming house on a dilapidated corner of Diamond Street in North Philly.

To afford the application fee for community college, he had to sell his plasma at a blood bank

At community college, two of his sociology professors saw potential and took an interest. They urged him to ride the 23 SEPTA bus from Center City to Chestnut Hill. The bus sputters past the full swath of city life, from downtrodden storefronts and vacant lots to million-dollar homes on the city’s edge.

"They just start telling me you got to start building social and cultural capital," he explained. "You need to start getting out and meeting different people in different social classes, and they can show you how beautiful life is."

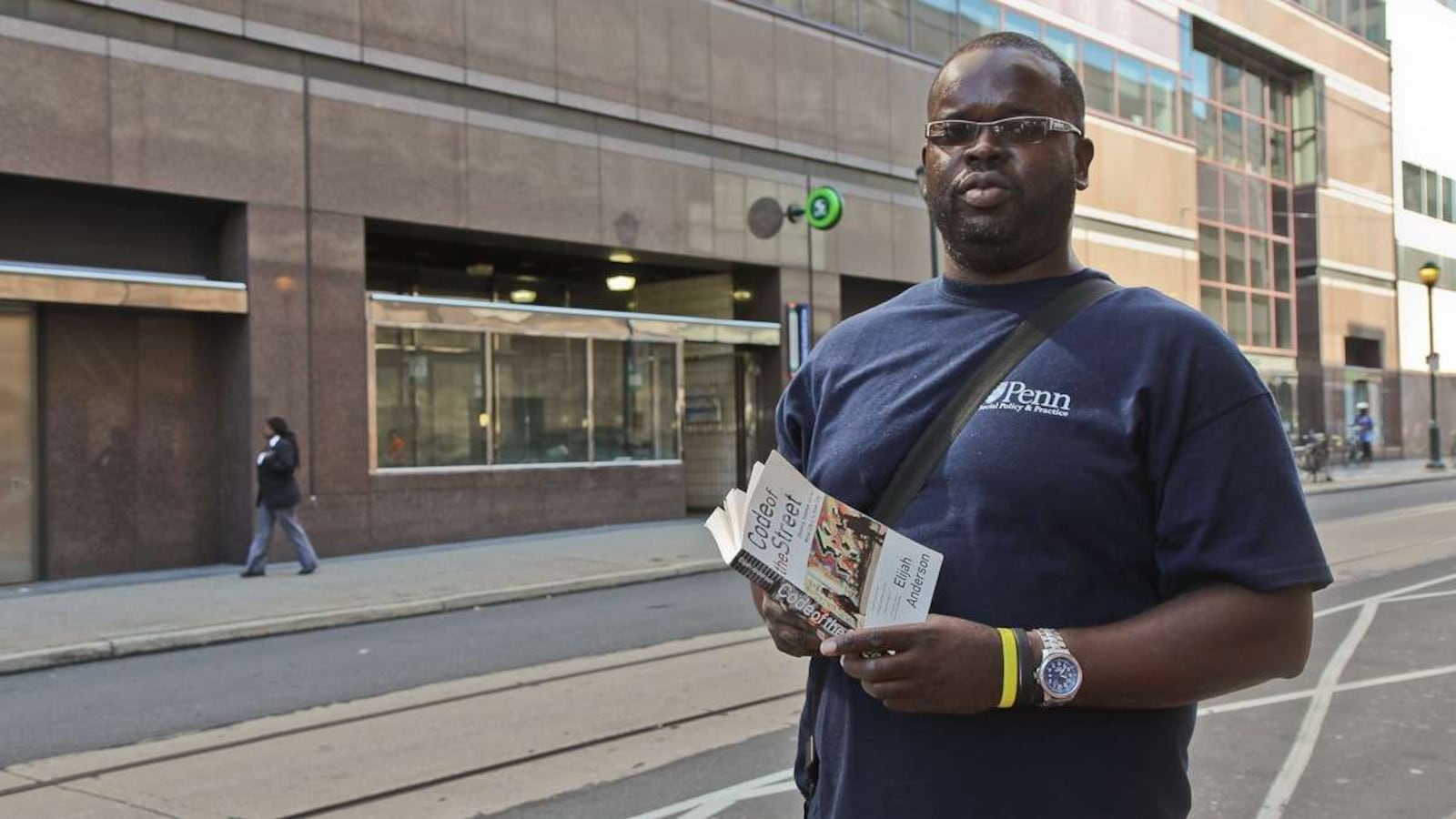

The assignment was inspired by sociologist Elijah Anderson’s 1999 book, "Code of the Street," an acclaimed cultural analysis of life along Germantown Avenue.

On a recent Friday, Carter retraced that journey, meditating on the mistakes of his past as he peered through the scuffs on the big bus window at the changing urban terrain.

At the intersection of Germantown and Indiana Avenues, Carter said that after graduating high school, he went to the University of Houston.

"I was doing well, but I had no family support," he said. "They were telling me, like, college is good, but you need to go get a job to help pay some bills and things like that. So I just stopped going to school."

He started looking for work, even thought about the Navy, but soon became discouraged that his life wasn’t taking the shape that he had hoped.

"After that, I just started committing crimes," he said.

Some guys he knew from the neighborhood had been robbing jewelry stores at gunpoint, and they convinced Carter to join them.

Compared to the strictures of his Baptist upbringing, crime had its appeal.

"They wasn’t telling me that I had to wait to die to have a better life. They was like, ‘Look, you can have a better life right now. Don’t be lazy. Let’s go get this money,’" he recalled.

"So I was like, ‘cool.’ And I knew I was smarter than them, so I just, I guess back then, just applied myself."

‘Never shoot anyone’

If a store opened at 9, Carter and his crew would show up at 9:02 with ski masks and automatic weapons.

"I had a policy … Never shoot anyone. Don’t shoot anyone. They’re going to give it to you, like, it’s not theirs. Don’t shoot ’em. If you shoot them, somebody going to shoot you," he said. "You know these are people coming to work. … We’re going to get what we want to get and we’re gonna leave. It’s simple as that."

They robbed stores in the Houston area for three months. Carter had a connection who would pay him $10,000 to $15,000 for each duffel bag full of jewelry.

"I was like, ‘This is stupid, but it’s money,’" he said. "And as long as I have money, I knew that people would – not respect me, I knew they wouldn’t respect me – but … like me."