This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Facing a $300 million structural deficit and still uncertain whether it will get the increased revenue and labor concessions it is seeking, the School District is asking schools to prepare to operate next year with a principal and a bare-bones allotment of teachers – and just about nothing else.

That means the contractual maximum class size in every classroom – 33 students in grades 4-12 and 30 in K-3. It means no dedicated money for guidance counselors, interscholastic sports, extracurricular activities, librarians, art or music.

No money, even, for secretaries.

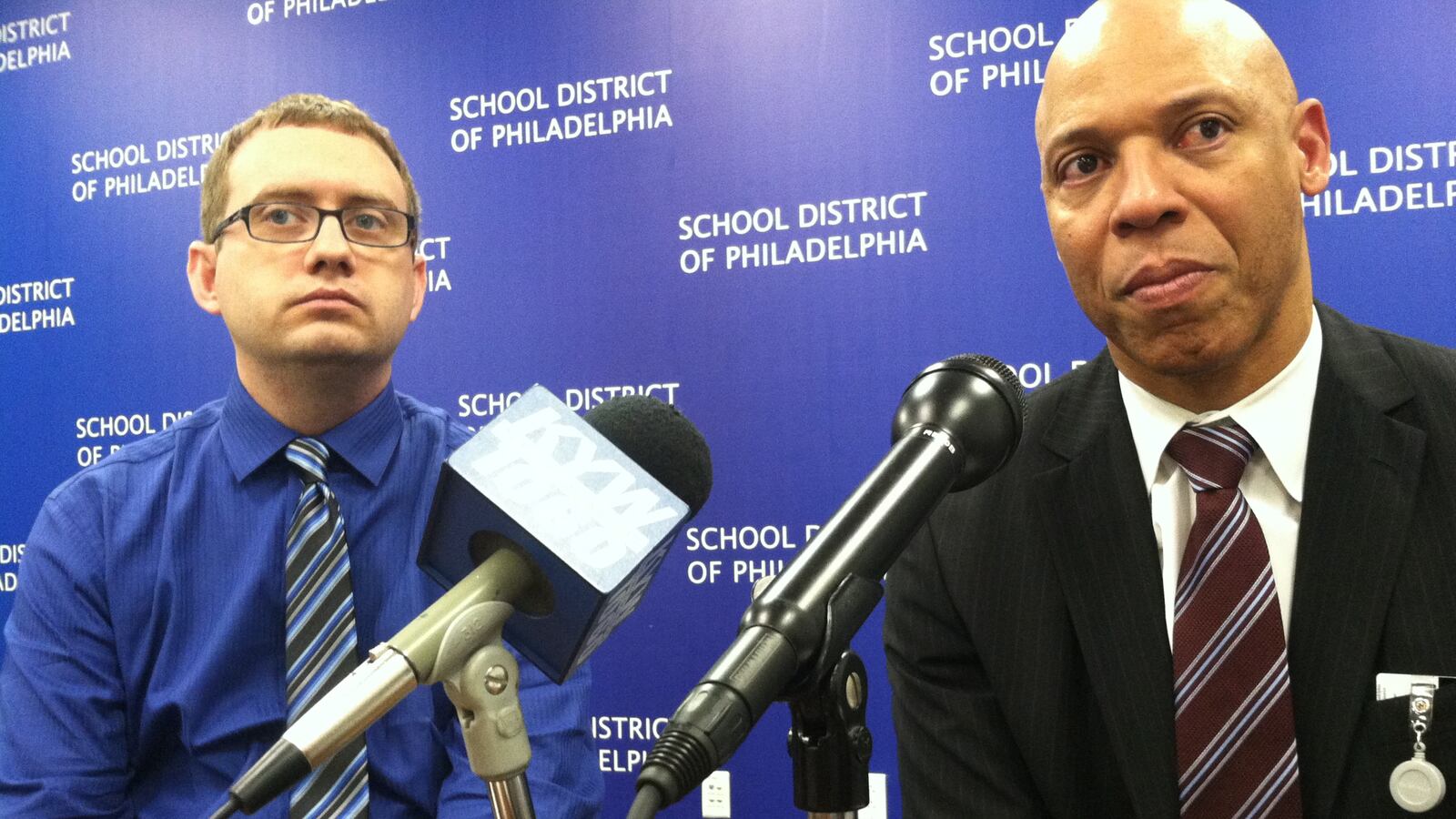

“We can’t afford anything else,” said Superintendent William Hite in presenting the doomsday scenario at a press briefing Thursday afternoon, just before he went to tell his principals the grim news via webcast.

District Chief Financial Officer Matthew Stanski presented the budget to the School Reform Commission at its meeting Thursday night.

The school budgets that principals will get Friday are effectively reduced by $220 million, 22 to 25 percent from their already austere levels. It will stay that way unless the District gets the $120 million in additional revenue it is seeking from the state, $60 million from the city, and $133 million in concessions — about 10 percent in wage and benefit costs — from the teachers’ union.

“This situation is dire, it’s real, and it’s why we’re required to ask for sacrifices from all parties,” Hite said. The District’s blue-collar union last year agreed to about 10 percent in wage and benefit concessions.

The District has begun negotiations with the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, whose contract expires at the end of August.

For the union, it could come down to a tradeoff between the salary and benefit concessions and what Hite described as “massive” layoffs. The class-size maximums specified in the contract are generally much higher than the norm in most suburban districts. Many principals were able to use discretionary funds to reduce class size in their schools below the contracted maximum, but will not have the discretionary funds to do that now.

But to maintain the relatively high class-size maximums mandated in the contract, Hite said, “requires us to eliminate some of the other things” — sports, libraries, music — considered essential in most school districts.

Hite did make it clear that even if the District gets what it wants in money and concessions, it will not be enough to give students a "quality" education.

"That is just to eliminate a deficit … even with the $304 million … we still need additional resources to actually provide students with what I believe would be a quality educational experience," he said. "I want to see art and music in every school, I want to see language in the elementaries, I want to see career and technical education programming for our high school students.”

Down to what’s mandated

But without the additional revenue and the labor concessions, schools are down to barely being able to fulfill state and contractual mandates, along with a few non-mandated services including kindergarten and school security that the District believes are indispensable.

The budget would maintain the current level of school police, but would reduce nursing services, which were already slashed, from one nurse for every 1,000 students to one for every 1,500. It will continue to fund special education and services for non-English speakers, Hite said.

UPDATE: In addition to the school-based cuts, the District’s budget reduces an already decimated central office by $23 million. Central office had about 800 positions in 2011 and is now around 450. It is still unknown how many more jobs will be lost, but ultimately central office will account for only 2 percent of the operating budget — “unheard of for a district the size of ours,” Hite said.

That makes it hard to provide basic functions. The charter office, which oversees 84 charter schools, has only three people, for instance.

The budget, he said, “is grounded in reality and based on the revenue we know we have. Too many budgets and contracts in the past had been based on what we had hoped for and not necessarily what was real.”

The huge budget hole is the product of a two-year-long crisis primarily brought about by sharp drops in state and federal aid. There was the end of the federal stimulus and decisions in Harrisburg to reduce the basic education subsidy and eliminate such big-ticket line items like reimbursement for charter costs, all of which meant that Philadelphia saw a more than $200 million reduction in revenue at a time when fixed costs were rising.

Last year, the District borrowed $300 million to make ends meet, but it has exhausted its borrowing power and doesn’t want to do that again in any case.

“To continue to borrow is to continue to put the District on a path to bankruptcy,” Hite said.

The structural deficit — the amount where expenses exceed revenues — is $304 million, but the District expects to end this fiscal year with a reserve that it will use to reduce the actual shortfall to $242 million.

Hite said that the District’s options for reductions are limited. Hite said that in its $2.5 billion budget, about $1 billion is mandated and nondiscretionary — the costs it must pay to charter schools, $729 million, and its debt service, $280 million.

At the same time, it is facing increases in fixed costs. For instance, the state is requiring that contributions to the teachers’ retirement fund will go from 12 to 16 percent of teacher salaries.

Mayor Nutter is working to raise the $60 million asked of the city and to raise the money from Harrisburg, which has so far been cool to noncommittal on the District’s request.

Hite is hopeful that Harrisburg, historically hostile to requests from Philadelphia, is taking the request seriously.

“Individuals are listening,” he said, but are also reiterating that the commonwealth has its own budget challenges.

At the SRC meeting, Hite asked everyone in the room to “plead” for the additional revenue.

After listening to Stanski’s presentation, Commissioner Feather Houstoun said: “We need all the help we can get.”