This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

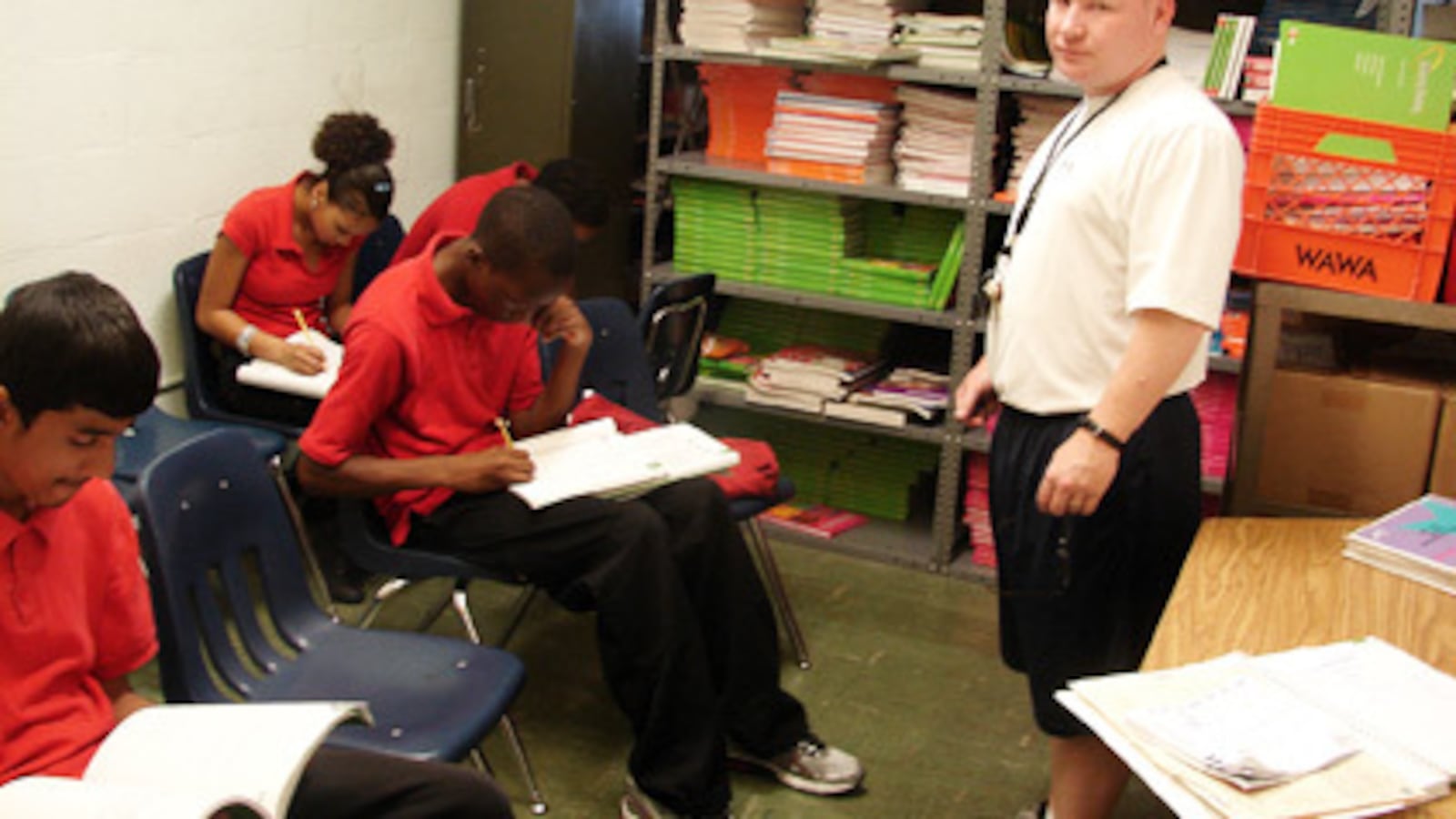

Bernie Rogers spends 45 minutes each day teaching inside a cramped storage closet.

Packed shoulder to shoulder, up to eight children sit in plastic chairs and hold their books and papers in their laps. Rogers stands almost directly on top of them while he conducts his supplemental reading lesson.

Though Rogers and his students barely have room to move, he said the arrangement has its benefits.

“We’re so close, there’s no room for them to fool around,” Rogers explained.

In the jam-packed public schools of Northeast Philadelphia, which have undergone a demographic sea change over the past two decades, such scenes are common.

Rogers’ school, Gilbert Spruance Elementary, currently enrolls 1,322 students – almost 500 students more than the building’s official maximum capacity. In District parlance, that means a “utilization rate” of 158 percent, nearly double the ideal rate of 85 percent.

As a result of the overcrowding, Spruance has no classroom space available when small groups of students need to be pulled out of their regular classes. So Rogers and his colleagues teach wherever they can: The ends of hallways. The faculty lounge. And yes, even in closets.

“Anywhere there’s space,” said Michelle Diamond, a special education teacher who is one of two teachers’ union building representatives at the school.

That could be the motto of dozens of Northeast schools. Unlike the rest of the city, where the School District counts 70,000 “empty seats” and dozens of half-empty schools, the Northeast copes with serious overcrowding.

According to a recent District report, 20 of the 45 schools in the region operate beyond 100 percent capacity. Another 16 are also considered overcrowded because they are above 85 percent utilization. All told, the District says that 94 percent of the 42,821 available classroom seats in the Northeast are filled.

“We’re bursting at the seams,” Arthurea Smith told officials at a May 10 community meeting. Smith is the principal of Farrell Elementary, which is at 122 percent of capacity.

But even as the District undertakes a comprehensive new “facilities master plan,” it is uncertain how much relief it can provide to the Northeast. There is little money for new construction. Because so many schools in the region have the same problem, less expensive options are limited. And officials are likely to have their hands full with plans to close up to 50 school buildings in other parts of the city.

A full list of proposed facilities changes will be unveiled in October, but the District has given residents of the Northeast little reason to hope.

“I get that there’s urgency,” District Deputy for Strategic Initiatives Danielle Floyd told the May 10 gathering.

“But this area [of the city] is going to be very challenging.”

A city within a city

Overcrowded schools in the Northeast are nothing new. And because of the demographics of the area, the problem is not likely to go away any time soon.

The School District defines its “Northeast meeting area” as the region bounded by Tacony-Frankford Creek on the south, the Delaware River on the east, Bucks County on the north, and Montgomery County on the west. That area includes neighborhoods in the so-called “Lower Northeast,” such as Frankford and Mayfair, as well those in the “Far Northeast,” like Torresdale and Fox Chase.

Altogether, the region is now home to almost 425,000 people – more than live in the entire cities of Oakland, Calif. or Cleveland, Ohio.

Over the last twenty years, the Northeast has seen “remarkable racial and ethnic change,” said Larry Eichel, project director for the Philadelphia Research Initiative (PRI) at the Pew Charitable Trusts. Once almost entirely White, it is now a hodgepodge of different ethnicities and cultures.

According to a recent study by PRI, the Northeast has lost one-third of its White residents since 1990. But during that same period, the region’s overall population has grown by 5 percent, primarily because of big increases in Hispanic and Asian residents.

“The Northeast used to be seen as a very separate place,” said Eichel. “But now, it’s becoming a lot more like the rest of the city.”

The dramatic diversification is evident in the community served by Spruance Elementary, a triangular Lower Northeast neighborhood of roughly 30 square blocks bounded by Roosevelt Boulevard, Castor Avenue, and Knorr Street.

In 1990, this area had just 22 non-Latino Black residents. Now, it has 3,814, according to an analysis conducted for the Notebook by Michelle Schmitt, the project coordinator for Temple University’s Metropolitan Philadelphia Indicators Project.

That’s an astonishing 17,236 percent increase.

During the same period, the neighborhood’s Latino population has grown by 647 percent, and its Asian population by 325 percent. In addition, an estimated 38 percent of neighborhood residents are foreign-born, up from 15 percent in 1990. And an estimated 86 percent of children in the neighborhood attend public schools, up from 65 percent in 1990.

“This is an extraordinary example of neighborhood change,” said Schmitt.

Spruance’s changing student body has reflected this transformation.

According to School District data, Spruance’s White population has declined 62 percent since 2001-02. Over the same time period, the school’s African-American population has grown 45 percent and its Latino population has grown 34 percent.

“We’re very proud of our diverse population,” said Spruance principal Betty Klear, noting that the school has four bilingual counseling assistants and a mural painted several years ago to celebrate the changing student body.

‘If you build it, they will come’

The pressure on student enrollment in the Northeast is not expected to let up anytime soon. Based on projections prepared by outside consultants, the District is planning for continued population growth and increasing diversity in the area.

For the students and staff at Spruance, that will likely mean a continued need for creative use of space.

Closets will likely still be used for small group instruction. Wheelchairs and other equipment for Spruance’s students with multiple disabilities will likely still have to be “stored” in the hallway. And crowded classrooms – often with more students than would otherwise be contractually allowed – will likely still be led by “co-teachers” who share both responsibility and space.

“You work with what you have,” said Klear, stressing that overcrowding is no excuse for poor academic achievement.

Indeed, last year Spruance met its Adequate Yearly Progress targets under No Child Left Behind. More than 52 percent of students scored proficient in reading on the PSSA and 62 percent in math. About a third of the school’s 8th grade graduates went on to special admission high schools, said Klear.

Klear said the school’s solid performance has contributed to its high enrollment.

“Parents want their children in places perceived as good schools, and schools here have a good reputation,” she explained.

For years, students from other parts of the city were bused to the Northeast via the District’s desegregation program. As recently as 2001-02, ,more than 10,000 students of color were transported from their home neighborhoods to otherwise predominantly White Northeast schools, including Spruance.

That effort has been scaled back dramatically, however. Now, Spruance’s racial diversity comes from the new families who have moved into its catchment area.

District officials said they have been trying to keep pace with the swelling demand.

Seven of the 14 “Primary Education Centers” the District has built since 1997 are in the Northeast, including one opened at Spruance in 2001. That facility now holds 12 K-2 classrooms.

An addition was built onto Franklin Elementary in 2002, while Lawton and Ziegler were expanded in 2008. Both Lincoln and Fels High Schools were replaced in 2009.

“Not every school has been touched, but we’ve made a lot of investment,” said the District’s Floyd, who is in charge of the facilities planning process.

Moving forward, said Floyd, options include building more additions and redrawing boundary lines. But these only work if there is room on school grounds and the neighboring school is not also overcrowded.

“We don’t want to just shift the problem to the school next door,” said Floyd.

A more likely move for the District could be to change schools’ grade configurations. Overcrowded K-8 schools like Spruance and Mayfair, for example, could be converted to K-5 schools. A new middle school option would have to be created, but Superintendent Arlene Ackerman has signaled that the new facilities plan will prioritize a return to “traditional” middle schools serving grades 6-8.

But even this type of move could prove controversial.

“A lot of families love the K-8 model,” acknowledged Floyd. “We’re trying to find a balance.”

In the end, the best solution to overcrowding in the Northeast might be the most difficult of all: significantly improving the quality of schools in other parts of the city, which could ease the influx of school-age children to the region. But as things stand, said Klear, the demand at Northeast schools will likely overwhelm whatever strategies the District might pursue.

“What’s the line in that baseball movie?” Klear asked, referring to the film Field of Dreams. “‘If you build it, they will come?’ That’s pretty much the way it is up here.”

Editor’s note: Michelle Schmitt of the Metropolitan Philadelphia Indicators Project is the author’s wife.

This story is a product of a reporting partnership on the facilities master plan between the Notebook and PlanPhilly.